Why Africa Was Not Colonized Sooner, Truth Behind the Delay!

Why Africa Was Not Colonized Sooner, Truth Behind the Delay!

A Comprehensive Research Analysis.

Introduction:

The Paradox of Proximity and Delay

The historical timeline of European engagement with Africa presents a striking paradox: centuries of sustained contact and proximity coexisted with a prolonged absence of large-scale European territorial conquest. From the early fifteenth century, Portuguese caravels charted the West African coast, establishing fortified trading posts such as São Jorge da Mina (Elmina) by 1482.[1]

Over the next three and a half centuries, Dutch, British, French, Danish, and Brandenburg‑Prussian traders and chartered companies joined this coastal enterprise, becoming deeply embedded in networks of trade involving gold, ivory, and other commodities—most catastrophically, the transatlantic slave trade. Yet until the final quarter of the nineteenth century, European territorial control remained largely confined to isolated forts, a small number of settler colonies (notably the Cape Colony), and the contested territory of Algeria. For much of this period, the vast interior of the continent—often labeled the “Dark Continent” in European discourse, a term reflecting European ignorance rather than African realities—remained beyond sustained European administrative control.

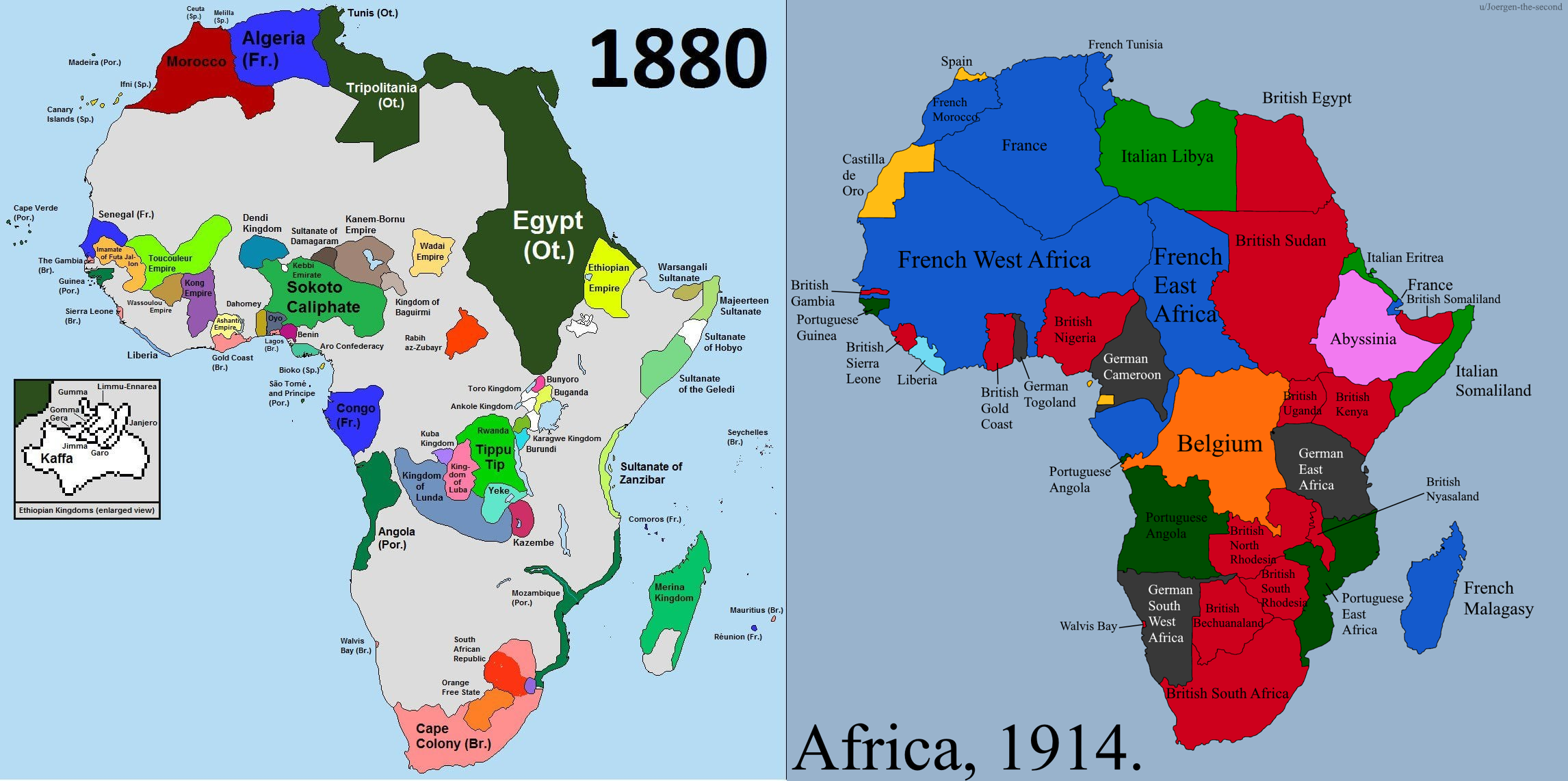

A juxtaposed map. Left: "Africa in 1880" showing minimal European territorial claims (coastal strips, Algeria, Cape Colony). Right: "Africa in 1914" showing the continent almost entirely partitioned into European colonies. Source: Historical atlas.

This situation changed with remarkable speed between roughly 1880 and 1914, during the period known as the Scramble for Africa, following key catalysts such as the Berlin Conference and a series of technological and medical breakthroughs that transformed European capacity for inland expansion. Through a combination of diplomacy, coercive treaties, and devastating military campaigns, European powers divided and occupied approximately ninety percent of the continent.[2]

This study examines the factors that sustained African political autonomy for more than four centuries of sustained European contact. It then asks what changed in the late nineteenth century to make rapid territorial conquest not only possible but seemingly urgent for European states.

The study makes a case that the delay in colonization was not the result of African passivity or European disinterest, but rather the outcome of a dynamic balance between African agency and European limitations. This balance was ultimately overturned by a convergence of technological, medical, economic, and political transformations originating in Europe—most notably advances such as quinine prophylaxis and steam-powered transport—which together reshaped the global conditions under which imperial expansion became feasible and aggressively pursued.

Chapter 1:

The Formidable Fortress — Geographic, Climatic and Health Barriers.

For early European explorers and would-be colonizers, Africa presented a constellation of natural barriers so lethal that nineteenth-century Europeans—particularly in British West Africa—came to describe the region in their own discourse as the “White Man’s Grave.”[3] Long before organized imperial conquest was conceivable, geography, climate, and disease combined to impose extraordinary human costs on European presence, severely constraining the depth, duration, and scale of inland penetration.

1.1 The Disease Wall: Malaria and Beyond

The single greatest barrier to sustained European expansion into Africa was disease. Sub-Saharan Africa was—and remains—home to a dense ecology of tropical pathogens for which Europeans possessed neither immunity nor effective cures during the early modern and much of the nineteenth century. Malaria, transmitted by the Anopheles mosquito, proved the most lethal of these diseases and constituted the primary cause of European mortality. Contemporary estimates suggest that mortality rates for Europeans stationed along the West African coast frequently ranged between 50 and 75 percent within the first year of residence.[4]

Historian John Iliffe observes that in the early nineteenth century British troops deployed in West Africa—primarily in peacetime garrison conditions rather than active campaigns—suffered an annual mortality rate of approximately 483 deaths per 1,000 men, the highest recorded for any region in the world.[5] Under such epidemiological conditions, long-term settlement or large-scale inland military expeditions were not merely difficult but often tantamount to suicide.

The disease barrier, however, extended well beyond malaria alone, encompassing a wider constellation of secondary but equally debilitating diseases. Yellow fever, another mosquito-borne viral disease, periodically swept through coastal and riverine settlements, producing sudden outbreaks marked by high fever, jaundice, internal hemorrhaging, and extremely high fatality rates among non-immune adults.

Sleeping sickness (human African trypanosomiasis) was also among the diseases forming the disease wall, transmitted by the tsetse fly endemic to rainforests and wooded savannas, inflicted a slow but devastating neurological decline that rendered vast regions effectively inaccessible to sustained European activity.[6]

In addition, dysentery and other waterborne gastrointestinal diseases, rampant in tropical environments with limited sanitation, steadily weakened expeditions even when acute infections did not prove immediately fatal.

Together, the interaction of these diseases created a near-impenetrable medical barrier. River systems that Europeans hoped would serve as highways into the interior were frequently bordered by malarial swamps, while the rainforests they sought to penetrate constituted prime habitat for the tsetse fly. Geography and disease ecology were thus inseparably linked, together forming a lethal defensive system that no European power could overcome with the medical knowledge of the time. This reality was illustrated by the disastrous British Niger Expedition of 1841: of approximately 150 Europeans involved, at least 48 died from disease before the expedition achieved its objectives, a fate so common that it came to define the pre-quinine era of African contact.[7]

As a consequence, European activity in Africa was largely confined to short-term trading missions and rotating garrisons in coastal forts, where survival rates—though still poor—were marginally higher than those encountered inland, a limitation that was further reinforced by Africa’s formidable geographic barriers discussed in the following section.

1.2. Geographical Barriers

For centuries, the interior of Africa remained a blank space on European maps—rumored to hold wealth and opportunity, yet consistently resistant to conquest. Disease made prolonged European presence perilous, but geography and climate deepened that constraint, turning the continent’s interior into terrain hostile to sustained occupation. While Africa’s coastline became increasingly familiar to European traders and navigators, the interior remained shielded by a formidable combination of physical barriers.

Some features like the river system in the interior of Africa promised access on maps but proved instead to be among the greatest obstacles to sustained penetration. Africa’s major river systems, its vast equatorial rainforests and deserts, together, they formed an “inner barrier” that rendered prolonged military campaigns and large-scale settlement logistically unviable until the late nineteenth century.

1.2.1. The Deceptive Highways: Rivers That Led Nowhere

As already noted, on the European maps, Africa’s great rivers—the Congo, the Niger, and the Zambezi—appeared as inviting blue highways, seemingly offering direct routes into the continent’s interior. This perception proved illusory. In practice, far from the coast, these rivers were frequently obstructed by rapids, cataracts, and waterfalls that transformed them into dead ends for European-style transport.

The Congo River offered the most dramatic example. Its lower course was blocked by the Livingstone Falls, a roughly 350‑kilometre series of cataracts descending more than 270 metres. Henry Morton Stanley, who undertook the first major European navigation of the river during his Congo expedition of 1874–1877, described this stretch as the wildest river he had ever encountered.[8] These falls rendered continuous navigation from the Atlantic to the interior impossible and later necessitated the construction of a railway to bypass them. Similarly, the Zambezi River—celebrated by David Livingstone as a potential commercial artery—was found to be riddled with cataracts and shifting sandbanks that made it unreliable for sustained steamer traffic.[9]

Rivers were not in themselves barriers in an absolute sense; rather, they failed to function as the reliable corridors Europeans had imagined. Beyond cataracts, rapids, and waterfalls that rendered navigation impossible, these rivers were also subject to pronounced seasonal fluctuations that periodically transformed riverbanks into malarial swamps or reduced channels to chains of shallow pools. Frederick Moir, an agent of the African Lakes Company, observed in a correspondence later cited by historians that the “fringe of malarial swamp … had been so great a barrier against the exploration and colonization of the interior.”[10]

Without dependable navigable waterways, the cost and difficulty of transporting men, supplies, and equipment inland became prohibitive. What appeared on maps as open doors were, in practice, natural chokepoints guarded by terrain, climate, and disease.

1.2.2. The Green Wall: The Impenetrable Rainforest

Beyond the river barriers lay an even more formidable obstacle: the equatorial rainforest. This “green wall” constituted an environment profoundly alien to European experience—a dense and disorienting mass of vegetation beneath a closed canopy that restricted sunlight, combined with heavy rainfall, difficult terrain, and endemic disease.

Late nineteenth-century observers, particularly in military and medical writings, recognized the rainforests as natural fortifications. In an 1891 assessment of the feasibility of colonizing tropical Africa, Surgeon‑General Sir William Moore noted that “nearly the whole of the central belt of the continent was protected by forests supported by a heavy rainfall.”[11] This landscape could not accommodate wheeled transport or pack animals; the tsetse fly, endemic to forested zones, devastated horses and cattle, eliminating essential components of European logistics. Movement was confined to narrow footpaths, rendering coordinated, large‑scale military operations impracticable.

The military implications of rainforest terrain were illustrated decades later during the First World War in German East Africa. General Jan Smuts, writing during the East African campaign of 1916–1918, described the theatre as a land of “magnificent bush and primeval forest everywhere, pathless, trackless, except for the spoor of the elephant or the narrow footpaths of the natives.” He concluded that the campaign had become “a campaign against nature, in which climate, geography, and disease fought more effectively against us than the well‑trained forces of the enemy.”[12] If a twentieth‑century army equipped with modern logistics struggled so severely, it underscores why nineteenth‑century European forces found sustained conquest of rainforest regions logistically impossible.

1.2.3. Deserts and Savannas:

Far from forests and rivers, Africa’s deserts and savannas posed additional constraints, with deserts functioning as near‑absolute barriers to movement and survival, and savannas operating as conditional barriers shaped by distance, water scarcity, and seasonality. The Sahara in the north and the Kalahari in the south constituted vast, arid barriers defined by scarce water, extreme temperatures, and immense distances. Although savanna regions were comparatively more open, they presented their own difficulties: extended supply lines, seasonal droughts, and intense competition for resources between expeditionary forces and local populations.

Without accurate maps, reliable guides, or effective systems of communication, mounting sustained campaigns into the interior remained a logistical impossibility. In savanna and desert zones, long distances between water sources, exposure to extreme heat, and the fragility of supply lines magnified these constraints. The disastrous British Niger Expedition of 1841—intended to promote Christianity and commerce—demonstrated this reality starkly as approximately 150 Europeans involved, 48 died before the expedition achieved its objectives.[13] Such failures were not anomalies but symptoms of structural environmental constraints.

For decades therefore, the African interior remained effectively beyond European control and can conclusively say that early European engagement with Africa was shaped less by political ambition than by structural constraint, as geography, climate, and disease conspired to limit the reach of European power.[14] Until these obstacles could be reduced or circumvented, sustained territorial conquest of the interior was not a realistic possibility.

Deserts, rivers, and rainforests imposed severe logistical limits, while endemic diseases inflicted mortality levels incompatible with permanent occupation or large‑scale military campaigns. European imperial ambitions were thus largely confined to the coast not for lack of intent, but for lack of capacity.

Yet environmental constraints alone do not fully explain the persistence of African autonomy. The conditions that restricted European movement inland also shaped the form of European engagement that followed. Rather than retreating from the continent, European powers adapted by concentrating their presence in coastal enclaves—fortified trading posts that depended on African political authority, military protection, and existing inland networks.[15]

Within this constrained balance of power, African societies were not passive bystanders but active actors, exercising control over trade, diplomacy, and access to the interior.[16] It is this interaction between European limitation and African strength that frames the analysis in the following chapter.

Chapter 2:

Societies of Strength – African Political and Military Resistance

Contrary to late nineteenth‑century European imperial propaganda, particularly that produced within metropolitan political, missionary, and commercial discourse, Europeans did not encounter a political vacuum upon their arrival in Africa.[17] Instead, they engaged with a continent composed of diverse, organized, and often militarily formidable societies that actively shaped—and frequently constrained—the terms of European interaction.

2.1 Sophisticated States and Diplomacy

To portray Africa as a continent of scattered tribes awaiting European mastery is to fundamentally misread history, a misconception that became dominant in late nineteenth- and early twentieth-century European colonial scholarship and popular discourse.[18] Prior to formal colonization, much of Africa was governed by sophisticated polities characterized by centralized authority, codified systems of governance, established diplomatic protocols, and professional military institutions. These political systems were not rudimentary or transitional forms; they were durable engines of statecraft that compelled European powers to engage African rulers for centuries as diplomatic partners, commercial rivals, or military adversaries rather than as passive subjects.

2.1.1 The Kingdom of Kongo (c. 1390–1914)

When Portuguese navigators reached the Kongo coast in the late fifteenth century, they encountered not a political void but a centralized Christian monarchy with a complex administrative apparatus. The Kingdom of Kongo possessed a provincial governance system, recognized legal norms, and a monetized economy that facilitated long-distance trade. Authority was vested in the Manikongo (King), whose power extended through appointed provincial governors and tribute-collecting officials.

The Kingdom of Kongo was not simply a “kingdom” in a vague or informal sense, but a centralized and administratively sophisticated monarchy. When the Portuguese arrived in the 1480s, they were received at the royal court in Mbanza Kongo, where authority was exercised through clearly defined offices and territorial jurisdictions.

The relationship that followed, spanning more than two centuries, was primarily one of diplomacy rather than conquest. It involved sustained ambassadorial exchanges, elite kinship alliances forged through intermarriage between Kongolese nobility and Portuguese or Afro‑Portuguese elites, and shifting military partnerships, as both sides sought to advance their interests within Atlantic commercial networks tied to luxury goods and the transatlantic slave trade.[19]

Kongo’s institutional sophistication effectively bound Portugal into a prolonged, complex, and often fraught partnership, rendering direct territorial domination both logistically difficult and politically inefficient until the kingdom was critically weakened from within by the cumulative pressures of sustained external engagement and internal fragmentation.[20]

2.1.2 The Ashanti Empire (1701–1902)

In West Africa, the Ashanti Empire emerged as one of the most powerful and enduring states of the region. Built upon control of gold resources and later participation in Atlantic trade networks, Ashanti power rested on a highly centralized bureaucracy and a formidable military apparatus. Governance was anchored in the authority of the Asantehene (King), who ruled through councils of elders and maintained a centralized treasury that regulated tribute, trade, and judicial affairs.

The Ashanti military was not an ad hoc force but a professional institution organized into specialized divisions—such as the Adonten (advance guard), Nifa (right wing), Benkum (left wing), Kyidom (rear guard), and the central Gyase corps—under clearly defined command hierarchies, with established logistical support systems and rudimentary medical services.[21]

This institutional strength explains the protracted nature of Anglo-Ashanti conflict. Between 1823 and 1900, Britain fought nine distinct wars against the Ashanti state, each representing a costly campaign against a resilient and adaptive adversary, an exceptional pattern when contrasted with most other British colonial campaigns of the nineteenth century. Conquest was not achieved through a single decisive encounter but through a gradual, piecemeal dismantling of Ashanti political and military institutions—a process only completed at the turn of the twentieth century, when technological asymmetry finally tilted the balance decisively in Britain’s favor.[22]

2.1.3 The Ethiopian Empire

Ethiopia offers perhaps the most striking illustration of African state resilience in the face of European imperialism, distinguished by its sustained sovereignty, diplomatic parity with European powers, and a decisive battlefield victory over a modern colonial army. As a Christian empire with ancient roots, Ethiopia possessed a feudal political structure, a unifying national church centered on the Ethiopian Orthodox Tewahedo tradition, and a long-standing tradition of diplomatic engagement with European powers extending back to the medieval period.[23] Its political authority was reinforced by a geography of mountainous strongholds that functioned as natural fortifications.

Ethiopia was not a loose collection of autonomous communities but an imperial state capable of mobilizing large armies, coordinating regional elites, and negotiating strategically with foreign powers. The decisive Ethiopian victory over Italian forces at the Battle of Adwa in 1896 was therefore not accidental, but was underpinned by the large-scale mobilization of an estimated 80,000–100,000 Ethiopian troops, many armed with modern rifles acquired through sustained arms imports from France, Russia, and other European suppliers.[24]

That victory was an outcome of Emperor Menelik II’s deliberate program of state consolidation, military modernization, and diplomatic maneuvering within a competitive European imperial environment.

The defeat of Italy at Adwa demonstrated to Europe that certain African polities remained sufficiently entrenched, strategically sophisticated, and militarily capable to resist colonization—even against modern European armies—well into the late nineteenth century[25], thereby underscoring the presence of powerful African states as a central structural reason why large-scale European colonization of the continent had been delayed for centuries.

A portrait of Asantehene (King) Osei Bonsu and a photograph of Ashanti sika dwa (Golden Stool) regalia. A symbol of Ashanti state power and sovereignty, which they fought multiple wars to protect from the British.

2.2 Military Parity and Strategic Agency

With the presence of durable and centralized African polities already established, this section turns to the military and strategic conditions that further constrained early European expansion. The presence of powerful states alone does not fully explain the delayed colonization of Africa; it must be paired with an understanding of military parity and African strategic agency that prevailed well into the nineteenth century.

2.2.1 Arms, Strategy, and the Balance of Power

Until the mid-nineteenth century, the military technological gap between African and European forces was not decisive, as demonstrated in repeated encounters in which African armies matched or defeated European expeditions, including Ethiopian victories culminating at Adwa and earlier reverses suffered by European forces in West and Southern Africa.[26]

African armies were often large, tactically sophisticated, and increasingly well-armed. Through sustained engagement in coastal and trans-Saharan trade networks, many African states—particularly in West Africa—acquired substantial quantities of firearms, including muskets and later rifles, while polities in the Horn of Africa supplemented local production with imported modern weapons, thereby maintaining a relative balance of power.[27]

Military capability, however, was only one dimension of resistance. African rulers were also astute strategic actors who actively shaped diplomatic and commercial relationships to preserve autonomy and limit European encroachment.

2.2.2 Playing European Rivals Against Each Other

African rulers frequently granted trade privileges, diplomatic recognition, or limited military concessions to one European power in order to counterbalance the influence of another, a strategy employed in many African communities including Ethiopia, West African coastal states such as the Asante and Dahomey, as well as by North African regencies navigating rival European interests.[28] This strategy allowed African leaders to preserve room for maneuver within an increasingly competitive imperial environment rather than submit to unilateral domination.

In Ethiopia, during the late nineteenth century, Emperor Menelik II carefully balanced relationships with competing European powers, including France, Italy, and Britain. He secured modern weapons, political recognition, and technical advisors from each, while deliberately exploiting their rivalries in the Horn of Africa. This diplomatic triangulation proved central to Ethiopia’s military modernization and its ability to resist Italian colonial claims, culminating in the decisive Ethiopian victory at the Battle of Adwa in 1896.[29]

2.2.3 Controlling Access to the Interior as Gatekeepers

Beyond diplomacy and warfare, many coastal and strategically located African polities exercised power by controlling access between the interior and the coast, a form of gatekeeping that constrained European movement, delayed territorial penetration, and limited the feasibility of sustained inland conquest. These states functioned as indispensable intermediaries, regulating the flow of commodities, information, and people between inland regions and global trade networks.

The Sultanate of Zanzibar provides a clear illustration of this gatekeeping role, grounded in its centralized regulation of caravan commerce, taxation, and political authority along the East African coast.[30] Under Sultan Sayyid Said (r. 1806–1856) and his successors, Zanzibar emerged as the dominant commercial power along the East African coast. The sultanate did not merely participate in trade; it organized, supervised, and taxed the caravan routes penetrating the interior (the nyika), particularly those associated with the ivory trade. European merchants and explorers—including Richard Burton and John Hanning Speke—were dependent on the Sultan’s permission, porters, and guides to travel inland.[31] This control over access enabled Zanzibar to shape the pace, direction, and limits of European penetration well before the advent of formal colonial rule.

2.3 Treaties – Vehicles of Direct Delay of Colonization by African Societies.

As the preceding sections have shown, African resistance to early European expansion extended beyond battlefield confrontation and military parity. Alongside armed strength and strategic diplomacy, African rulers also employed legal and treaty-based mechanisms as deliberate instruments of statecraft, using them to constrain European ambitions and delay the consolidation of formal colonial rule.

2.3.1 A Form of Legal and Diplomatic Resistance

African rulers were not naïve victims signing away their land or sovereignty. They were strategic political actors who engaged Europeans through their own legal concepts and diplomatic traditions while seeking to preserve core authority. Treaties were often interpreted by African leaders not as permanent transfers of sovereignty, but as conditional alliances, agreements of friendship, or limited leases of access and use.[32]

By construing treaties in this manner, African rulers retained ultimate control over land and governance. European powers were therefore compelled to continue negotiating, renewing terms, and providing gifts, tribute, or military assistance in order to sustain these relationships, rather than asserting immediate territorial domination.[33] This process significantly slowed the transition from commercial engagement to formal colonial rule.

2.3.2 A Source of Enduring and Costly Conflicts

When European authorities later attempted to assert full ownership over land based on their own legal interpretations of treaties, African leaders frequently rejected these claims, citing breaches of the original agreements. Such disputes over meaning and authority did not remain abstract legal disagreements; they escalated into armed conflict, uprisings, and prolonged confrontations that imposed heavy costs on colonial powers.[34]

The conflicts between the British and the Xhosa polities in southern Africa—commonly referred to as the Xhosa Wars, which spanned much of the nineteenth century—were fueled by precisely these disagreements over land treaties and sovereignty.[35] Each successive conflict required extensive military expenditure, repeated campaigns, and long-term administrative commitment, collectively slowing the pace and increasing the cost of colonial expansion in the region.

2.3.3 A Hinderance to “Effective Occupation” for Decades

In many cases, European powers emerged from treaty negotiations with written claims of land purchase or protection, yet on the ground African authorities continued to administer territory according to their own political systems and customary laws. This gap between paper sovereignty and actual control represented a significant obstacle to European ambitions until the late nineteenth century, a condition that later imperial policymakers sought to resolve through the doctrine of "effective occupation" formalized at the Berlin Conference (1884–1885).[36]

As a result, European states were often unable to administer, tax, or settle territories that they claimed through treaties. Effective colonial occupation required undisputed authority and sustained presence—conditions that ambiguous treaty arrangements consistently failed to deliver. The persistence of African governance structures therefore delayed the realization of colonial control despite nominal European claims.

This dynamic provides further evidence in support of the argument developed under military parity and strategic agency. African resistance was not confined to armed confrontation; it also included sophisticated legal and diplomatic maneuvering that exploited divergent understandings of sovereignty and land tenure to preserve political autonomy.

2.3.4 Resisting Unfavorable Treaties

African leaders did not passively accept treaties that threatened their sovereignty. They frequently challenged, reinterpreted, or repudiated imposed agreements, drawing on alternative legal frameworks and concepts of land ownership to defend their authority.

The Treaty of Wuchale (1889) between Ethiopia and Italy offers a prominent illustration.[37] The ensuing diplomatic crisis arose from a discrepancy in Article 17: the Amharic version granted Emperor Menelik II the option to employ Italian diplomats for foreign affairs, whereas the Italian version rendered this arrangement obligatory, effectively establishing a protectorate. Upon discovering the mistranslation, Menelik formally rejected the treaty in 1893, invoking its legal invalidity to nullify Italian claims and mobilize both domestic and international support.

In a nutshell, these powerful and sophisticated forms of resistance mounted by Africa’s diverse polities, as detailed throughout this chapter, constituted fundamental pillars of the truth behind the delay of Africa’s colonization. Far from being passive recipients of European ambition, kingdoms such as Kongo, Ashanti, and Ethiopia engaged European powers for centuries as diplomatic partners and military rivals, leveraging complex bureaucracies, formidable armies, and strategic acumen to shape the terms of interaction.

This agency compelled European states into protracted negotiations, costly wars, and reliance on African intermediaries, delaying conquest until the very late nineteenth century at considerable financial and human cost. Persistent resistance—from early conflicts in North Africa to the Anglo-Ashanti and Anglo-Zulu wars—demonstrates that African societies actively defended their sovereignty and, in doing so, postponed the era of formal colonial subjugation for centuries. Their strength and strategic sophistication were not peripheral to the story of European expansion but central to understanding why the Scramble for Africa only became possible once dramatic shifts in technological and medical power finally undermined these enduring structures of African autonomy as we shall see later.

Chapter 3:

Deconstructing the Myths – Challenging Misconceptions of "Easy Colonization"

Building on the demonstration in the preceding chapter that African societies possessed political strength, military capacity, and legal‑strategic agency—evident in sustained military resistance, complex treaty negotiations, and diplomatic maneuvering— this chapter turns to the ideological frameworks that obscured those realities. Popular understandings of African history have long been filtered through colonial narratives designed to justify conquest by distorting or erasing pre‑colonial African social and political organization.

3.1 The Myth of the "Empty" or "Unorganized" Land

A core tenet of colonial ideology was the doctrine of terra nullius—rooted in Roman law traditions and later adapted in European imperial jurisprudence—the claim that African territories constituted “nobody’s land,” or that their inhabitants lacked recognizable systems of governance or land ownership.[38] This doctrine functioned as a legal and moral fiction rather than an empirical description of African realities.

There is a foundational legal repudiation of terra nullius that appears in the 1975 Advisory Opinion of the International Court of Justice (ICJ) on Western Sahara, which is analytically relevant not as an anachronistic judgment, but as a retrospective clarification of the legal principles that European powers had already implicitly acknowledged in nineteenth‑century colonial practice. The Court was asked directly whether the territory had been terra nullius at the time of colonization and unanimously concluded that it was not, affirming the existence of organized social and political structures among the indigenous populations.[39]

As demonstrated in Chapter 2, European powers were repeatedly compelled to negotiate with kings, chiefs, councils, and other recognized authorities. The very existence of thousands of treaties—however coercive, unequal, or misunderstood—constitutes evidence that Europeans acknowledged African political legitimacy. The Berlin Conference of 1884–1885, which formalized European colonial claims, further codified this recognition through the principle of “effective occupation,” requiring colonial powers to demonstrate treaties with local rulers and establish administrative presence to validate claims. [40] The persistence of the terra nullius myth thus served primarily to legitimize land seizure and the imposition of foreign rule rather than to reflect historical reality.

3.2 Colonial Propaganda and the "Civilizing Mission"

The late nineteenth‑century push for colonization was presented to European publics as a benevolent “Civilizing Mission,” promoted through missionary school textbooks, colonial exhibitions such as the Paris Exposition of 1889, and popular imperial literature (mission civilisatrice in French discourse and the “White Man’s Burden” in Anglo‑American contexts).[41] This ideological frame, disseminated through newspapers, popular literature, missionary writings, and colonial exhibitions, portrayed Africans as childlike, savage, or stagnant, requiring European intervention through Christianity, commerce, and governance.

Such representations systematically erased the histories of powerful kingdoms, complex trade networks, and intellectual traditions that had long structured African societies. Conquest was reframed as a moral obligation rather than a political and economic choice, while the violence of military pacification and the extraction of labor and resources were concealed beneath humanitarian rhetoric.[42]

3.3 The Persistence of the Narrative

These colonial framings have proven remarkably durable, continuing to surface in contemporary school curricula, popular documentaries, and mainstream media representations of African history. In Western education systems and popular media, the Scramble for Africa is frequently depicted as an inevitable and almost natural consequence of European progress, with African resistance minimized or portrayed as futile. The long centuries of African autonomy, negotiation, and parity preceding formal colonization are often glossed over or omitted entirely.[43]

Challenging this narrative requires centering African agency, a corrective that not only reframes the Scramble itself but also sets the stage for the next analytical chapter, which examines how European powers ultimately restructured imperial strategy in response to sustained African resistance, as a substantial body of scholarship has done, and recognizing that the rapidity of conquest in the late nineteenth century reflected not inherent African weakness but the sudden emergence of overwhelming technological and medical asymmetries associated with the Industrial Revolution.[44] Reframing the Scramble in this way restores African societies to their rightful place as historical actors whose resistance meaningfully shaped the timing, form, and costs of European imperial expansion.

Chapter 4:

The European Catalyst – Tilting the Balance, Finally Colonizing Africa.

As the preceding chapters have shown, the prolonged delay in the colonization of Africa was shaped by the interaction of African political strength, military parity, diplomatic agency, and legal resistance with formidable natural barriers—disease environments, climate, deserts, and savannas—which together produced a durable equilibrium of power that constrained sustained European penetration and settlement.

This equilibrium, however, was ultimately disrupted by a cluster of transformations originating within Europe itself. Advances emerging from European factories, laboratories, and financial institutions altered both the feasibility and desirability of conquest. The Industrial Revolution not only supplied the technologies that made large-scale territorial domination possible but also generated economic pressures that rendered imperial expansion increasingly attractive by the late nineteenth century.[45]

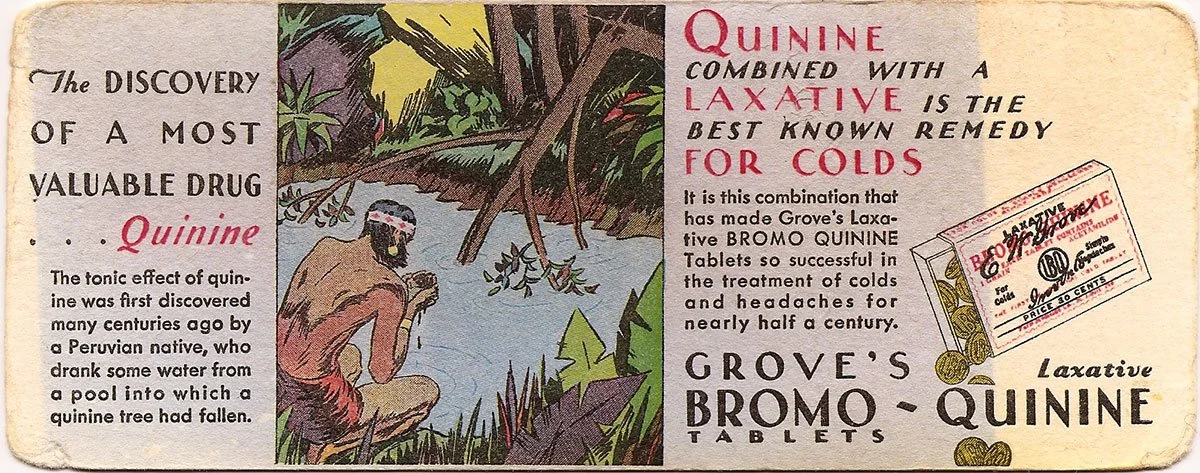

4.1 The Medical Breakthrough: Quinine Prophylaxis

The single most consequential technological factor in this transformation was quinine.[46] Isolated from cinchona bark in the 1820s and systematized as a prophylactic by the 1850s, quinine provided the first effective defense against malaria. Although not a cure, it dramatically reduced European mortality rates in tropical Africa. For the first time, administrators, soldiers, and settlers could realistically imagine surviving long-term inland postings. The 1854–1856 expedition of the Niger River led by William Balfour Baikie, during which quinine was administered regularly to the crew and no deaths were recorded, stands as a symbolic turning point in European penetration of the African interior.[47]

The history of quinine—from a localized Andean remedy to a standardized pharmaceutical tool of empire—spans centuries of cross-cultural exchange, scientific experimentation, and colonial ambition. While its earliest origins are obscured by time, historical evidence indicates that Indigenous communities in the Andes of present-day Peru used cinchona bark to treat ailments associated with chills and fevers. European awareness of the bark began in the early seventeenth century, when Jesuit missionaries in Peru observed its medicinal use and transported it to Europe by the 1630s, where it became known as “Jesuit’s Bark.” For nearly two centuries, European physicians relied on crude bark preparations with uneven and often unreliable results.

A decisive shift occurred in 1820, when French chemists Pierre-Joseph Pelletier and Joseph-Bienaimé Caventou successfully isolated the active alkaloid quinine. This laboratory breakthrough transformed quinine from an inconsistent folk remedy into a standardized and potent pharmaceutical, enabling its systematic deployment. As European expansion intensified in malaria-endemic regions of Africa and Asia, access to reliable quinine supplies became a strategic necessity.

This necessity triggered what historians have described as a quinine “arms race,” rooted in imperial botany and the global transplantation of cinchona.[48] Britain, France, and the Netherlands launched expeditions—often involving clandestine seed transfers—to secure cinchona plants from South America and establish plantations in colonial territories such as India and Java.

By the 1850s, the prophylactic use of standardized quinine had been refined and widely adopted. Baikie’s Niger expedition demonstrated its transformative impact: by administering regular doses of quinine to his crew, he completed the journey without a single malaria fatality, an unprecedented achievement that contemporaries and later historians alike identified as a symbolic rupture in the long-standing biological barrier to European conquest.[49] Quinine thus evolved from a local Andean remedy into a technological keystone of nineteenth-century imperialism.

A historical advertisement or medical kit from the late 19th century featuring quinine pills or tonic. "Quinine: The 'Miracle' Drug that Opened the African Interior to European Colonization.”

4.2 The Tools of Conquest: Steam, Rail, and the Gun

Medical advances alone did not enable conquest; they operated alongside the ideological frameworks discussed in Chapter 3, which legitimated expansion by portraying domination as necessary, lawful, and civilizing. They were complemented by a suite of technological innovations that revolutionized transportation, communication, and warfare.

Steam-powered vessels marked one of the earliest transportation breakthroughs to alter European access to Africa’s interior. Introduced along African coasts and major rivers from the early nineteenth century, steamships could navigate upstream against strong currents and operate independently of wind, overcoming the limitations that had long constrained sailing vessels. River systems such as the Niger, Congo, and Zambezi were gradually transformed into navigable corridors for exploration, commerce, and military projection, significantly easing European penetration of inland regions.[50]

Railway construction followed later in the nineteenth century and addressed the remaining logistical barriers to sustained territorial control. Beginning in the 1870s and accelerating after the 1880s, European powers extended rail lines from coastal enclaves into the interior, enabling the rapid movement of troops, heavy equipment, and supplies. Projects such as the Dakar–Sudan railway in West Africa and the Mombasa–Uganda railway in East Africa resolved the long-standing problem of overland transport across vast distances, making permanent occupation and administrative control increasingly feasible.[51]

Advances in communication further centralized imperial control. The telegraph allowed colonial administrators to relay information and coordinate military campaigns with metropolitan governments in near real time, reducing delays and increasing administrative coherence across empire.

Most decisively, as military historians have emphasized, the military balance shifted during the mid- to late nineteenth century with the introduction of breech-loading rifles, repeating firearms, and, above all, the Maxim gun, patented in 1884. These weapons dramatically increased European firepower and lethality. Encounters such as the 1898 Battle of Omdurman, in which British-Egyptian forces armed with Maxim guns killed thousands of Mahdist Sudanese fighters, epitomized the emergence of a new and profoundly asymmetrical form of warfare.[52]

4.3 The Economic Imperative: Capital, Markets, and Raw Materials

Technological superiority coincided with mounting economic pressures within Europe, intensifying the structural incentives for overseas expansion identified by economic historians. The Long Depression of 1873–1896 generated falling prices, shrinking profits, and chronic industrial overcapacity.[53] In response, European states increasingly adopted protectionist tariffs, limiting access to continental markets and intensifying competition among industrial powers hence Africa being perceived as the last untapped frontier.[54]

This context produced a new economic rationale for imperialism. Colonies offered captive markets in which manufactured goods from the metropole could be sold under preferential tariff regimes, ensuring outlets for surplus production. At the same time, the Second Industrial Revolution generated unprecedented demand for raw materials. Africa came to be viewed not merely as a source of slaves or precious metals, but as a vast reservoir of industrial inputs, including palm oil for machinery lubrication, rubber for tires and electrical insulation, copper for electrical infrastructure, and precious minerals such as diamonds and gold.[55]

Imperial expansion also provided opportunities for surplus capital investment. With returns on domestic ventures declining, European financiers sought high-yield projects abroad. Railway construction, port development, and mining enterprises in Africa offered lucrative prospects for investment. This economic drive increasingly fused with state power, giving rise to the defining instrument of the New Imperialism: state-chartered companies empowered to administer and exploit African territories on behalf of European governments.[56]

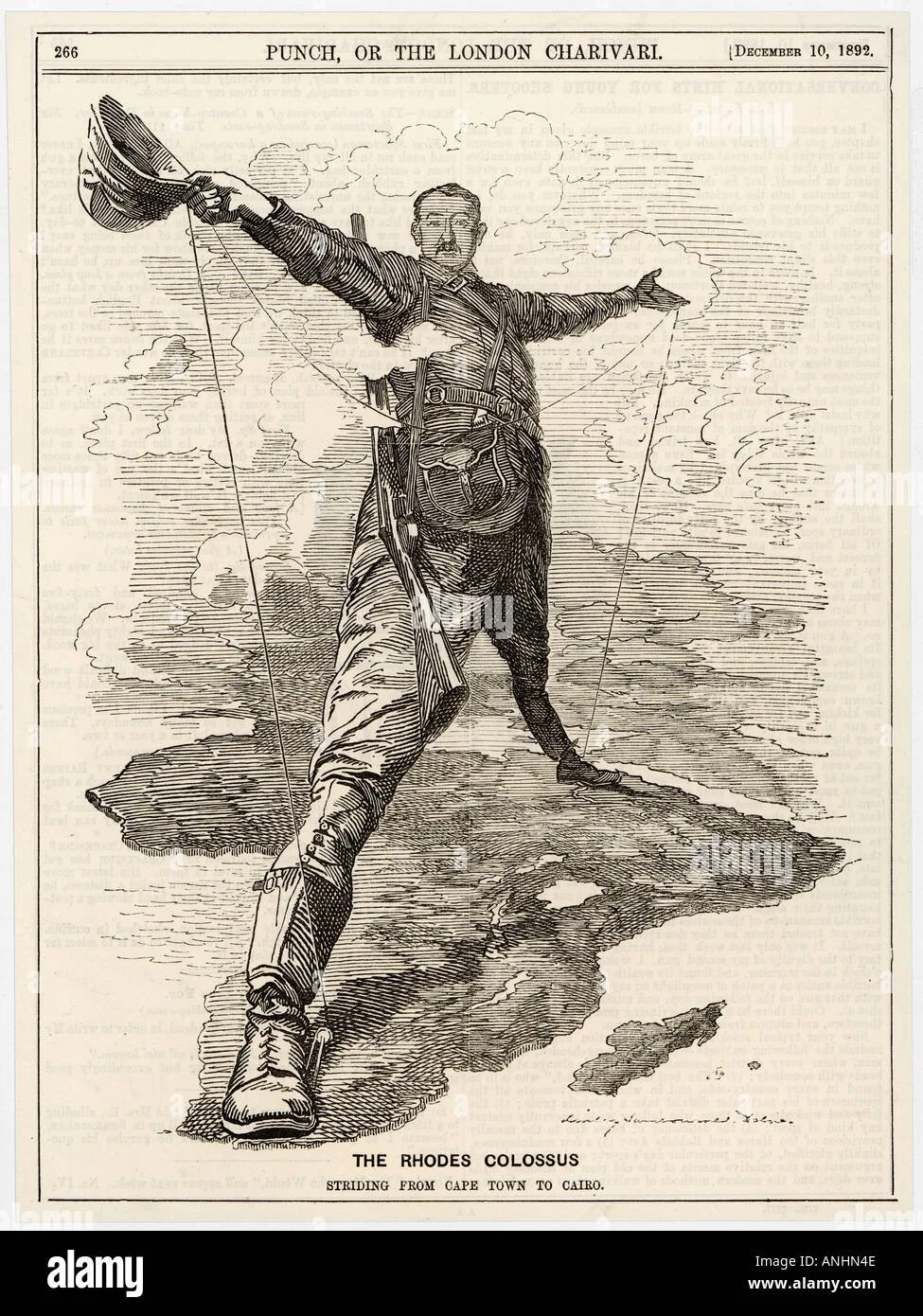

This phase of imperial expansion was driven less by individual traders than by the coordinated interests of finance capital, chartered companies, and metropolitan states.[57] Entities such as Cecil Rhodes’s British South Africa Company exemplified this fusion of private capital and political authority, marking a decisive shift in the scale, organization, and intensity of European colonial rule in Africa.

Chapter 5:

The Final Trigger – Political Turning Points and the Scramble (1880-1914)

Building on the technological, medical, economic, and ideological transformations examined in the preceding chapter, this section analyzes the political mechanisms that converted European capacity into rapid territorial seizure. Once the equilibrium that had long constrained conquest was broken, a sequence of diplomatic conferences, coercive treaties, and escalating interstate rivalries precipitated the rapid and competitive partition of the African continent.

5.1 The Berlin Conference (1884-85): Making the Rules for African Conquest.

Convened by Otto von Bismarck to manage intensifying European rivalries—particularly in the Congo Basin—the Berlin Conference formalized the procedural framework of the new imperial order. Its most consequential outcome was the codification of the Principle of Effective Occupation, which stipulated that international recognition of territorial claims required demonstrable administrative and military presence rather than symbolic acts such as flag planting or coastal forts alone.[58]

This principle transformed European competition into a literal scramble by overturning the earlier treaty-based ambiguity discussed in Chapter 2: rather than relying on loosely interpreted agreements with African rulers, rival powers now rushed to dispatch treaty agents, soldiers, and administrators into the interior to secure demonstrable control before competitors could do so.[59]

The conference also established international rules governing navigation on major African rivers and proclaimed a nominal commitment to suppressing the slave trade, a provision widely criticized by contemporaries and later historians as largely rhetorical.[60]

The famous cartoon "The Rhodes Colossus" from Punch magazine (1892), showing Cecil Rhodes straddling the continent. Caption: A contemporary visual satire of the aggressive, all-encompassing nature of British imperial ambition during the Scramble.

5.2 The "Treaty-Making" Frenzy and Coercive Diplomacy

Following Berlin, a vast industry of treaty-making unfolded across the continent. European agents—such as Carl Peters on behalf of Germany and representatives of King Leopold II’s International African Association—fanned out across the interior, securing hundreds of agreements with African rulers. These treaties were frequently signed under conditions of coercion, mistranslation, or profound asymmetry of legal understanding. While African leaders often interpreted such agreements as limited alliances or commercial arrangements, European powers treated them as permanent cessions of sovereignty.[61]

These documents functioned as legal instruments in European diplomatic exchanges rather than as reflections of effective authority on the ground, building on earlier African treaty practices discussed in Chapter 2 but now operating under far more coercive and asymmetrical conditions. Nevertheless, they became the juridical foundation upon which territorial claims were mapped and later enforced through military occupation.

5.3 The Domino Effect of Imperial Rivalry

Once the legal ambiguity of treaties gave way to the post‑Berlin requirement of demonstrable control, imperial expansion unfolded within a competitive international system in which the actions of one power compelled responses from others, producing a classic security dilemma.

France, seeking geopolitical recovery after its defeat by Prussia in 1871, pursued an ambitious eastward expansion from Senegal toward Djibouti. Britain, intent on safeguarding routes to India and maintaining dominance from the Cape Colony, envisioned a north–south axis linking Cairo to Cape Town. Germany, newly unified and eager for international prestige, rapidly claimed territories in Togo, Cameroon, German East Africa, and South-West Africa. King Leopold II of Belgium constructed a personal colonial domain in the Congo, while Portugal attempted to revive historic claims connecting Angola and Mozambique.[62]

These overlapping ambitions repeatedly produced diplomatic crises and military flashpoints—most clearly exemplified by the Fashoda Incident of 1898, in which British and French forces confronted one another on the Upper Nile over competing visions of continental dominance—illustrating how the advance of one imperial power compelled reactive expansion by others, transforming Africa into the primary arena of an escalating security dilemma. Such confrontations accelerated the pace of conquest, as European powers rushed to consolidate claims before rivals could intervene.

5.4 Internal African Vulnerabilities

By the late nineteenth century, some African societies faced internal pressures that reduced their capacity to resist sustained external assault. The long-term demographic and political disruptions caused by the transatlantic and Indian Ocean slave trades had destabilized many regions. Environmental crises, including the Great Southern African Drought of approximately 1875–1895, generated famine, population displacement, and intensified conflict over resources. Inter-state warfare and succession disputes—such as those associated with Zulu expansion in southern Africa—further weakened political cohesion in certain areas.[63]

These vulnerabilities, however, were secondary rather than causal, as comparable demographic, environmental, and political stresses had existed in earlier centuries without producing continent‑wide conquest—a point emphasized by continental historians who note the persistence of African crises without imperial collapse.[64] They created openings that European powers exploited, but they do not explain the timing of the Scramble itself. The decisive factor remained the externally generated transformation in European capacity and political will analyzed in Chapter 4.

Conclusion:

Synthesis and Legacy

The colonization of Africa was neither inevitable nor the culmination of a continuous European design. It was instead the delayed and abrupt outcome of a specific historical conjuncture in the late nineteenth century. For over four centuries, European powers possessed maritime reach and commercial presence but were constrained by Africa’s disease environments, geography, and the political and military strength of its societies. Under these conditions, large-scale territorial conquest was neither feasible nor necessary.

The Industrial Revolution shattered this equilibrium. Medical advances such as quinine prophylaxis, transportation technologies including steamships and railways, and unprecedented firepower overcame natural and military barriers. Simultaneously, economic transformations generated new imperatives for territorial control, while political mechanisms—formalized at Berlin—converted capacity into action. The result was a rapid and violent partition of the continent.

The legacy of this delayed but accelerated conquest has been profound. Arbitrary borders drawn in European capitals fractured pre-existing political and social systems, producing enduring postcolonial challenges. The extractive economic structures imposed during colonial rule, analyzed by Walter Rodney as the process of underdeveloping Africa, embedded long-term inequalities.[65]

Ultimately, recovering this history restores African societies to their rightful place as active historical agents whose long resistance delayed colonization for centuries and whose eventual subjugation resulted not from inherent weakness but from a late‑nineteenth‑century convergence of European technological, economic, and political transformations.

Endnotes:

[1] John K. Thornton, Early Portuguese Expansion in West Africa: Its Nature and Consequences, in Portugal, the Pathfinder: Journeys from the Medieval toward the Modern World, ed. George D. Winius (Madison: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies, 1995), 121-132.

[2] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (New York: Random House, 1991), xxi–xxiii, 602–605.

[3] Philip D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780-1850 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964), 58. The phrase was commonly used in 19th-century British writings.

[4] Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 1–5, 25–30.

[5] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 191.

[6] Kenneth F. Kiple, ed., The Cambridge World History of Human Disease (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1993), 1094–1097; Maryinez Lyons, The Colonial Disease: A Social History of Sleeping Sickness in Northern Zaire, 1900–1940 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 1–6.

[7] Philip D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780–1850 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964), 291–294.

[8] Henry Morton Stanley, Through the Dark Continent; or, The Sources of the Nile Around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and Down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean (London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1878), vol. 2, 3–25.

[9] David Livingstone, Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries, and of the Discovery of the Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858–1864 (London: John Murray, 1865), 15–18, 523–526.

[10] Frederick Moir, quoted in John McCracken, Politics and Christianity in Malawi, 1875–1940: The Impact of the Livingstonia Mission in the Northern Province (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977), 29–31.

[11] Moore, Sir William. “On the Feasibility of Acclimatization in Tropical Africa.” Journal of the Royal United Service Institution 35, no. 159 (1891): 477-492, p. 480. Moore’s analysis reflects the contemporary European military and medical understanding of the rainforest as a defensive geographical feature.

[12] Smuts, Jan Christiana. Jan Christian Smuts: A Biography. London: Cassell, 1952, pp. 188-189. Smuts’s retrospective analysis, though from a later period, provides a powerful testament to the enduring military-logistical challenge posed by Africa’s rainforest environment, even with modern technology.

[13] Howard Temperley, "The British and American Anti-Slavery Expeditions to the Niger in the Nineteenth Century," The Journal of African History 6, no. 1 (1965): 123-129.

[14] Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), esp. 1–5.

[15] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 35–58.

[16] Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Bogle‑L’Ouverture, 1972), 72–85.

[17] Philip D. Curtin, The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780–1850 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964), 3–32; Basil Davidson, Africa in History: Themes and Outlines, rev. ed. (New York: Touchstone, 1995), 11–29.

[18] Terence Ranger, "The Invention of Tradition in Colonial Africa," in The Invention of Tradition, ed. Eric Hobsbawm and Terence Ranger (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1983), 211–262; John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 193–200.

[19] John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 92–99; John K. Thornton, The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 9–15.

[20] John K. Thornton, The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718 (Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983), 3–15.

[21] Ivor Wilks, Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 326–349.

[22] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: 1876-1912 (New York: Random House, 1991), 448-456.

[23] Taddesse Tamrat, Church and State in Ethiopia, 1270–1527 (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1972), 1–18; Steven Kaplan, The Monastic Holy Man and the Christianization of Early Solomonic Ethiopia (Wiesbaden: Franz Steiner Verlag, 1984), 3–27; Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (London: Heinemann, 1976), 1–22.

[24] Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (London: Heinemann, 1976), 256–262; Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991, 2nd ed. (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), 84–90.

[25] Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991, 2nd ed. (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), 65–71; Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (London: Heinemann, 1976), 283–310.

[26] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 186–194; Jeremy Black, Eighteenth-Century Warfare (Basingstoke: Palgrave Macmillan, 1999), 214–219.

[27] Joseph E. Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 299–325; Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 123–130.

[28] Ivor Wilks, Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 137–165; John Wright, Libya, Chad and the Central Sahara (London: C. Hurst, 1989), 41–58.

[29] Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991, 2nd ed. (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), 65-71. See also Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (London: Heinemann, 1976), 283-310.

[30] Abdul Sheriff, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873 (London: James Currey, 1987), 45–72; Frederick Cooper, Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 15–21.

[31] Jeremy Prestholdt, Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008), 42-68. See also Abdul Sheriff, Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873 (London: James Currey, 1987).

[32] Thomas Spear, "Neo-Traditionalism and the Limits of Invention in British Colonial Africa," Journal of African History 44, no. 1 (2003): 3-27. Spear analyzes how African leaders consciously manipulated "customary" law and their own political traditions as a strategic tool to engage with and resist colonial authority, demonstrating deliberate agency rather than passive acceptance.

[33] John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400-1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 74-81. Thornton details the early diplomatic and commercial relationships between European traders and African rulers, showing that agreements were consistently framed within African political contexts of reciprocity, clientage, and ongoing negotiation, not one-time sales.

[34] Martin Chanock, Law, Custom and Social Order: The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 60-70. Chanock’s seminal work documents how the British colonial legal system itself was forged through these conflicts, as officials struggled to impose European property law on societies that understood land allocation as a revocable grant from a chief or community.

[35] Clifton Crais, The Making of the Colonial Order: White Supremacy and Black Resistance in the Eastern Cape, 1770-1865 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992), 98-112. Crais meticulously traces how conflicting interpretations of land cession treaties were the central, recurring catalyst for each of the first several Xhosa Wars, tying diplomatic misunderstanding directly to prolonged military stalemate

[36] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 203-205. Iliffe provides the broad historical context, arguing that the gap between treaty claims and actual control was the single greatest barrier to European interior expansion until the late 19th century, making "effective occupation" a legal fiction for generations.

[37] Bahru Zewde, A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991, 2nd ed. (Oxford: James Currey, 2001), 74–83; Sven Rubenson, The Survival of Ethiopian Independence (London: Heinemann, 1976), 109–125.

[38] Antony Anghie, Imperialism, Sovereignty and the Making of International Law (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2005), 32–58; Lauren Benton, Law and Colonial Cultures: Legal Regimes in World History, 1400–1900 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 213–230.

[39] General Assembly Resolution 30th Session-www.un.org

[40] The Belgian Congo and the Berlin act, by Keith, Arthur Berriedale, 1919, pg. 52

[41] John M. MacKenzie, Propaganda and Empire: The Manipulation of British Public Opinion, 1880–1960 (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1984), 1–35; Anne McClintock, Imperial Leather: Race, Gender and Sexuality in the Colonial Contest (New York: Routledge, 1995), 20–45; Pascal Blanchard et al., Human Zoos: Science and Spectacle in the Age of Colonial Empires (Liverpool: Liverpool University Press, 2008), 67–92.

[42] Alice L. Conklin, A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 1–22; Edward Said, Culture and Imperialism (New York: Knopf, 1993), 8–15.

[43] Dipesh Chakrabarty, Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 3–23; James H. Sweet, “The Iberian Roots of

[44] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 193–205.

[45] Daniel R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 3–34.

[46] Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 70–102.

[47] Daniel R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (New York: Oxford University Press, 1981), 67-71.

[48] Richard H. Grove, Green Imperialism: Colonial Expansion, Tropical Island Edens and the Origins of Environmentalism, 1600–1860 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 181–215; Londa Schiebinger, Plants and Empire: Colonial Bioprospecting in the Atlantic World (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2004), 145–176.

[49] Philip D. Curtin, Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989), 91–95; Daniel R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 58–60.

[50] Daniel R. Headrick, The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century (Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1981), 11–27; John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 205–208.

[51] Gordon Pirie, “Railways and Colonial Development in Africa,” Journal of African History 26, no. 2 (1985): 175–198; Frederick Cooper, Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 21–24.

[52] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 194–196.

[53] Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Empire: 1875–1914 (London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson, 1987), 34–57; A. G. Hopkins, An Economic History of West Africa (London: Longman, 1973), 121–145; A. G. Hopkins, “The New Imperialism in West Africa,” Past & Present 61 (1973): 141–170.

[54] Frankema, E., Williamson, J.G., & Woltjer, P. (2015). An economic rationale for the African scramble: the commercial transition and the commodity price boom of 1845-1885. NBER Working Paper No. 21213. This economic analysis provides a core rationale, arguing that a sustained commodity price boom for African exports peaked precisely at the time of the Berlin Conference (1884-85), creating a powerful and timely incentive for European powers to secure formal control.

[55] Frederick Cooper, Colonialism in Question: Theory, Knowledge, History (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2005), 33–45.

[56] J. A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1902), 85–110; P. J. Cain and A. G. Hopkins, British Imperialism, 1688–2000 (London: Longman, 2001), 280–318; V. I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916; repr., London: Penguin, 2010), 67–92.

[57] J. A. Hobson, Imperialism: A Study (London: George Allen & Unwin, 1902), 59–85; V. I. Lenin, Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism (1916; repr., London: Penguin, 2010), 67–92.

[58] General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885).

[59] Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa, 253-261.

[60] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: 1876–1912 (New York: Random House, 1991), 253–261.

[61] Martin Chanock, Law, Custom and Social Order: The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985), 60–65.

[62] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: 1876–1912 (New York: Random House, 1991), 253–261.

[63] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 203–205.

[64] John Iliffe, Africans: The History of a Continent, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017), 203–205.

[65] Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 221-232.

Bibliography:

Baikie, William Balfour. Narrative of an Exploring Voyage up the Rivers Kwóra and Bínue (Niger and Tsádda) in 1854–1856. London: John Murray, 1856.

Cain, P. J., and A. G. Hopkins. British Imperialism, 1688–2000. London: Longman, 2001.

Chakrabarty, Dipesh. Provincializing Europe: Postcolonial Thought and Historical Difference. Princeton, NJ: Princeton University Press, 2000.

Chanock, Martin. Law, Custom and Social Order: The Colonial Experience in Malawi and Zambia. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1985.

Chinweizu. The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers, and the African Elite. New York: Random House, 1975.

Crais, Clifton. The Making of the Colonial Order: White Supremacy and Black Resistance in the Eastern Cape, 1770–1865. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1992.

Curtin, Philip D. Death by Migration: Europe’s Encounter with the Tropical World in the Nineteenth Century. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1989.

Curtin, Philip D. The Image of Africa: British Ideas and Action, 1780–1850. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1964.

Davidson, Basil. Africa in History: Themes and Outlines. Rev. ed. New York: Touchstone, 1995.

Frankema, Ewout, Jeffrey G. Williamson, and Pieter Woltjer. “An Economic Rationale for the African Scramble: The Commercial Transition and the Commodity Price Boom of 1845–1885.” NBER Working Paper No. 21213 (2015).

Headrick, Daniel R. The Tools of Empire: Technology and European Imperialism in the Nineteenth Century. New York: Oxford University Press, 1981.

Hobson, J. A. Imperialism: A Study. London: George Allen & Unwin, 1902.

Iliffe, John. Africans: The History of a Continent. 3rd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2017.

International Court of Justice. Western Sahara (Advisory Opinion). 1975.

Keith, Arthur Berriedale. The Belgian Congo and the Berlin Act. Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1919.

Kiple, Kenneth F., ed. The Cambridge World History of Human Disease. New York: Cambridge University Press, 1993.

Lenin, V. I. Imperialism, the Highest Stage of Capitalism. 1916. Reprint, London: Penguin, 2010.

Livingstone, David. Narrative of an Expedition to the Zambesi and Its Tributaries, and of the Discovery of the Lakes Shirwa and Nyassa, 1858–1864. London: John Murray, 1865.

McCracken, John. Politics and Christianity in Malawi, 1875–1940: The Impact of the Livingstonia Mission in the Northern Province. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1977.

Moir, Frederick L. M. After Livingstone: An African Trade Romance. London: Hodder and Stoughton, 1923.

Moore, Sir William. “On the Feasibility of Acclimatization in Tropical Africa.” Journal of the Royal United Service Institution 35, no. 159 (1891): 477–492.

Pakenham, Thomas. The Scramble for Africa: 1876–1912. New York: Random House, 1991.

Prestholdt, Jeremy. Domesticating the World: African Consumerism and the Genealogies of Globalization. Berkeley: University of California Press, 2008.

Rodney, Walter. How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. Rev. ed. London: Verso, 2018.

Rubenson, Sven. The Survival of Ethiopian Independence. London: Heinemann, 1976.

Rubenson, Sven. “The Protectorate Paragraph of the Wichale Treaty.” Journal of African History 5, no. 2 (1964): 243–283.

Sheriff, Abdul. Slaves, Spices and Ivory in Zanzibar: Integration of an East African Commercial Empire into the World Economy, 1770–1873. London: James Currey, 1987.

Smuts, Jan Christiaan. Jan Christian Smuts: A Biography. London: Cassell, 1952.

Spear, Thomas. “Neo-Traditionalism and the Limits of Invention in British Colonial Africa.” Journal of African History 44, no. 1 (2003): 3–27.

Stanley, Henry Morton. Through the Dark Continent; or, The Sources of the Nile Around the Great Lakes of Equatorial Africa and Down the Livingstone River to the Atlantic Ocean. 2 vols. London: Sampson Low, Marston, Searle & Rivington, 1878.

Temperley, Howard. “The British and American Anti-Slavery Expeditions to the Niger in the Nineteenth Century.” Journal of African History 6, no. 1 (1965): 123–129.

Thornton, John K. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. 2nd ed. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

Thornton, John K. The Kingdom of Kongo: Civil War and Transition, 1641–1718. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1983.

Thornton, John K. “Early Portuguese Expansion in West Africa: Its Nature and Consequences.” In Portugal, the Pathfinder: Journeys from the Medieval toward the Modern World, edited by George D. Winius, 121–132. Madison: Hispanic Seminary of Medieval Studies, 1995.

United Nations General Assembly. Resolution (30th Session). United Nations Official Documents (UN.org).

Zewde, Bahru. A History of Modern Ethiopia, 1855–1991. 2nd ed. Athens, OH: Ohio University Press, 2001.

Berlin Conference. General Act of the Berlin Conference on West Africa. 1885.

A Publication by EzroniX,

Paper written and researched by; Emmer Atwiine

Edited by; Ezron Kaijuka