Arabs and Africa: Trade, Conquest, and the Founding of a New African Order!

Arabs and Africa

Trade, Conquest, and the Founding of a New African Order!

Introduction

Winds of Trade and Wars of Formation

Long before Africa was reduced to the rigid lines of European colonial maps, it existed as a fluid and interconnected continent. It had hummed with activity for centuries, shaped in large by Arab movement through trade and conquest across the sea and the desert. Along the eastern shore, the steady rhythm of the Indian Ocean was met by the creak of wooden hulls and the pull of lateen sails as dhows made their approach from across the sea. At the same time, under the relentless Saharan sun, long lines of camels moved slowly across the dunes, their bells marking the passage of caravans through vast expanses of sand. These movements did not follow a single logic. Some were driven by exchange and seasonal commerce, while others were driven by conquest, settlement, and the consolidation of political authority.[1]

This is the story of Arabs in Africa and their enduring legacy, and of how Arab political, commercial, and cultural formations shaped and sustained the African world long before the arrival of European powers. While in North Africa, Arab armies established new political orders through conquest and administration, in East Africa Arab merchants embedded themselves gradually within existing coastal societies through trade, intermarriage, and religious exchange. From these coastal landings and desert crossings, cities rose at the ocean’s edge and along the desert frontier as new languages and forms of worship took root.

This study traces how Arab conquest and state formation in North Africa and commerce and settlement in East Africa unfolded in parallel, often contemporaneously, shaping different but interconnected routes into the African interior. It moves from mechanisms of entry to the systems that were built and sustained, systems later relied upon by European colonial powers—and finally to the enduring marks Arabs left behind, marks that continue to shape the continent’s political, economic, and cultural landscapes today. It is a history of Arab influence and how it became deeply embedded across the continent.

Chapter 1

Pathways into Africa – Conquest, Commerce, and Settlement

1. The First Footprints and the March Inland

From the outset, Arab engagement with Africa followed multiple pathways, a contrast that frames a twin trajectory, that is, conquest in the north and commerce in the east. These two broad modes of expansion shaped this early encounter: in North Africa, a conquest‑driven process rooted in military advance, settlement, and the consolidation of political authority and in East Africa, a trade‑driven process that unfolded gradually along the Indian Ocean coast through seasonal commerce, social integration, and urban growth.[2] Together, these contrasting pathways frame the subsections that follow.

1.1. The Arab Conqueror – A North Africa Case Study

The first sustained Arab incursion into North Africa occurred in the mid‑seventh century CE, following earlier limited raids in the early seventh century that failed to secure permanent control, when Arab armies moved westward from Arabia into Byzantine‑controlled Egypt.

Under the command of ʿAmr ibn al‑ʿĀṣ, Muslim forces entered Egypt in 639 CE, capturing the Babylon Fortress and, by 642 CE, securing Alexandria.[3] Egypt, having fallen into the hands of Arab raiders, was incorporated into the Rashidun Caliphate, the first Islamic polity (632–661 CE) governed by the immediate successors of the Prophet Muhammad.[4] Fustat was founded soon after as a new Muslim garrison city near Alexandria. It became Egypt’s first Islamic administrative capital and marked the transition from temporary military occupation to permanent settlement and state administration. Fustat corresponds to the area now known as Old Cairo within the modern city of Cairo. Egypt thus became the initial base from which Arab power, population, and administration radiated westward across North Africa and toward the Saharan interior.

From Egypt, Arab forces advanced westward along the Mediterranean littoral into Cyrenaica and Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia). A major expedition in 647 CE, led by ʿAbdallāh ibn Saʿd ibn Abī Sarḥ defeated Byzantine forces and imposed compulsory fiscal tribute on defeated local authorities in recognition of Muslim political supremacy, without yet establishing full administrative control, signalling a shift from frontier raiding to sustained territorial expansion.[5] This momentum culminated in 670 CE with the founding of Kairouan by the general Uqba ibn Nāfiʿ. Established deep inland from the coast, Kairouan functioned as a permanent military and administrative center, anchoring Arab settlement and serving as the primary base for further campaigns across North Africa.[6]

By the late seventh century, conquest gave way to consolidation. The fall of Carthage in 698 CE under Ḥassān ibn al‑Nuʿmān effectively ended Byzantine political authority in North Africa. Carthage had been the principal Byzantine administrative and naval center in the western Mediterranean, and its loss removed the last major imperial stronghold capable of resisting Arab advance, clearing the way for Arab governance to take root across Ifriqiya.[7] In the decades that followed, Arab administrators extended systems of taxation, law, and governance, while Arabic and Islam spread through a combination of state structures, migration, and local conversion. These developments transformed Arab rule from a military presence into a settled and enduring social order by the late seventh and early eighth centuries.[8]

Expansion continued westward into the central and western Maghreb during the late seventh and early eighth centuries, most notably under the leadership of Mūsā ibn Nuṣayr. Through a combination of military campaigns, negotiated alliances, and incorporation of Berber groups into the Islamic polity, Arab authority was stabilized across much of the Maghreb al‑Aqṣā (modern Morocco). Therefore, by the early eighth century, Arab settlement and administration had become firmly established across North Africa, leading to societies in which Arab and Berber populations were increasingly intertwined.[9]

Although large‑scale conquest halted at the southern edge of the Sahara, the settlements and political structures established in North Africa enabled a new phase of inland engagement. From the eighth century onward, trans‑Saharan routes linking North Africa to the Sahel were revived and expanded, facilitating the movement of goods, people, and religious ideas toward regions such as Gao, in present-day Mali, and Kanem, centered in the Lake Chad basin of what is now Chad and northeastern Nigeria.[10] In this way, the Arab conqueror’s pathway beginning with military conquest and culminating in settled rule created the foundations for sustained inland penetration, distinct in origin yet comparable in outcome to the trade‑driven expansion unfolding along Africa’s eastern coast.

1.2. The Arab Trader – An East Africa Case Study

Following the Monsoon’s Breath

While Arab armies were consolidating power across North Africa in the seventh century, a parallel and largely contemporaneous process was unfolding along Africa’s eastern seaboard, driven not by conquest but by commerce.

Arab traders were central to transforming existing patterns of mobility and exchange into organized, sustained routes that linked Africa’s coasts to its interior.[11] Their engagement unfolded gradually: beginning with early maritime contact along the Indian Ocean coast from the seventh century,[12] consolidating through settlement and commercial organization, and later extending inland through overland routes and institutional networks. Over time, seasonal trade became permanent exchange, coastal interaction developed into structured systems, and movement across sea and desert enabled the spread of commerce, belief, and influence deep into Africa’s interior.

1.2.1. The Singing Dhows: Sailing the Ocean Highways

At the heart of these maritime routes was the dhow, a distinctive sailing vessel used across the Indian Ocean. Its hull, built from resilient teak or coconut wood, was shaped for durability and long-distance travel rather than ornament. Above it, a large, triangular lateen sail was rigged to harness prevailing monsoon winds for long-distance navigation.

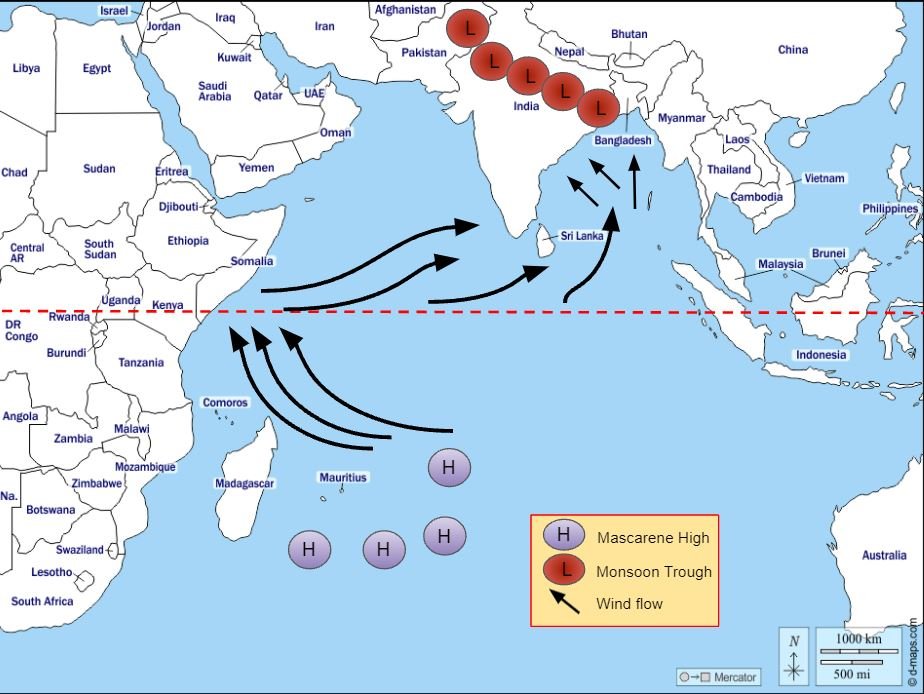

This vessel was central to a maritime system that shaped Indian Ocean trade for centuries, operating in direct relation to predictable seasonal monsoon wind patterns. For six months of the year, from December to March, these winds blew steadily from the northeast across the Indian Ocean basin, funneling down from the Arabian Peninsula.[13] An Arab trader operating from ports in Oman, southern Arabia, or the Persian Gulf, seeking African ivory or gold or other African merchandise, would wait for this seasonal shift. Catching the northeast monsoon, his dhow could sail southward to the Swahili Coast in a matter of weeks, carried by a predictable and powerful natural force.[14]

A historical map of the Indian Ocean monsoon wind patterns, with arrows showing the seasonal directions. Source: British Museum digital collection.

Trade was followed by a period of another enforced waiting, during which merchants remained at the African ports until the seasonal reversal of the monsoon winds made return voyages possible. From April to September, the monsoon reversed direction, now blowing reliably from the southwest. With his hold filled with African goods, the trader would raise his sail once more and allow this returning wind to carry him home.

This dependable rhythm rendered the Indian Ocean a regularly navigated, wind-driven corridor of long-distance trade. Ports such as Kilwa, Mombasa, and Zanzibar grew from modest coastal settlements into wealthy stone cities, not solely because of local political dynamics, but because they occupied ideal stopping points along this immense maritime corridor linking Africa to Arabia, Persia, and beyond.[15]

There are no clear or precise dates that can be traced for when contact between Africa and the Arab trading world was first established; instead, the relationship emerged through successive waves of interaction, expanding from tentative coastal landings into deeper and more sustained forms of commercial engagement.[16]

By the seventh century CE, Arab merchants were making seasonal voyages down the East African coast, moving within long-established Indian Ocean exchange systems and drawn by commercial incentives such as ivory, mangrove timber, and other high‑value coastal goods carried through monsoon-linked trade routes.[17] These voyages were likely small-scale, driven by demand in the arid Arabian Peninsula for African produce. When they reached the African coast, they found a coastline dotted with Bantu-speaking fishing and farming communities. Archaeological evidence such as early Muslim coinage and pottery shards recovered at sites such as Shanga in Kenya indicates regular contact and a sustained Muslim presence by the 8th century, without yet implying permanent settlement.[18] These traders were by then only visitors, not settlers, their presence dictated entirely by the monsoon cycle.

As profits grew—driven by rising trade volumes, a widening range of commodities, and increasingly reliable coastal provisioning—so did permanence come about.[19] By the 9th century, Arab and Persian merchants began establishing semi‑permanent outposts.[20] Earlier external references like the Periplus of the Erythraean Sea had spoken of Rhapta,[21] a major trading emporium believed to have been located along the East African coast. This indicates that by the early medieval period, Muslim traders were embedding themselves within successor coastal towns and their surrounding economies.[22]

In many coastal towns, as traders began to embed themselves, they entered into marriages within local communities, contributing to the formation of a mixed‑identity mercantile elite,[23] though the extent and social dynamics of such intermarriage varied across different Swahili settlements. This period saw the founding of the earliest stone mosques and the emergence of Islam as a defining feature of coastal urban identity. Swahili civilization emerged in these trading towns as a direct result of sustained contact.[24]

As these processes of permanence, social integration, and urban consolidation matured, their effects became most visible between the twelfth and fifteenth centuries.[25] During this phase, several major Swahili city‑states reached a zenith—though unevenly across the coast—with cities such as Kilwa Kisiwani and the Sultanate of Mogadishu emerging as wealthy, autonomous powers[26] that minted their own coins and invested in grand coral‑built architecture. It was in this era of consolidated coastal power that the systematic push into the interior began in earnest. While caravans were often organized and guided by skilled African intermediaries,[27] they were financed by and conducted for the mercantile Arab elites of the coast, establishing durable economic chains linking the interior’s resources to the coastal global marketplace.[28]

In the sixteenth century, a brief Portuguese intervention introduced disruption that proved significant but temporary.[29] The deeper transformation came with the Omani Arab conquest of Zanzibar in 1698. Under Omani rule particularly during the reign of Seyyid Said trade networks were centralized, financed at scale, and militarized. Large, armed caravans penetrated deep into the Great Lakes region,[30] with Zanzibar emerging as the central commercial hub coordinating long‑distance trade in ivory and enslaved people on an unprecedented scale.[31]

Taken together, the experiences of the Arab conqueror in North Africa and the Arab trader in East Africa demonstrate that Arab engagement and permanence in Africa did not arise from a single moment or method. Instead, they emerged through parallel and largely contemporaneous pathways—one rooted in conquest, settlement, and state formation and the other in commerce, social integration, and maritime exchange. Though distinct in form and pace, both trajectories ultimately enabled sustained penetration into the interior, embedding Arab political, economic, and cultural influence more deeply into the African historical landscape.

1.3 Faith interlocking Conquest and Commerce

Whether through military conquest and state formation in the north or through commerce and settlement along the eastern coast, Arab expansion and engagement with African communities possessed a connective force that bound these trajectories together. Into the interior of Africa, across both trans-Saharan and Indian Ocean-connected regions, Arab expansion was driven by commerce that preceded and facilitated the spread of faith. The earliest traders, whether crossing the Sahara from North Africa or sailing the monsoon routes of the Indian Ocean, were driven primarily by material wealth[32]. However, Islam, the religion they carried, possessed features that made it particularly well suited to the marketplace[33]. It offered a common moral and legal code, grounded in Islamic commercial jurisprudence, governing rules for contracts, trust, and fair dealing that allowed a Berber merchant from North Africa and a Wangara gold trader from West Africa to do business despite their different tongues.[34]

As trade grew and expanded, across many African regions where sustained trade took root, Arab and Persian traders settled, entered into intermarriage with local communities, and facilitated the gradual diffusion of Islam through kinship, household formation, and social integration; the Swahili people represent one prominent example of this broader process along the East African coast.[35]

Thus, Islam became a marker of a shared commercial and social identity rooted in trade practices, marriage, contracts, literacy, and trust, linking the African and Arab worlds as it drew African elites into a wider community of believers. In West Africa, rulers such as the famed Mansa Musa of Mali saw the political and economic benefits of this connection. Adopting Islam connected Mali to the literate, trading world of the north, brought trained administrators to their courts, and amplified their prestige. His pilgrimage to Mecca, beginning in 1324, marked by the large-scale distribution of gold that disrupted markets in Cairo, was the ultimate demonstration of how faith and wealth could fuse together to project power.[36]

In summation, through conquest in the north and commerce in the east, trade and faith became mutually reinforcing forces, extending inland through networks of exchange, law, and social integration, and creating the conditions for wider, more enduring systems of markets, authority, and institutions that would shape African societies over time.

Chapter 2

Standardizing Exchange: Arab Commercial Networks and the Reshaping of African Trade Systems

The political footholds created through conquest in the north and the coastal trading corridors established along the eastern seaboard did not remain confined to Africa’s edges; they enabled the emergence of expansive systems of exchange, production, and governance that tied African regions into wider commercial worlds.

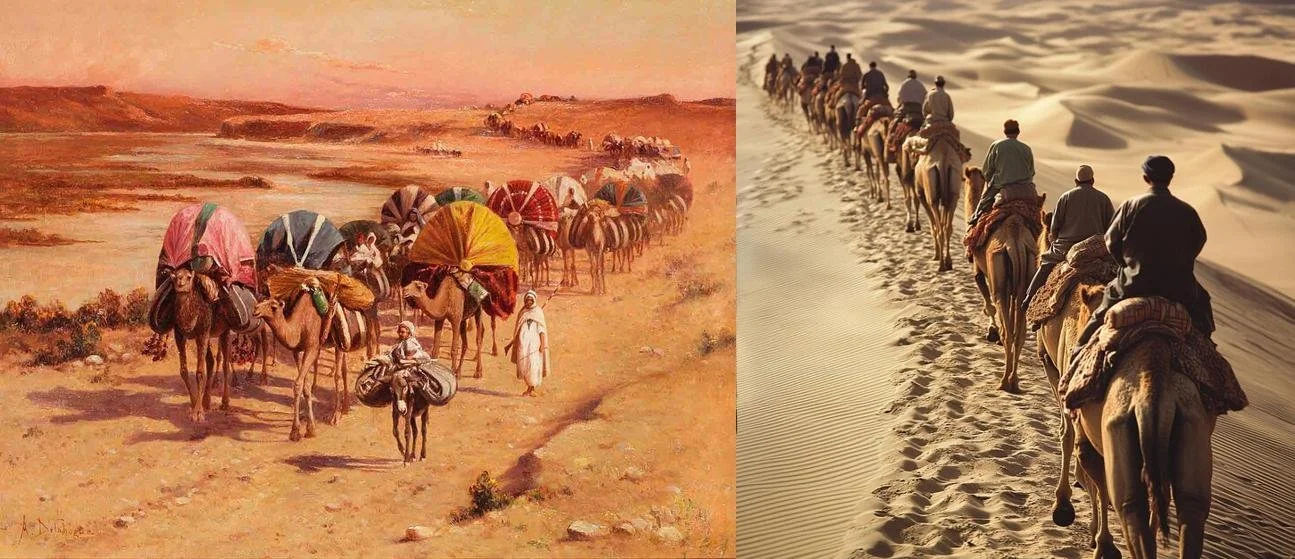

2.1 Caravans and Sahara Sands

As these systems expanded inland, the Sahara emerged not as a barrier but as a conduit. If the ocean functioned as a highway of water, the Saharan deserts operated as highways of sand, with camels serving as the essential vessels that enabled movement and transportation. Crossing this vast expanse demanded extreme endurance and careful coordination. Arab and Berber traders, now bound by shared commercial practices and long-standing interaction across North Africa, organized large caravans, sometimes numbering in the thousands of camels.[37] Once organized, these caravans moved across the desert in coordinated stages, a process that depended on specialized logistical planning, navigational expertise, and established oasis networks to sustain long-distance travel.

A historical engraving or photograph of a Saharan caravan, showing a long line of camels and traders against a desert backdrop. Source: Wikimedia Commons/Wellcome Collection.

These caravans followed routes that had developed over centuries through the movement and exchange of Berber, Saharan, and Sudanic societies which later had been systematized and expanded under Arab‑Islamic trade networks, linking the Mediterranean world to the empires of Sub‑Saharan Africa.[38] One major artery ran from Sijilmasa in present‑day Morocco southward to the Kingdom of Ghana, long known as the “Land of Gold,” whose rulers regulated gold flows into trans‑Saharan trade networks.[39] Another extended from Tripoli to the Kanem‑Bornu Empire near Lake Chad, integrating the central Saharan corridor into wider trans‑Saharan commercial networks.[40] The most renowned routes, however, converged on the city of Timbuktu, which became a central commercial and intellectual hub of the Mali Empire and later of the Songhai Empire.[41] These corridors were not merely paths of movement; they functioned as economic lifelines, transporting salt southward and gold northward, leading to a transformation African ancient kingdoms into sources of wealth and prestige worthy of recognition in the Arab and European worlds.[42]

By the late first millennium, these routes formed a broad commercial space linking the Mediterranean world to Atlantic-facing West Africa and eastward to the Indian Ocean through Africa’s interior.[43] What moved along these routes was not only material goods but also shared commercial norms, including standardized weights, credit practices, written contracts, and customary rules governing trust and obligation, which made long-distance exchange workable across regions.[44] These shared expectations around measurement, contracting, and oversight enabled caravan trade to function across vast distances without implying centralized governance.

2.2 Commodities and Exchange: Africa’s Exports and Imports

As these routes sustained regular movement across Africa’s interior, they brought African supply and external demand into sustained interaction, gradually shaping both the commodities African societies supplied to long‑distance markets and the goods introduced into the continent in return by the Arab world.[45]

2.2.1 Africa’s Exports

With long-established routes increasingly systematized through regular movement, shared norms, and political oversight, African regions were able to participate reliably in long-distance markets as suppliers, responding to external demand while drawing on local ecological and political capacities.

Across markets such as Zanzibar on the Swahili coast and Timbuktu in the western Sahel, African regions supplied commodities that sustained demand across the Islamic world and beyond.

West Africa as a region emerged within trans‑Saharan trade networks primarily as a major gold‑producing region, drawing especially on the Wangara and Bambuk fields. Arab geographers such as al‑Bakri and al‑Idrisi recorded detailed accounts of this trade, including descriptions of Ghana’s regulation of gold nuggets and the practice of silent barter.[46] While not the only commodities produced in the region, gold became the principal export for which West Africa was known, supplying the dinars that underpinned the monetary systems of the Islamic world and, indirectly, medieval Europe.[47]

East Africa emerged within Indian Ocean commerce as a major supplier of ivory, drawing on its substantial elephant populations to meet demand across the western Indian Ocean basin. While the region traded in multiple commodities, ivory became one of the principal exports for which it was known. The Kilwa Chronicle attributes the prosperity of Kilwa to the ivory and gold trade originating from the Sofala hinterland, and archaeological evidence confirms ivory as a staple cargo aboard Indian Ocean vessels.[48]

Enslaved people constituted another element of this commercial system, though the scale, organization, and regional intensity of this trade varied significantly across time and place within both trans‑Saharan and Indian Ocean contexts.[49] Arab commercial records from Zanzibar during the Omani period list enslaved individuals alongside ivory and cloves, while the travel accounts of Ibn Battuta provide contemporary descriptions of slave markets operating in Swahili city‑states during the fourteenth century.[50]

Additional exports included rock salt from Saharan mines such as Taghaza, which stood at the logistical center of trans‑Saharan trade; animal skins, valued for elite display; and hardwoods such as ebony.

Such commodities, circulated in steady and organized flows across these networks, generated revenue, stimulated regional production, and reinforced political authority within the societies that controlled their extraction and distribution, thereby contributing materially to broader patterns of economic development across the Sahel and beyond.[51]

2.2.2 Africa’s Imports

As African regions supplied valued commodities into these expanding networks, they also absorbed a range of manufactured and prestige goods from across the connected commercial world:

Indian and Persian textiles, particularly cotton cloths such as calicoes and dyed fabrics, became markers of wealth and status along the East African coast. Portuguese customs records from the sixteenth century describe the regular arrival of Gujarati and Indian cloth in coastal ports, while later Omani administrative documents from Zanzibar record the importation and redistribution of large quantities of cloth through local markets, underscoring their centrality to coastal commerce.[52]

Chinese porcelain and glass beads reached African markets primarily through Indian Ocean maritime routes, moving from South China through intermediary entrepôts in Southeast Asia and India, then onward across the monsoon corridors of the Arabian Sea and through Red Sea and Persian Gulf networks before arriving at Swahili coastal ports. From these coastal centers, they circulated inland through established trade routes.[53] These materials entered African markets in large quantities and are among the most common archaeological finds at Swahili stonetown sites. Imported ceramics, especially celadon and blue‑and‑white porcelain, now serve as key chronological indicators in archaeological stratigraphy.[54]

Weapons, including high‑quality steel blades from Yemen and Damascus as well as imported firearms in later centuries, entered African markets primarily through Red Sea, Persian Gulf, and Indian Ocean maritime routes, and through trans‑Saharan corridors linking North Africa to the Sahel. These imports were significant not merely as prestige goods but as instruments that strengthened the military capacity of rulers engaged in long‑distance commerce, enabling them to protect trade routes, enforce taxation, and consolidate political authority within expanding states.[55]

Other imports included spices and dates, which entered African markets largely through Red Sea and Indian Ocean maritime routes and became integrated into coastal and Sahelian patterns of consumption, hospitality, and elite display. Paper, transmitted through North African and Middle Eastern trade circuits into both trans‑Saharan and Indian Ocean networks, proved especially consequential: its availability facilitated the expansion of written contracts, judicial records, Quranic schooling, and administrative correspondence across commercial centers such as Timbuktu, Jenne, and the Swahili towns. In this way, imported paper materially supported the consolidation of literate bureaucratic and scholarly traditions tied to trade and governance.[56]

This was not a primitive exchange. It was Africa inserting itself as a crucial producer in a pre-modern global economy, its resources driving demand across hemispheres. The archaeological record gold coins minted in Kilwa, Chinese porcelain in Great Zimbabwe, Arab glass in Ife—testifies to the continent's deep integration into these long-distance networks.

Taken together, these exchanges demonstrate that the trade networks systematized and expanded through Arab commercial activity in both North Africa and along the East African coast did more than facilitate smoother exchange between African societies and external markets; they integrated African regions into enduring circuits of global commerce. Archaeological finds—such as locally minted gold coins in Kilwa, Chinese ceramics in Great Zimbabwe, and imported glass in Ife—attest not only to sustained participation but to Africa’s active insertion into interconnected economic worlds that linked the Mediterranean, the Indian Ocean, and the wider Afro‑Eurasian sphere.[57]

2.2 Introduction of New Mechanisms to Manage Value and Exchange

As trade expanded along the routes systematized and introduced by Arab commercial networks, it required new mechanisms to manage value and exchange. In that regard, Arab merchants introduced standardized weights, such as the mitqal for measuring gold dust, operating within Islamic commercial law and adopted across regions in varying degrees, thereby reducing disputes and enabling transactions between distant markets to function on shared and trusted measures of value.[58]

A photograph of historical Swahili or Islamic brass weights used for measuring gold. Source: National Museums of Kenya online archive.

Monetary systems also evolved in response to the expanding scale and complexity of exchange. Prior to the wider circulation of standardized coinage and shell currencies, many regions relied heavily on localized barter, gold‑dust weighing, or commodity exchange, practices that often required direct negotiation and could limit transactional scale across distant markets.

As trans‑Saharan and Indian Ocean trade intensified, gold coinage—minted in major Islamic centers such as Kairouan, Cairo, and later Almoravid and Almohad North Africa—circulated widely across North Africa and the Sahara through Arab‑Berber commercial networks, linking Sahelian gold production to Mediterranean monetary systems.[59] At the same time, cowrie shells—procured in the Maldives and transported through Indian Ocean maritime networks in which Arab and Arab‑Swahili merchants played a central and documented role in procurement, shipping, redistribution, and the management of coastal entrepôts—entered African markets in large quantities and became a widely recognized medium of exchange across West and East Africa.[60]

The portability, divisibility, and relative uniformity of cowrie shells, together with the standardized weight and widely recognized value of gold coinage, facilitated smaller‑scale transactions, market taxation, and wage payments, smoothing exchange across regions that lacked minting infrastructure hence strengthening commercial integration across diverse African societies.[61]

In parallel, structured marketplaces, ports, and customs houses expanded and were increasingly organized along commercial norms transmitted through Arab and Arab‑Berber trading networks. Through shared contractual practices, fiscal instruments, and maritime and caravan coordination, these networks helped regularize port administration, customs collection, and market oversight across both the Swahili coast and the Sahel. Rulers of Swahili city‑states and Sahelian empires levied duties on goods within this expanding commercial framework, channeling revenues into the construction of mosques, fortifications, and administrative centers. In this way, Arab‑linked trade did not merely move commodities; it streamlined markets and embedded commerce within the institutional foundations of state formation.[62]

2.3 Language, Literacy, and Law within the Expanding Trade Networks

As the commercial networks systematized through Arab trade deepened across North, West, and East Africa, they carried not only goods and monetary instruments but also linguistic and intellectual frameworks embedded within Islamic commerce. Arabic increasingly functioned as a language of law, scholarship, and trade administration within these expanding markets. Swahili, while fundamentally Bantu in structure, absorbed a substantial Arabic vocabulary related to calculation, contracts, taxation, religion, and governance, reflecting the practical domains in which trade, literacy, and authority converged.[63]

The same corridors that transmitted coinage, cowries, and contractual norms also facilitated the spread of Quranic schooling and manuscript culture across regions ranging from Jenne in Mali to Lamu on the Kenyan coast.[64] Arabic script was adapted to local languages, producing Ajami writing traditions in Hausa and Swahili that enabled record‑keeping, legal documentation, and correspondence within commercial and political systems.[65] Through written contracts, judicial records, poetry, and chronicles, African scholars and administrators participated in a widening intellectual sphere shaped in part by the commercial integration discussed above. In this sense, the linguistic transformations that followed were not incidental; they were institutional consequences of the trade systems introduced and expanded through Arab networks.[66]

Taken as a whole, the developments traced in this chapter reveal that Arab commercial engagement in North, West, and East Africa did not simply expand the volume of exchange; it standardized the mechanisms through which exchange operated. Through the systematization of caravan and maritime routes, the diffusion of shared weights and monetary instruments, the coordination of ports and customs regimes, and the transmission of legal and linguistic frameworks embedded in Islamic commerce, Arab-linked networks helped regularize markets across vast and diverse regions of the continent. In doing so, they integrated African societies more deeply into trans-regional economic circuits while simultaneously reshaping local institutions of governance, administration, and authority. The marketplace that emerged was therefore not incidental to political transformation; it was foundational to it.

Chapter 3

Institutional Expansion and the Political Economy of Slave Trading under Arab-Linked Systems

Slavery existed in multiple African societies prior to Arab expansion, functioning within kinship structures, judicial systems, and local political economies.[67] However, from the seventh and eighth centuries onward, Arab commercial and political expansion connected these localized systems to wider Afro‑Eurasian demand through increasingly coordinated mechanisms—standardized weights, monetized exchange, regulated ports, and organized caravan structures. Rather than initiating slave trading on these routes, Arab merchants and state authorities integrated, regularized, and expanded existing practices into sustained export circuits across trans‑Saharan and Indian Ocean networks.[68] Over time, this integration intensified scale, widened geographic reach, and embedded the trade in enslaved persons within broader systems of commercial organization, most visibly in the trans‑Saharan system and, later, in the Omani‑centered expansion of the western Indian Ocean.

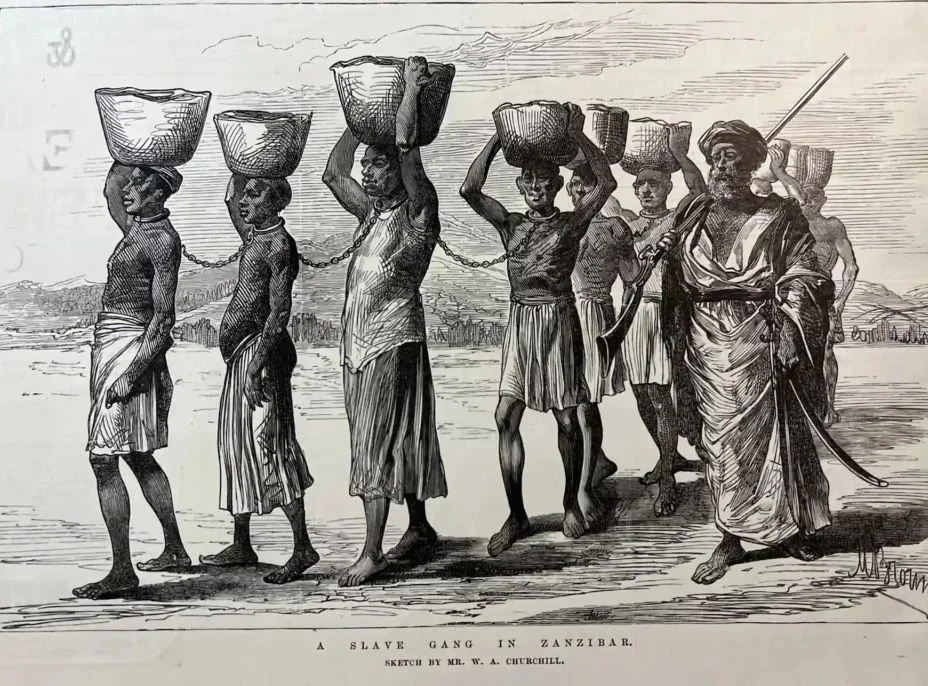

3.1 Zanzibar as an Arab Institutional Hub for Slave System

As Arab commercial expansion shifted its center of gravity toward the western Indian Ocean, Zanzibar became the principal territorial base of Omani Arab political authority in East Africa.[69] By the nineteenth century, under the rule of the Omani Arab sultans, the island had emerged as a central node in regional commerce.

Its deep-water harbor, strategic position along monsoon-driven maritime routes, proximity to mainland caravan termini, and the relocation of the Omani political capital to Zanzibar in 1840 reinforced its dominance.[70] Following the consolidation of Omani authority over the island in 1698, and especially during the reign of Seyyid Said (r. 1806–1856), Zanzibar developed into a major commercial capital coordinating long‑distance trade in cloves, ivory, and other regional commodities.[71]

As clove plantations expanded and caravan routes from the mainland were regularized, enslaved labor became increasingly central to this commercial system. With slaves established as a major commodity, the scale of slave exports grew over the course of the nineteenth century alongside the expansion of plantation agriculture and ivory exchange.[72] By the mid-nineteenth century—particularly between the 1840s and 1870s—Zanzibar handled, by some scholarly estimates, tens of thousands of enslaved persons annually.[73] These exports were integrated into the western Indian Ocean slave-trading system centered on Omani-Arab authority, linking Zanzibar with ports in Oman, the Persian Gulf, and coastal East Africa. Cumulative removals within this western Indian Ocean system over the nineteenth century are estimated in the several hundreds of thousands.[74]

A historical photograph or engraving of the Zanzibar slave market, showing the holding chambers. Source: British Library or Wellcome Collection.

While cloves and ivory generated substantial revenue within the island’s economy, the rapid expansion of clove plantations on Zanzibar and neighboring Pemba created sustained demand for labor that was increasingly met through the large‑scale acquisition and movement of enslaved persons.[75] Enslaved individuals thus functioned simultaneously as plantation labor within the island economy and as export commodities within Omani‑linked Indian Ocean markets. To sustain this dual system, Arab merchants at the coast working with African intermediaries operating in the interior financed and organized large caravans that penetrated deep into the Great Lakes region and adjacent territories.[76]

Within this institutional framework, the scaling of the trade depended not merely on individual caravan leaders but on coordinated political and commercial structures. Omani Arab political authority provided diplomatic protection, customs regulation, and fiscal oversight that secured merchant operations along the coast, while merchant houses extended credit, supplied arms, and organized multi‑year caravan expeditions into the interior. Swahili‑Arab commercial elites operated as intermediaries between inland capture zones and coastal export markets, integrating regional networks into the revenue structures of Zanzibar’s port economy. Figures such as Hamad bin Muhammad al‑Murjebi (famously known as Tippu Tip) emerged within this already institutionalized system as prominent caravan leaders, linking inland capture zones to coastal markets.[77]

Through Omani‑Arab political backing, regulated port administration, credit‑financed caravan networks, and integration into Indian Ocean markets, Zanzibar became the central export hub of the western Indian Ocean slave trade in the nineteenth century. The commercialization and monetization systems established under Omani authority transformed enslaved persons into revenue‑generating labor and export commodities within a structured maritime economy. Without these coordinated fiscal, logistical, and commercial mechanisms, the scale, regularity, and global visibility of the East African slave trade—particularly through Zanzibar—would likely not have developed in the form documented by contemporary observers and later historians.[78]

3.2 Slave Trade Scaling in the Trans-Saharan System

Slave trading and systems of servitude operated within early North African societies prior to Arab expansion. However just like Zanzibar, from the seventh and eighth centuries onward, Arab‑Islamic political authority and commercial institutions reorganized these practices into regulated caravan networks and taxable urban markets, standardizing and monetizing them within structured desert export systems.[79] From the eighth and ninth centuries onward, sustained caravan traffic would move enslaved persons northward across the desert into Maghrebi and Mediterranean markets.[80]

Over centuries, Arab‑Islamic rulers and merchant networks in North Africa did not merely inherit existing slave movements; they expanded them through state protection of caravan routes, application of Islamic commercial law, and incorporation of slave sales into taxable urban markets. This institutional backing enabled sustained large‑scale desert export systems under Arab‑Islamic governance, demonstrating that political authority, commercial regulation, and fiscal extraction were central to the trade’s expansion and monetization in North Africa.

Islamic commercial law structured this trade through Juridical frameworks that defined categories of enslavement, governed conditions of sale, and regulated contractual exchange within recognized market settings.[81] Transactions were documented within broader commercial jurisprudence that treated enslaved persons as legally codified commodities, integrating their sale into standardized systems of weights, currency, and taxation.[82] In this respect, Arab‑Islamic legal institutions transformed dispersed practices into regulated market exchanges operating across desert corridors.

Beyond legal codification and market regulation, North African states did not merely permit this commerce; they extracted fiscal value from it. Customs duties were levied at Saharan termini such as Sijilmasa and later urban centers including Fez, Tunis, and Cairo, where caravans were processed, assessed, and taxed under state authority.[83] State oversight of caravan routes, protection of trade corridors, and incorporation of slave duties into treasury systems reveal a monetized structure comparable in institutional logic though earlier in chronology to Zanzibar’s nineteenth‑century fiscal regime.

From these North African nodes, enslaved persons were redistributed into Mediterranean and Middle Eastern markets, where urban absorption in Maghrebi cities, military recruitment in Islamic polities, and resale into Ottoman and broader Mediterranean systems extended the commercial chain beyond the desert frontier.[84]

3.3 Extension of Standardized Slave Trade in the Western Sahel

As Arab authorities standardized and secured caravan routes across North Africa, they opened sustained corridors to the western Sahel (corresponding broadly to parts of modern-day West Africa), south of the Sahara and beyond the core regions under early Arab political control in North Africa.[85]

In this Sahelian zone lay polities such as ancient Ghana, Mali, Songhai, Takrur, and later Hausa states. The consolidation of these corridors enabled more regular exchange between North Africa and the Sahel, including the northward movement of enslaved persons within organized trans‑Saharan caravans.[86] Prior to this sustained integration, systems of servitude in parts of the western Sahel had remained largely localized, and exchanges with North African markets were limited in scale and irregular in organization.

In a nutshell, the consolidation of Arab political authority and commercial regulation in North Africa transformed intermittent desert exchanges into sustained and institutionally supported slave export systems. Through the protection of caravan routes and the application of Islamic commercial law, Arab‑Islamic institutions standardized and monetized the movement of enslaved persons. This process converted localized Sahelian servitude into structured northward export circuits tied to North African redistribution centers and Mediterranean markets over centuries.

3.4 Commercial Demand and Functional Allocation of Enslaved Persons

Having established how Arab-linked institutions scaled slave exports across Zanzibar, North Africa, and the western Sahel, it is necessary to examine how those systems reshaped the function and allocation of enslaved persons within long-distance markets.

The Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan export trades, operating under Arab-linked commercial systems, differed in important respects from certain forms of slavery practiced within African societies. Many internal systems of servitude in precolonial Africa were embedded in kinship structures, debt arrangements, or judicial penalties and, in some cases, allowed for social incorporation over time.[87]

As routes were secured, ports regulated, and exchange standardized under Arab-linked commercial systems, the long-distance export trade increasingly operated according to principles of profit, demand, and supply. What had once been localized systems of servitude became integrated into monetized markets where captives were assessed, priced, and moved according to commercial calculation.[88] Individuals were thus commodified within structured market systems that separated them permanently from their home communities.

As slave exports expanded and enslaved persons became central commodities within long‑distance trade, conflicts between African societies intensified. Captives drawn from regions such as Nyamwezi and Yao territories in East Africa, Great Lakes polities, and Sahelian zones integrated into trans‑Saharan networks[89] were increasingly obtained through warfare and organized raiding aimed at supplying expanding markets.[90] The growing profitability of slave trading redirected political and military priorities toward the capture of individuals for sale within structured commercial circuits.

The purposes for which enslaved persons were compelled to serve varied across both Indian Ocean and trans‑Saharan systems. In plantation zones such as Zanzibar and Pemba, labor was concentrated in clove cultivation. Along northern routes, enslaved persons moving through trans‑Saharan corridors were absorbed into urban households in Maghrebi cities, incorporated into military formations, placed in agricultural estates in North Africa, or redistributed into Ottoman and Mediterranean markets.[91]

Not all enslaved individuals were exported beyond Africa; some were retained within North African societies or within African polities engaged in regional trade, where they served as agricultural laborers, domestic servants, soldiers, or court dependents.[92] The diversity of these labor roles demonstrates that enslaved persons functioned not only as export commodities but also as coerced labor assets within African and Mediterranean economies structured under Arab‑linked commercial and political systems.

3.5 Social, Economic and Political Consequences of Institutionalized Slave Trade Expansion

The expansion of export‑oriented slave trading under the Arab‑linked political, legal, and commercial systems examined above produced significant social, economic and political consequences for affected African societies.

Beyond demographic losses, the intensification of raiding and warfare redirected political incentives toward participation in capture and exchange networks, weakening long‑standing inter‑community alliances and increasing suspicion and hostility between neighboring societies.[93] In this context, some political authorities derived revenue and military power from participation in capture and exchange networks, further reshaping state priorities around control of trade corridors and access to external markets.

In regions tied to Zanzibar’s caravan networks, including Nyamwezi and Yao territories, repeated raiding destabilized local authority and fractured alliances as neighboring communities were drawn into capture and sale circuits.[94] In the western Sahel, where trans‑Saharan corridors linked polities such as Songhai and later Hausa states to North African markets, participation in slave trading likewise generated insecurity and rivalry between communities competing for access to desert routes.[95]

Participation was not uniform across these regions, but where Arab-linked commercial systems penetrated most deeply, political restructuring followed. In parts of East Africa connected to Zanzibar’s caravan economy, leaders such as Mirambo of the Nyamwezi in the nineteenth century consolidated authority by aligning with coastal merchants and reorganizing military forces around sustained raiding for captives, while figures like Tippu Tip operated within the same commercial-military structure linking inland warfare to coastal export markets.[96]

This pattern of political restructuring was not confined to East Africa. In segments of the western Sahel tied to trans-Saharan corridors, access to desert routes and North African markets likewise reshaped state competition, as rulers sought to control trade arteries that now yielded fiscal and military advantage. The late sixteenth-century Moroccan invasion of Songhai, driven in part by the desire to dominate trans-Saharan gold and slave routes, illustrates how control of these corridors could provoke major interstate conflict.[97]

By contrast, other polities resisted integration into Arab-linked commercial circuits. In parts of the western Sahel, the Mossi states long resisted incorporation into trans-Saharan trading systems, conducting counter-raids and limiting merchant penetration, which preserved political autonomy but reduced direct access to desert trade revenues.[98] In East Africa, certain inland polities initially restricted coastal merchant entry to prevent destabilization, though over time neighboring groups that aligned with caravan networks accumulated greater military resources and commercial advantage.

Resistance took multiple forms. Fugitive communities established settlements beyond direct control of raiding networks, and rebellions occurred within plantation settings in Zanzibar and elsewhere.[99] These acts of resistance demonstrate that enslaved individuals and affected communities were not passive subjects within the system but active participants in contesting it.

In conclusion to this chapter, the cumulative evidence across East Africa, North Africa, and the western Sahel demonstrates that Arab actors did not introduce slavery into Africa, but they decisively transformed its scale and structure. Through the consolidation of political authority, the protection and regulation of caravan and maritime routes, the application of Islamic commercial law, and the integration of slave sales into taxable market systems, Arab‑linked institutions converted localized systems of servitude into sustained export economies. These systems extended beyond the regions of direct Arab settlement, shaping inland political restructuring in the Great Lakes region, fiscal regimes in North African urban centers, and export corridors linking the Sahel to Mediterranean and Indian Ocean markets. The result was not the creation of slavery, but the institutional streamlining and geographic expansion of slave trading across African regions and beyond African borders. The social fragmentation, political militarization, and economic reorientation that followed were inseparable from the commercial and administrative frameworks that enabled this expansion.

Chapter 4

Power Shift: European Expansion through Established Arab Systems

The commercial, fiscal, and logistical systems consolidated under Arab political and mercantile authority across the Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan worlds formed the structural environment within which European expansion advanced in the nineteenth century. European explorers and colonial agents entered regions already organized by caravan corridors, maritime routes, fiscal systems, and port administrations, and they initially operated through these existing frameworks—relying on coastal intermediaries in East Africa, redirecting trans-Saharan flows in the western Sahel, and appropriating administrative structures in North Africa before consolidating direct control.[100]

4.1 European Reliance on Established Arab and Arab-Swahili Trade Networks

European penetration of the African interior in the nineteenth century would have been severely constrained—and in many regions substantially delayed—without the long-established commercial corridors, administrative precedents, fiscal systems, and geographic knowledge networks created under Arab, Arab-Berber, and Arab-Swahili authority.

In the absence of these routes and intermediaries, European expeditions would have faced acute logistical shortages, navigational uncertainty, unfamiliar or resistant political authorities, and a lack of established provisioning depots, caravan credit networks, and recognized customs administrations capable of sustaining long-distance movement and financing inland occupation.[101]

Across North Africa, European powers built upon existing administrative and fiscal systems rooted in earlier Islamic governance; in the western Sahel, they redirected trans-Saharan trade arteries that had linked Mediterranean markets to Sudanic polities for centuries; and in East and Central Africa, explorers such as Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke followed established caravan routes inland from Bagamoyo that had long been used in the ivory and slave trades.[102]

They did not merely traverse existing routes; they incorporated their custodians into the machinery of expansion. European expeditions contracted established Arab and Swahili caravan leaders as guides, brokers, and diplomatic intermediaries in the Eastern corridor. A clear case is Henry Morton Stanley’s arrangement with Tippu Tip in the late 1870s, whereby Tippu Tip supplied porters, secured passage through contested territories, and later served as governor for the Congo Free State under King Leopold II—demonstrating direct reliance on pre-existing commercial authority.[103]

The reliance was total. When David Livingstone ventured into the interior, his survival often hinged on the cooperation of Arab traders like the infamous Tippu Tip, who controlled the territory and supply lines. European expedition journals from this period are filled with acknowledgments sometimes grudging of their debt to this pre-existing infrastructure. The "blank spaces" on European maps were, in fact, intricately detailed in the mental cartography of Arab and Swahili merchants.

This practice extended beyond the Eastern corridor. In the western Sahel, French administrators worked through merchant families and Islamic judicial officials to organize taxation and regulate trade, while in North Africa they maintained and repurposed Muslim legal courts (mahakim) and fiscal offices staffed by local elites.[104]

European expedition journals themselves attest to this dependence: Henry Morton Stanley’s Through the Dark Continent records negotiations with coastal brokers and caravan leaders for porters and passage, while Richard Burton’s travel accounts describe reliance on Swahili intermediaries for navigation and political mediation.[105] These accounts reveal that European expeditions depended not simply on African labor, but on the accumulated commercial intelligence of Arab trading networks/channels, their knowledge of safe corridors, political alliances, provisioning points while they negotiated for access to inland regions.

Thus, it can be concluded that European explorers did not encounter institutional vacuums; they found regions already structured by functioning commercial, fiscal, and administrative systems established under Arab authority, systems that they entered and later redirected for their own imperial purposes.

4.2 Reconfiguration of Arab–European Relations

While European expansion initially advanced through established Arab-linked commercial channels, the evolving political ambitions of imperial powers gradually altered these relationships, setting the stage for tensions that would reshape the existing system.

In the earlier phases of European arrival, cooperation with Arab-linked commercial elites was largely pragmatic across multiple regions, as European agents operated through established caravan authorities in the east, merchant networks in the western Sahel, and Islamic judicial-fiscal institutions in North Africa.

As imperial ambitions sharpened after the 1870s, this accommodation gave way to competition. In East Africa, anti-slavery enforcement and chartered company rule disrupted coastal mercantile authority; in North Africa, formal occupation brought Islamic judicial and fiscal institutions under direct colonial supervision; and in the western Sahel, French military penetration reoriented trans-Saharan trade networks toward metropolitan control.[106] Across these regions, expanding European sovereignty progressively undermined the intermediary roles that had initially facilitated their entry.

Building upon the anti-slavery enforcement already noted in East Africa, European abolitionist movements more broadly reframed both the Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan slave trades as targets of moral and political intervention. British naval patrols began intercepting dhows suspected of transporting enslaved persons, and diplomatic pressure was applied to the Sultan of Zanzibar to sign treaties restricting slave exports.[107] While humanitarian rhetoric shaped public justification, these measures simultaneously disrupted the commercial foundations upon which Arab-linked mercantile networks in the east and, by extension, connected inland circuits depended.

Alongside abolitionist enforcement and expanding colonial supervision, a further factor accelerating deterioration was the rise of chartered companies endowed with quasi-sovereign authority. In East Africa, the Imperial British East Africa Company and the German East Africa Company assumed administrative and fiscal powers previously mediated through coastal Arab-Swahili elites. These companies imposed customs regimes, claimed territorial jurisdiction, and bypassed established mercantile intermediaries, thereby transforming earlier cooperation between Arabs and Europeans into direct competition for authority.[108]

Beyond the institutional displacement introduced by chartered company rule, the increasing racialization of late nineteenth-century imperial ideology further reshaped relations. Earlier exploratory phases had been marked by pragmatic collaboration; however, as formal empire expanded, European administrative discourse increasingly portrayed Arab and Swahili commercial actors not as partners but as obstacles to “civilizing” missions, particularly in anti-slavery rhetoric. This ideological shift reinforced emerging administrative exclusions, hardened political boundaries, and further reduced the space for negotiated coexistence.[109]

Reinforcing this ideological and administrative exclusion, shifts in global commodity markets further destabilized established networks. The declining profitability of slave trading, fluctuating ivory demand, and the integration of African commodities into metropolitan-controlled export systems altered commercial incentives in ways that favored direct European control. European firms increasingly sought to monopolize procurement channels and redirect trade toward coastal enclaves under colonial supervision, thereby weakening Arab-linked caravan circuits that had previously coordinated inland exchange.[110]

Inland political realignments compounded these pressures. Some Sudanic and East African rulers recalibrated alliances toward European powers as military technology and diplomatic leverage shifted the regional balance. Such recalibrations diminished the brokerage position of Arab-linked intermediaries who had long mediated between inland polities and coastal markets, thereby accelerating the erosion of earlier commercial hierarchies.[111]

Taken together, abolitionist intervention, chartered company rule, ideological exclusion, shifting commodity markets, and inland political realignments transformed earlier cooperation into structured rivalry. What began as reliance on Arab-linked commercial systems culminated, particularly after the Berlin Conference of 1884–85, in formal territorial claims and the progressive displacement of the very intermediaries who had facilitated European entry into the interior.

4.3 Treaties, Resistance and Final Displacement of Arab Authority by Europeans

As the structural reconfiguration outlined above translated into formal assertions of sovereignty, rivalry between European authorities and Arab-linked elites materialized through treaties, contested jurisdiction, and armed resistance.

Across the continent, European colonial expansion frequently advanced through treaty-making with local authorities as a formal instrument of territorial acquisition. These agreements often drafted in European legal terminology—were presented to rulers as arrangements concerning trade, protection, or commercial regulation; yet many contained provisions that ceded sovereign rights, fiscal authority, or administrative jurisdiction to European powers, thereby converting commercial footholds into juridical claims of rule.[112]

Within this treaty-driven expansion, Arab-linked commercial and political elites across East Africa, North Africa, and the western Sahel long accustomed to treaty-making within mercantile frameworks did not always interpret these agreements as irrevocable transfers of sovereign authority. This divergence in interpretation proved consequential. In East Africa, treaties concluded between the Sultanate of Zanzibar and German and British representatives in the late 1880s transferred mainland administrative control to chartered companies; in North Africa, agreements following the French invasion of Algeria (1830) and later protectorate arrangements in Tunisia (1881) subordinated existing Islamic judicial and fiscal authority to European oversight; and in parts of the western Sahel, French “protectorate” treaties redefined commercial cooperation as territorial submission. In each case, asymmetrical legal interpretation converted commercial agreements into instruments of sovereignty transfer, resulting in the progressive loss of political authority previously exercised by Arab-linked elites.[113]

The consequences of these treaty-induced transfers of authority were neither uniform nor passive; responses among Arab-linked elites varied according to region and circumstance. Sultan Barghash of Zanzibar (r. 1870–1888) pursued infrastructural modernization and diplomatic balancing strategies in an effort to counter expanding British and German influence following mounting treaty pressure.[114] Despite these efforts, he was compelled to concede mainland territories to European commercial and political interests. Tippu Tip, a prominent Zanzibari trader, entered into a temporary arrangement with King Leopold II of Belgium and was appointed governor within the Congo Free State, reflecting an attempt to preserve influence within a rapidly shifting political order. This collaboration proved unstable, and he was eventually marginalized as European colonial administrations consolidated direct control.[115]

The treaty-driven transfer of authority did not proceed uncontested. In several regions, resistance emerged where Arab-linked elites perceived sovereignty to be under direct threat. The Bushiri Rebellion (1888–1890) in German East Africa, led by Bushiri bin Salim—an Arab plantation owner of Omani descent—mobilized Arab landholders, Swahili merchants, and African communities against the German East Africa Company in defense of coastal political and commercial autonomy.[116] Comparable patterns appeared elsewhere: in North Africa, resistance under figures such as Emir Abd al-Qadir in Algeria and later opposition to French protectorate authority in Tunisia reflected attempts to defend Islamic judicial and fiscal sovereignty; in the western Sahel and Saharan corridors, Tuareg and Moorish elites resisted French military penetration that threatened long-standing trans-Saharan trade hierarchies.[117] Although these movements were ultimately suppressed, they demonstrate that displacement of Arab-linked authority was frequently contested rather than passively accepted.

With treaties imposed, resistance suppressed, and protectorates formalized, the authority once exercised by Arab-linked commercial and political elites steadily passed into European hands. By the close of the nineteenth century, caravan networks, port administrations, fiscal systems, and trade hierarchies that had been developed and managed under Arab authority for centuries were subordinated to colonial rule or absorbed into imperial administrative frameworks. European powers did not enter institutional vacuums; they assumed command of an economy and logistical order long established, redirecting its structures to serve metropolitan imperial objectives.

Chapter 5

Politically, Economically & Socially: The Living Legacy of Arabs in Africa

It is clear that for over a millennium, Arab commercial expansion reshaped African coastlines and deserts, consolidated caravan corridors and maritime highways, standardized markets, embedded religious and legal institutions, and integrated diverse regions into wider Afro‑Eurasian systems of exchange. These processes also intensified extraction, most visibly through the scaling of slave trading structures. When European imperial powers entered this already connected landscape, they did not construct entirely new systems; they appropriated existing routes, absorbed established institutions, and gradually displaced Arab political and commercial dominance. Yet displacement did not erase earlier formations. The linguistic shifts, urban configurations, religious institutions, and economic orientations forged during this long era of interaction continued to structure African societies well beyond the transfer of imperial authority.

5.1 North Africa: Conquest, Arabization, and Structural Resilience

The most extensive and enduring transformation occurred in North Africa, where military conquest, migration, and political consolidation produced sustained structural reordering. The territories corresponding to modern Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco represent the most comprehensive zone of Arab political settlement and linguistic change. Prior to the seventh century CE, this region consisted of Byzantine provinces, Amazigh (Berber) polities, and residual Roman provincial structures in North Africa, particularly Ifriqiya (modern Tunisia and eastern Algeria).[118] It formed part of the Roman and later Byzantine Mediterranean political and commercial order and was not culturally or linguistically Arab prior to the coming of Arab forces.[119]

The Arab conquest began with the invasion of Egypt in 639 CE under ʿAmr ibn al-ʿĀṣ, a campaign that was militarily decisive in major urban centers. The longer-term process of Arabization, however, unfolded gradually. Early Arab armies were limited in number, and sustained transformation occurred through subsequent migration, settlement, and tribal movements—particularly the eleventh-century migrations of the Banū Hilāl and Banū Sulaym. Their demographic and linguistic impact varied in scale and tempo across regions, yet cumulatively accelerated processes of Arabization in large parts of the Maghrib.[120]

These migrations were at times encouraged or redirected by Fatimid political authorities. The Fatimids, an Ismaili Shiʿi caliphal regime that ruled North Africa (909–969 CE) before shifting their capital to Cairo, used tribal movements to consolidate control over the Maghrib.[121] These shifts altered patterns of settlement, language use, and rural organization across sections of the Maghrib. Over time, Arabic became the dominant administrative and scholarly language in most urban centers, while pre‑existing Amazigh (Berber) languages such as Tamazight, Tachelhit, and Kabyle persisted in distinct regional configurations.[122] Crucially, this linguistic and demographic shift outlived medieval political realignments and the later imposition of European colonial rule. Today, across Egypt, Libya, Tunisia, Algeria, and Morocco, Arabic remains the principal language of administration, education, and public life. Islam, the religion transmitted and institutionalized through these earlier processes, continues to structure legal vocabularies, social norms, national identity, and broader expressions of Arabic cultural life.

This institutional and linguistic consolidation was anchored in durable urban centers. North African cities that emerged as Arab‑Islamic political and intellectual centers—Cairo (al‑Fusṭāṭ), Kairouan, Fez, and Marrakesh—retained their status as enduring capitals of religious scholarship, governance, and urban culture well into the Ottoman and colonial periods.[123] Although European powers appropriated administrative sovereignty in the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, they did not dismantle the Arabic linguistic order or the Islamic institutional framework that had taken root centuries earlier.

The Arab‑Islamic configuration of North Africa therefore proved structurally resilient. Colonial rule modified political authority but did not reverse the long-term processes of Arabization and Islamization initiated during the medieval period. The contemporary predominance of Arabic language, Islamic religious practice, and associated cultural forms across the northern region demonstrates the depth and durability of that transformation.

5.2 The Swahili Coast: Mercantile Integration and Enduring Arab-Islamic Urban Legacy

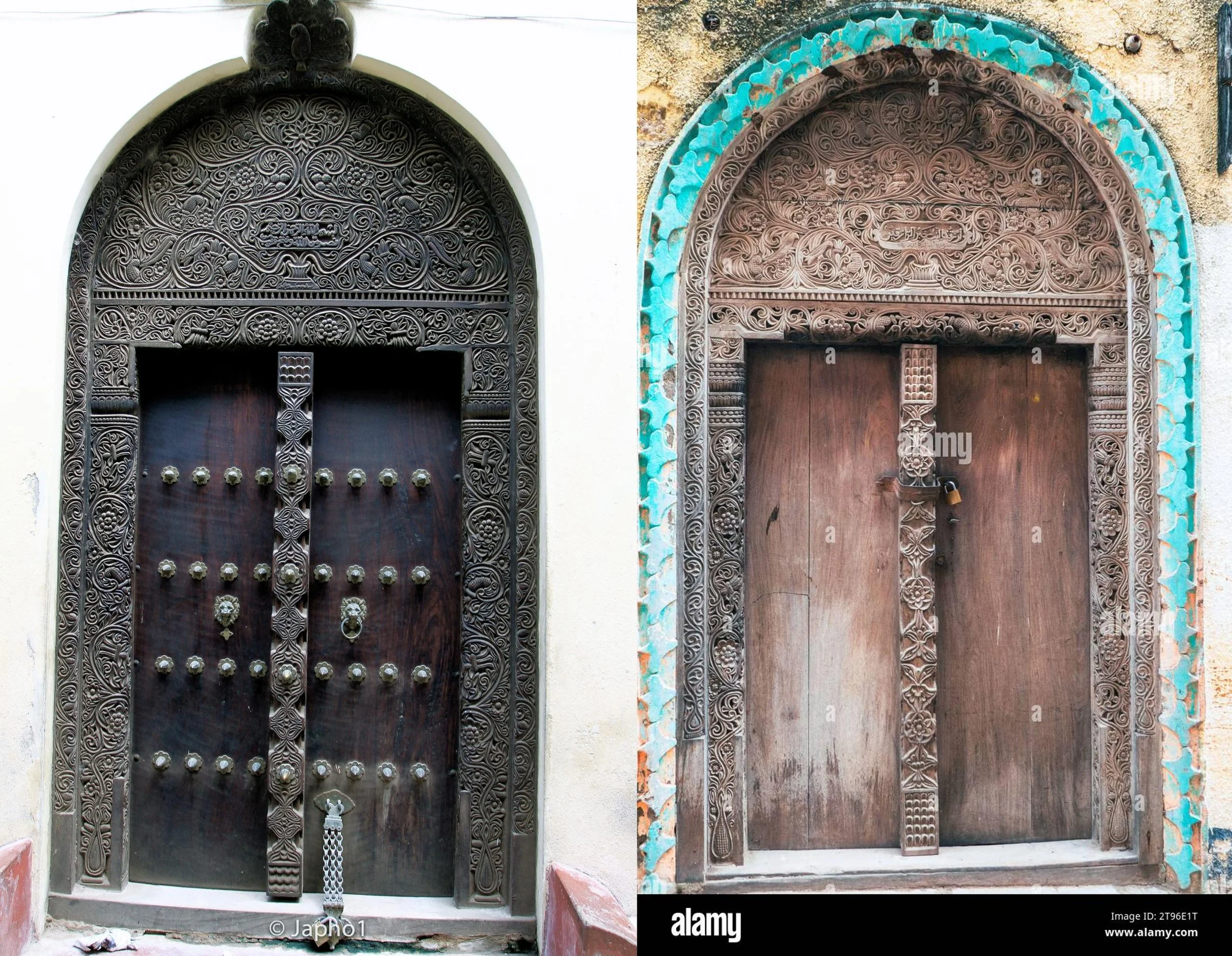

While North Africa underwent conquest-led demographic and linguistic transformation, the East African coast developed through sustained maritime commerce rather than territorial domination. Arab merchants settled seasonally and permanently along the coast, intermarried with local populations, and integrated into existing African trading communities rather than displacing them.[124] This pattern produced an urban culture rooted in commercial partnership and religious affiliation rather than military occupation.

In settlements such as Lamu and Stone Town (Zanzibar), architectural forms reflect this Arab-African mercantile synthesis. Merchant settlement patterns, mosque patronage, waqf endowments, and guild-based craft production transmitted architectural styles across the Indian Ocean world.[125] Coral-stone houses with interior courtyards, carved wooden doors bearing Arabic inscriptions, and mosque construction techniques reveal Arab influence embedded within African urban society. These features demonstrate not simple transplantation but a locally grounded Arab-Islamic urban order shaped through trade, kinship, and religious institutions.

A vibrant contemporary photo of Lamu or Stone Town architecture, showcasing the carved doors and coral stone. Source: Creative Commons/Flickr.

This mercantile and religious interaction also left a durable linguistic imprint. Linguistically, Kiswahili provides one of the clearest indicators of this synthesis. Swahili is structurally a Bantu language yet incorporates a substantial Arabic lexical component, particularly in domains related to religion, commerce, governance, and literacy.[126] Scholars estimate that Arabic loanwords constitute roughly 20–30 percent of the Swahili lexicon by type frequency, with higher concentrations appearing in formal, religious, and administrative registers; broader estimates approaching 40 percent often reflect expanded corpus classification or historical layering rather than everyday speech usage.

Building on this mercantile and religious foundation, Swahili evolved from a coastal trade language into a dominant regional lingua franca. Its historical role across East and Central Africa is closely linked to its development within Indian Ocean trade networks and Islamic scholarly traditions.[127] From the nineteenth century onward—and especially under colonial and postcolonial state formation—Swahili expanded far beyond the coast into the hinterland, becoming a language of administration, military organization, education, and national integration.[128] Today it is widely spoken across Kenya and Tanzania as a national language, functions as an official language of the East African Community, and in Uganda serves as the official language of the military while being promoted and taught in schools as part of national language policy.[129] Its expansion reflects not only commercial prestige but also its institutional adoption by modern East African states.

This same network of trade, settlement, and institutional adoption also shaped everyday social practice. Culinary diffusion followed the maritime routes, merchant communities, and kinship ties that structured Indian Ocean exchange. Dishes such as pilau, biryani, samosas, and chapati not only illustrate historical Arab and wider Indian Ocean influence but remain staples of contemporary East African cuisine across Kenya, Tanzania, and coastal Uganda. These foods are prepared in both urban and rural households, served at public ceremonies, and integrated into national culinary identity. Jessica B. Harris describes the Swahili culinary tradition as a product of layered maritime exchange networks, a legacy that continues to shape food culture in East Africa today.[130]

5.3 Islam’s Enduring Institutional Presence

Beyond urban form, language, and everyday practice, the most far-reaching legacy of Arab-linked exchange networks was religious institutionalization. Islam spread into West Africa through trans-Saharan trade and into East Africa through maritime commerce. Over time, it became embedded in political authority, legal systems, educational institutions, and social organization.

Mosque architecture in Timbuktu, Jenne, Kilwa, and Lamu reflects regional adaptation of Islamic forms. The growth of Qurʾanic schooling and manuscript culture, particularly in centers such as Timbuktu, was institutionalized through scholarly complexes like Sankore, Sidi Yahya, and Djinguereber. These institutions produced jurists, theologians, and scholars such as Aḥmad Bābā al‑Timbuktī (1556–1627), whose writings circulated across North and West Africa. Surviving manuscript collections—numbering in the hundreds of thousands—attest to sustained intellectual production in theology, jurisprudence (fiqh), astronomy, mathematics, and medicine. More significantly for contemporary Africa, the Maliki legal tradition cultivated in these centers continues to inform Islamic judicial practice in parts of Mali, Niger, and northern Nigeria, while institutions such as the Ahmed Baba Institute in Timbuktu preserve and digitize manuscript collections that remain central to regional scholarly identity and heritage preservation initiatives.[131]

These intellectual centers were and are themselves products of an earlier phase of religious transmission. Early Islamic diffusion between the eighth and fifteenth centuries occurred primarily through Arab merchant networks, elite conversion, and the gradual embedding of Islamic jurisprudence rooted in Arabic legal and theological traditions within ruling courts and urban centers.[132] This phase represented the transmission of Arab-Islamic religious scholarship, legal vocabulary, and scriptural literacy into African political societies.[133] By contrast, from the seventeenth to nineteenth centuries, Sufi brotherhoods (ṭuruq), including the Qadiriyya and Tijaniyya orders whose intellectual genealogies traced back to Arab and North African centers, expanded along commercial routes and facilitated trans-regional religious networks.[134] These brotherhoods functioned not only as spiritual communities but also as mechanisms of social organization, dispute mediation, education, and moral regulation.[135] Their influence remains visible today in West African religious leadership structures, pilgrimage networks, communal arbitration practices, and the continued prominence of Sufi affiliations in Senegal, Mali, Niger, northern Nigeria, and parts of Sudan, demonstrating that the Arab-Islamic religious framework transmitted through earlier exchange networks continues to shape African religious life and social organization.[136]

Islam in Africa was neither uniform nor imposed solely through conquest; it diffused through Arab commercial networks, settlement patterns, elite adoption, scholarly exchange, and gradual social integration. What began as religious transmission became a durable civilizational framework. Today, Islamic jurisprudence informs aspects of family law and dispute mediation in several African states; Qurʾanic schooling remains foundational in many communities; Friday congregational worship structures weekly urban rhythm; pilgrimage networks connect African societies to the wider Muslim world; and Sufi affiliations continue to shape religious authority and communal organization across the Sahel and the Swahili coast. These enduring practices demonstrate that Islam constitutes one of the most sustained and visible legacies of Arab engagement with Africa, embedded not only in belief but in law, education, social norms, and public life.

5.4 Long-Term Economic and Social Continuities

Just as religious and institutional structures endured, earlier patterns of commercial integration also persist in contemporary economic geography. Major port cities such as Casablanca, Dakar, Mombasa, and Dar es Salaam occupy positions shaped by Indian Ocean and trans-Saharan exchange systems established and standardized by Arab authorities and systems centuries earlier. While modern trade operates within global capitalist frameworks distinct from medieval commerce, these geographic corridors of connectivity demonstrate structural continuity in orientation and external linkage.

Social hierarchies on the Swahili coast historically incorporated claims to Arab or Persian ancestry (e.g., Shirazi and Waungwana identities), which were associated with mercantile credibility, urban authority, and access to Indian Ocean trade networks.[137] Rooted in earlier commercial integration, these identity formations shaped patterns of property ownership, marriage alliances, and mercantile partnership that structured coastal economies. Although reconfigured under colonial and postcolonial administrations, elements of these historical status distinctions persist in contemporary coastal political culture, heritage tourism economies, and diaspora-linked trade relations, demonstrating continuity between earlier Arab-linked commercial systems and aspects of present-day East African economic life.[138]

This economic continuity is further reinforced at the level of physical infrastructure. The persistence of Arab-era commercial geography remains visible in the continued centrality of precolonial trade corridors consolidated through Arab-Islamic market systems.

In North Africa, trans-Saharan pathways once linking Mediterranean entrepôts to Sahelian markets were organized around caravan stages, oasis provisioning, and customs regimes. These routes continue to influence modern transport orientation. Contemporary highways, border posts, and logistics nodes frequently track older axes connecting Morocco and Algeria to Mali and Niger, and Libya to the central Sahel.[139]

In East Africa, a similar pattern is observable. The port hierarchy and inland corridors shaped through Indian Ocean commerce anchored in coastal hubs such as Mombasa and Zanzibar extended historically into interior markets. Today, under contemporary capitalist economies, these same corridors remain structurally relevant. The Northern Corridor (Mombasa–Kampala and onward) and related routes function as primary arteries for regional trade, customs transit, and containerized supply chains.[140]

These continuities do not imply unchanged institutions. Rather, they demonstrate that the spatial logic of Arab-linked exchange coastal gateways, caravan-to-hinterland linkages, and corridor-based market integration—continues to shape where trade concentrates and how goods move across African regions today.

In Conclusion

A Millennium That Reconfigured a Continent

The pathways traced across this study from early Arab merchant settlements on the Swahili coast to military conquest and migration in North Africa, from the consolidation of caravan corridors and maritime highways to the institutional embedding of Islamic jurisprudence, and from the scaling of commercial systems to their appropriation under European imperialism demonstrate that Arab engagement was neither episodic nor peripheral. It was transformative. It reshaped spatial orientation, standardized exchange mechanisms, altered linguistic landscapes, institutionalized religious authority, and reconfigured patterns of urban life across multiple African regions.