The Scramble and Partition of Africa Explained

The Scramble and Partition of Africa Explained!

The Drawing of Lines That Still Bleed

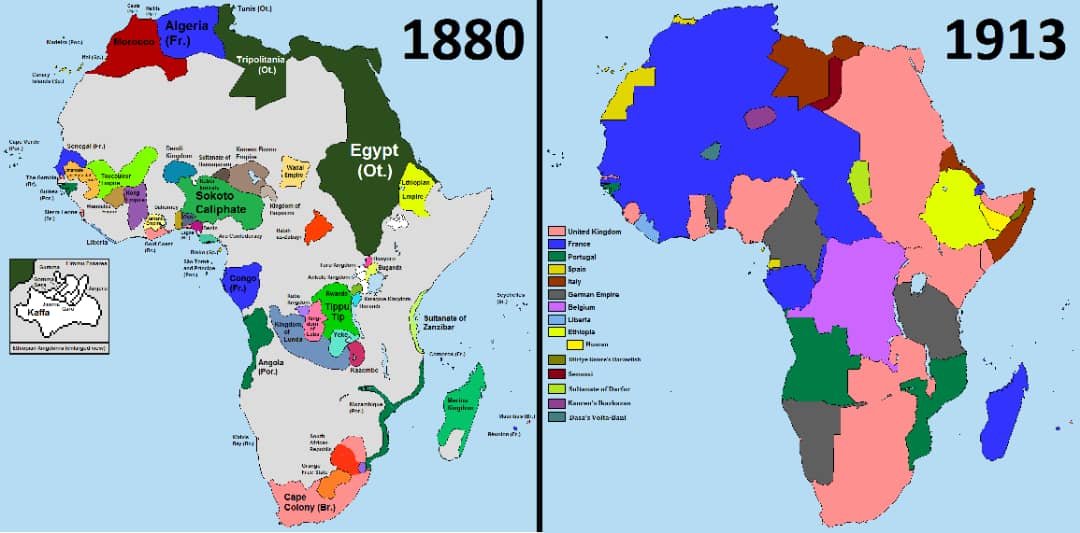

Map Africa in 1880 vs. Africa in 1913

In 1880, the vast interior of Africa was a tapestry of independent kingdoms, empires, and communities—largely unknown to the outside world. By 1914, nearly the entire continent was shaded in the colors of European empires. This frantic, transformative period is known as the Scramble for Africa. It was a land grab of unprecedented scale and speed—a story of greed, rivalry, and technological might that would fundamentally reshape the destiny of the African continent. As historian Thomas Pakenham so vividly describes it, the Scramble was “a gigantic, fateful lottery,” one whose winning tickets were drawn in European capitals and whose consequences are still being felt today.[1]

Our journey will follow the arc of the Scramble, from its deep-rooted causes to its enduring legacy. We will move beyond simple explanations to explore the complex interplay of economics, politics, and ideology that propelled European powers inland. We will sit in on the conference where they divided the continent without consulting its people, analyze the methods they used to enforce their rule, and honor the fierce resistance of African societies. Finally, we will see how the arbitrary lines drawn on maps—and witness how those same lines, once drawn in arrogance, still bleed into the present— in the 19th century continue to influence the politics, conflicts, and identities of modern Africa.

1. The Starting Gun: What Was the Scramble and What Triggered the Sudden Rush?

Between 1881 and 1914, Europe carved up Africa with breathtaking speed and ambition—a race that would redraw the map of the African continent. The Scramble for Africa was the invasion, occupation, division, and colonization of the African continent by seven Western European powers in a remarkably short period, approximately between 1881 and 1914. The key players were Great Britain, France, Germany, Belgium, Italy, Portugal, and Spain. To understand why this rush happened so suddenly after centuries of limited coastal contact, we must look at a combination of long-term pressures and immediate triggers.

For nearly four centuries, Europeans limited their presence in Africa to the coasts. They built forts and trading posts for gold, ivory, and, most tragically, human beings through the transatlantic slave trade. The interior remained terra incognita—a land Europeans saw as mysterious and perilous. Historian John Iliffe observes that while they lingered on the coast for centuries, their influence inland was minimal.[2]” Meanwhile, African empires like the Ashanti in the west and Swahili city-states in the east thrived under their own systems of rule.

Then why the sudden shift? The transition from this informal influence to a frantic race for formal ownership was triggered by a few key events in the early 1880s. The first was the ambitious project of one man: King Leopold II of Belgium who cloaked greed in the language of 'humanitarianism’. Frustrated that his small country had no empire, Leopold used the language of humanitarianism and science to mask a ruthless commercial venture. He hired the explorer Henry Morton Stanley to secure treaties with chiefs along the Congo River, effectively claiming a vast territory in the heart of Africa as his personal property. Historian Adam Hochschild documents, that while there were treaties most of these treaties were often signed under duress or through deliberate misunderstanding.[3] Leopold’s success showed that enormous wealth and prestige could be gained from the African interior, setting off alarm bells for other European powers.

The second major trigger was Britain's occupation of Egypt in 1882 marked another decisive moment. Britain intervened militarily to protect its financial interests, particularly the Suez Canal—the vital lifeline to its empire in India.

This action sent shockwaves through Europe. France, which had shared influence in Egypt, was outraged and humiliated. According to historians Ronald Robinson and John Gallagher, the occupation of Egypt was the "switch" that turned on the Scramble.[4] It deepened Anglo-French rivalry and drove France to aggressively expand its empire in West Africa as compensation.

As tensions between Britain and France grew, Germany seized the opportunity to assert itself as a new imperial power. In 1884, Chancellor Otto von Bismarck announced protectorates over Togo, Cameroon, and South-West Africa, formalizing the competition and creating further tension among western powers. According to historian H.L. Wesseling[5], Chancellor Otto von Bismarck’s move was a calculated response to European tensions, especially between Britain and France, as he sought to secure Germany’s status as a world power. Rivalry had now evolved into an all-out continental scramble. With that, it was a free-for-all, and no power could afford to be left out. This escalating competition would soon expose deeper motivations—economic ambitions, political rivalries, and ideological beliefs—that defined the next phase of the Scramble for Africa.

2. The Roots of the Rush: Historical Shifts and European Motivation

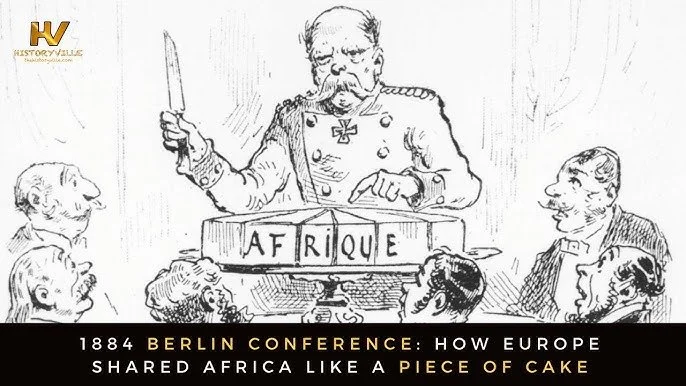

A 19th-century political cartoon depicting European nations dividing the "African cake"

In the wake of intensifying European rivalries and diplomatic maneuvering, while the triggers were immediate, the underlying causes of the Scramble had been simmering for decades, creating a fertile ground for imperial expansion.

The Industrial Revolution and Resource Needs

The Industrial Revolution not only transformed economies but reshaped lives—it filled cities with smoke that stirred new ambitions and created an insatiable hunger for progress that demanded resources beyond Europe’s shores. The Industrial Revolution, which began in Britain in the late 18th century, fundamentally altered Europe's relationship with the world. Factories demanded a constant supply of raw materials. Initially, palm oil was crucial for lubricating machinery. Later, the demand for rubber for tires and electrical insulation, copper for wiring, and gold and diamonds for wealth and luxury became insatiable. Africa was perceived as a vast, untapped reservoir of these resources. Furthermore, as European nations industrialized, they needed new markets for their manufactured goods. According to economic historians P.J. Cain and A.G. Hopkins, British expansion was heavily driven by "gentlemanly capitalists"—financiers in the City of London—who sought new, secure fields for investment.[6] Colonies offered both guaranteed sources of raw materials and captive markets, a powerful economic combination.

Bridging Economic Ambition and Political Rivalry: Competition Among European Nations

The political landscape of Europe after the Franco-Prussian War (1870-71) was tense and competitive. The unification of Germany under Bismarck had upset the old balance of power. As noted by historian H.L. Wesseling, colonial possessions became a new arena for this rivalry, a way for nations to assert their prestige and power without direct conflict on the European continent.[7] For France, humiliated by its defeat, building a vast overseas empire became a project of national rejuvenation. For the newly unified nations of Germany and Italy, acquiring a "place in the sun" was a symbol of being a great power. This nationalist rivalry created a dangerous domino effect; when one power moved to claim a territory, the others felt compelled to do the same to prevent being strategically encircled or economically shut out.

The Roles of Explorers, Missionaries, and Imperial Ideologies

The journey into the African interior was paved by explorers and missionaries. Figures like David Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley not only stirred public imagination but influenced policymakers and investors, whose enthusiasm for discovery soon transformed into imperial ambition. Livingstone and Henry Morton Stanley captured the European public's imagination with their tales of vast lakes, mighty rivers, and unknown peoples. Their maps, published in newspapers and books, replaced blank spaces with potential wealth, making the continent seem knowable and claimable.

Missionaries followed the explorers, seeking to spread Christianity and end the internal African slave trade. While many were driven by genuine humanitarian zeal, their presence often had unintended consequences. Their appeals for protection from local resistance provided European governments with a moral pretext for military intervention and annexation.

This was all framed by a powerful ideological justification. Yet beneath the lofty words lay a contradiction—the so‑called mission to 'civilize' masked the greed and cruelty of conquest. The hypocrisy of these claims made the ideology itself a tool of domination, the concept of the "White Man's Burden," popularized by Rudyard Kipling. This ideology portrayed imperialism as a noble, self-sacrificing duty to "civilize" the so-called "backward" peoples of the world. It was bolstered by pseudo-scientific racism and Social Darwinism, which argued that the white race was biologically and culturally superior and thus destined to rule over others. As powerfully argued by the scholar Chinweizu, this was a convenient fiction. He writes that it provided a "veneer of morality" used to mask the brutal realities of exploitation and plunder.[8] It allowed Europeans to view conquest not as theft, but as a charitable obligation.

3. Carving the Cake: The Berlin Conference and the Partition of Africa

The Berlin Conference of 1884-85, showing European diplomats around a table

With tensions rising over competing claims—a culmination of years of economic rivalry, Germany’s growing colonial assertiveness, and Leopold’s aggressive Congo ventures— in Central Africa, particularly between Leopold's International African Association and the French, German Chancellor Otto von Bismarck convened an international conference in Berlin from November 1884 to February 1885. The attendees were the key European powers—Austria-Hungary, Belgium, Britain, France, Germany, Italy, Portugal, Russia, Spain, and the Ottoman Empire—along with the United States. The most glaring absence was that of any African leadership. The fate of the continent was being decided by outsiders in a European capital.

In the cold Berlin winter, beneath the glow of chandeliers and the hum of diplomatic conversation, delegates gathered in rooms heavy with cigar smoke and ambition. The primary objective, as recorded in the General Act of the Berlin Conference[9], was to regulate European colonization and trade in Africa "in order to avert the dangers which might result from the rivalries of the various nationalities." In essence, they were meeting to ensure their scramble for Africa did not lead to a wider war in Europe. It was about managing their own competition, not about the well-being of Africans.

The General Act and "Effective Occupation"

The key outcome, as detailed by historians Thomas Pakenham[10] and H.L. Wesseling[11], was the General Act of the Berlin Conference. Its most significant principle was that of "effective occupation." This meant that a European power could not just claim a territory based on a coastal outpost or an explorer's flag-planting ceremony. To have their claim recognized by other powers, they had to demonstrate actual administrative control on the ground—show that they could maintain order, enforce laws, and have a visible presence. This rule, intended to prevent conflict, ironically triggered a mad dash inland. To prove "effective occupation," European agents raced to sign treaties with local leaders and establish military forts before their rivals could.

How African Borders Were Drawn

The drawing of Africa's borders, as explored by scholars like A. Adu Boahen[12] and Matthew Ghobrial[13], who highlight the deep cultural and social consequences of these arbitrary divisions, was an act of breathtaking geographical and cultural arrogance. The lines were drawn with rulers and pencils on maps in European chancelleries, paying no heed to the human landscape. As noted by historian Basil Davidson, these "frontiers were drawn with a ruler on a map, not with any knowledge of or concern for the peoples living there."[14]

The Lasting Impact of the Arbitrary Borders

Divided Peoples: As noted by Jeffrey Herbst[15], these arbitrary colonial borders split cohesive ethnic and linguistic groups, hindering the development of strong centralized states after independence. Herbst emphasizes how this fragmentation weakened political cohesion across the continent. The Somali nation, for example, was partitioned among British Somaliland, Italian Somaliland, French Djibouti, and British Kenya (and later Ethiopian empire). The Ewe people were divided between German Togoland and the British Gold Coast. The consequences of this arbitrary division were profound and are still felt today.

Forced Unions: Mahmood Mamdani[16] highlights that these same borders forced historical rivals and culturally distinct societies into artificial unions, creating governance crises that persist to this day. His analysis shows how colonial boundaries entrenched ethnic divisions and shaped the political instability of many postcolonial states. Conversely, historical rivals and vastly different societies were forced together within single administrative units. In Nigeria, hundreds of distinct ethnic groups, including the Hausa-Fulani in the north and the Yoruba and Igbo in the south, were amalgamated into one colony, creating a recipe for future internal conflict.

The Berlin Conference did not partition the entire continent—the Scramble continued for years afterward—but it provided the legal framework and the momentum for the final division. It was the moment the 'rules of the game' were set, a game in which Africans had no say. The decisions made in those smoke-filled halls cast long shadows—lines drawn not only on maps but across generations. This moral cost would echo in the struggles of governance and identity that followed, setting the stage for how control was imposed in the next phase of Africa’s story. Scramble continued for years afterward—but it provided the legal framework and the momentum for the final division. It was the moment the "rules of the game" were set, a game in which Africans had no say.

4. Methods of Empire

Before delving into the distinct methods used by colonial powers, it is important to note the moral and logistical challenges they faced in transforming imperial ambition into tangible control—an endeavor marked by both administrative ingenuity and profound human cost.

How European Powers Established Control

The European powers did not simply draw lines on a map; they had to establish physical control over the territories they claimed. The methods they used varied, reflecting their national philosophies, the resources they were willing to commit, and the nature of the resistance they encountered.

A photo of a British colonial officer with a local chief to illustrate Indirect Rule

British Indirect Rule

This model of governance later shaped administrative practices in postcolonial Africa, influencing patterns of authority and local governance, as discussed by Mahmood Mamdani[17] and Toyin Falola[18], who link the colonial legacy of indirect rule to enduring political centralization and social stratification.

The British often preferred a system of indirect rule, particularly in densely populated areas with established hierarchies. Perfected by Lord Lugard in Northern Nigeria, this system involved governing through existing African rulers and institutions. The British would appoint a "Native Authority," often a traditional chief, to collect taxes, maintain order, and implement colonial directives. This system was cost-effective, as it required fewer British administrators, and it minimized direct confrontation by co-opting the traditional elite. However, it had major drawbacks. It often froze traditional societies in time, giving unchecked power to conservative chiefs and stifling the emergence of a modern educated elite. It also entrenched ethnic identities, as the system was based on the idea of "tribal" units. As noted by historian A.H.M. Kirk-Greene[19], indirect rule was less about partnership and more about control, with the appearance of collaboration masking deep inequalities of power.

French Assimilation and Direct Rule

As noted by historian Raymond Betts[20], the policy of assimilation was more rhetorical than practical, with France's proclaimed ideals of equality seldom realized in practice.

Their approach was fundamentally different. They pursued a policy of assimilation and direct rule. The ideal was to transform African subjects into "black Frenchmen," imbued with French language, culture, and values. Their system was highly centralized, run by French officials from Paris and Dakar, and aimed to break down traditional power structures. The famous Four Communes of Senegal, whose inhabitants could elect a deputy to the French parliament, were the model. While this system could offer a path to French citizenship for a small elite, it was also more disruptive and culturally destructive, seeking to replace African identities with a French one. As historian Alice Conklin[21] observes, the rhetoric of assimilation often concealed coercion and exclusion, as the promise of equality was limited to a select few.

Other Colonial Powers

Portugal maintained a claim to its old coastal territories but exerted little control inland until the Scramble forced its hand. Its rule was characterized by harsh forced labor systems and a rigid, racially stratified society.

Germany acquired a significant empire but ruled with notable brutality. In German South-West Africa (Namibia), they committed the first genocide of the 20th century against the Herero and Nama peoples, driving them into the desert to die of thirst and starvation. As documented by historian Jeremy Sarkin[22], the German military systematically exterminated entire communities through massacres, concentration camps, and forced labor. This is further supported by historians Jan-Bart Gewald[23] and David Olusoga[24], who asserted that the brutality of German rule in Namibia reflected an ideology of racial extermination and settler dominance, offering broader context to the atrocities that unfolded.

King Leopold II of Belgium stands in a category of his own. He ruled the Congo Free State not as a Belgian colony, but as his personal property. His regime, focused on the maximum extraction of wild rubber, instituted a system of terror. A report by British diplomat Roger Casement detailed the "wholesale slaughter and misery" inflicted upon the Congolese, including forced labor, mass killings, and the notorious practice of cutting off the hands of those who failed to meet rubber quotas.[25] International outrage eventually forced the Belgian government to take the colony away from Leopold in 1908.

Methods of Conquest: Treaties, Force, and Deception

These methods of empire, while effective in securing control, came at a staggering human cost—lives lost, cultures disrupted, and societies reshaped by violence and coercion. This moral reckoning forms the shadow that lingers over the colonial narrative, leading directly into the story of resistance that followed.

The initial conquest was achieved through a mix of diplomacy and violence.

Treaties: European agents fanned out across the interior, signing hundreds of treaties with local leaders. As noted in the writings of Chinweizu, these agreements were often profoundly unequal; signed with X's by leaders who did not understand the concept of ceding sovereignty permanently or signed under the threat of force.[26] They provided the legal fig leaf for the land grabs ratified in Europe.

Force: Where treaties failed or were deemed unnecessary, the Europeans used overwhelming force. The single greatest advantage was technological. The invention of the Maxim gun, the world's first fully automatic machine gun, allowed tiny European-led forces to defeat much larger African armies. As the poet Hilaire Belloc cynically wrote, "Whatever happens, we have got / The Maxim gun, and they have not."[27] Advances in medicine, particularly the use of quinine to treat the deadly malaria, also gave Europeans a fighting chance.

5. Resistance and Consequences: The African Response and its Legacy

Samori Touré, the Mandinka resistance leader - Image by anonymous.

Where force and deception defined imperial control, resistance defined the African response.

The narrative of the Scramble is not one of passive African surrender. From the moment European forces moved inland, they met with determined, sophisticated, and often prolonged resistance. This resistance took many forms, from full-scale military confrontation to everyday acts of cultural and economic defiance.

Violent and Diplomatic Resistance

Across the continent, African leaders and societies fought back with incredible bravery.

Samori Touré and the Mandinka Empire (West Africa): One of the most formidable leaders, Samori Touré built a powerful Islamic state and equipped his army with modern rifles. For nearly two decades (1882–1898), he waged an effective guerrilla war against French forces, using scorched-earth tactics and diplomatic maneuvering. As historian Yves Person[28] notes, Touré’s resistance exemplified the adaptability and strategic intelligence of African leadership during this period.

The Zulu Kingdom (Southern Africa): Under King Cetshwayo, the Zulu army famously defeated the British at the Battle of Isandlwana in 1879, one of the worst defeats in British colonial history. Though ultimately defeated later that year, their resistance became a powerful symbol of African military prowess.

The Mahdist State (Sudan): In 1881, a religious leader known as the Mahdi declared a jihad against Egyptian (and by extension, British) rule. His followers captured Khartoum in 1885, killing General Charles Gordon and establishing an Islamic state that endured until 1898. This movement, as analyzed by P.M. Holt[29], demonstrated how religious and nationalist sentiment merged into potent anti-colonial resistance.

The Asante Empire (West Africa): The Asante fought a series of wars against the British throughout the 19th century. Their final conflict, the War of the Golden Stool (1900), was led by Queen Mother Yaa Asantewaa, who rallied her people to defend their sovereignty. As T.C. McCaskie[30] explains, this resistance reflected both political defiance and deep cultural symbolism, as the Golden Stool represented the soul of the Asante nation.

Ethiopia’s Victory at Adwa (East Africa): Ethiopia stands as the great exception to colonial conquest. Under Emperor Menelik II, the Ethiopian army defeated Italian forces at the Battle of Adwa in 1896—a monumental victory that preserved Ethiopian independence and inspired pan-African pride. Historian Raymond Jonas[31] calls Adwa “a triumph of diplomacy, intelligence, and faith,” underscoring its enduring importance as a symbol of African resilience.

In addition to these well-known cases, resistance movements in North and Central Africa also stood out for their tenacity and scale. The Maji Maji Rebellion (1905–1907) in German East Africa, as described by historian John Iliffe[32], united diverse ethnic groups against colonial oppression through shared spiritual conviction, though it was met with brutal suppression. Similarly, early Algerian uprisings, later chronicled by Charles-Robert Ageron[33], demonstrated how North African populations resisted both militarily and culturally, foreshadowing the long struggle for decolonization.

Immediate and Long-Term Impacts

Even in defeat, these acts of resistance left lasting intellectual and moral legacies that inspired later independence movements, bridging the struggle for survival with the dawn of liberation.

The conquest, once complete, had devastating consequences for African societies. Indigenous systems of governance were dismantled, economies reoriented toward European needs, as cultural identities were suppressed or reshaped.

On Political Systems: Colonial authorities systematically removed kings and chiefs who resisted European control, replacing them with compliant figures. Traditional decision-making structures were supplanted by centralized colonial administrations. As Ali Mazrui[34] observes, this destruction of indigenous political systems severed the historical continuity of African governance.

On Economies: Colonial economies were reoriented entirely toward the extraction of raw materials for Europe. Subsistence farming was often replaced by cash-crop plantations (e.g., cocoa, cotton), making local populations vulnerable to shifts in global commodity prices. Infrastructure—railways, roads, ports—was built not to connect African communities, but to funnel resources from the interior to the coast for export. As historian Walter Rodney powerfully argued in his seminal work, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, the colonial system was designed not to develop Africa for Africans, but to exploit it for the benefit of Europe, creating a structural dependency that crippled long-term growth.[35]

Cultural and Psychological Effects: Beyond material exploitation, colonialism inflicted a profound cultural and psychological toll. The denigration of African belief systems, languages, and institutions fostered a legacy of inferiority. Frantz Fanon[36] powerfully articulated this in The Wretched of the Earth, describing the psychological violence of colonization that alienated Africans from their identity and heritage.

Seeds for Future Liberation

Ironically, colonialism also planted the seeds of its own undoing. The imposition of European education and ideas introduced Africans to concepts of liberty, equality, and nationalism. Educated elites began to use these same ideas to challenge imperial authority. Pan-African thinkers and activists like Edward Blyden, J.E. Casely Hayford, and later Kwame Nkrumah drew inspiration from both African traditions and Western ideals to demand self-determination.

As historian Toyin Falola[37] notes, this awakening marked the genesis of African nationalism—a convergence of pride, pain, and purpose that would define the 20th century. The memory of resistance, from Samori Touré to Adwa, became the moral and symbolic foundation for modern independence movements.

This intellectual awakening soon evolved into organized activism, exemplified by the early Pan-African conferences such as the 1900 London Conference, where African and diaspora leaders gathered to articulate a shared vision of self-determination and racial unity.

6. The Enduring Legacy: How the Scramble Shapes Africa Today

As the fires of resistance dimmed and independence dawned, Africa carried not only new hopes but also the heavy burdens of its colonial inheritance.

How the Scramble Shapes Africa Today

The Scramble for Africa did not end with independence in the 1950s and 1960s. Its legacy remains woven into the fabric of modern Africa, influencing borders, governance, economies, and identities. The lines drawn in European capitals during the late 19th century continue to shape the continent’s political realities and social struggles in the 21st century.

The Persistence of Arbitrary Borders

The most visible legacy of the Scramble for Africa is the map itself—a cartographic testament to 19th-century imperial ambition, where the boundary lines drawn in 1885 can still be traced almost perfectly onto modern maps of Africa. When African nations gained independence, they largely inherited the colonial borders created in the 1880s and 1890s. The Organization of African Unity (OAU), founded in 1963, made the pivotal decision to uphold these colonial boundaries under the principle of uti possidetis juris, fearing that attempts to redraw them along ethnic or historical lines would unleash endless conflict. As historian Basil Davidson[38] observed, these boundaries, drawn without consideration for Africa’s cultural and ethnic diversity, locked the continent into an artificial geopolitical framework that still defines it today.

The result has been persistent internal tensions and cross-border disputes. Nations such as Nigeria, Sudan, and the Democratic Republic of Congo illustrate how colonial boundaries forced diverse groups into single political entities, creating structural instability that postcolonial governments have struggled to overcome.

African Modern-Day Conflicts with Roots in the Scramble

Many of Africa's most intractable conflicts can trace their roots directly to the arbitrary divisions and administrative policies of the colonial era.

The Nigeria-Biafra War (1967-1970): Rooted in ethnic and regional tensions intensified by British indirect rule, this civil war claimed more than a million lives. As historian Elizabeth Isichei[39] notes, the Biafran tragedy exposed the deep fractures left by colonial amalgamation and highlighted the challenge of building unity in diversity.

The Rwandan Genocide (1994): Belgian colonial policy institutionalized ethnic divisions by favoring the Tutsi minority over the Hutu majority. This system of racialized identity laid the groundwork for resentment and violence that culminated in genocide. Historian Gérard Prunier[40] emphasizes that colonial ethnography transformed flexible social categories into rigid, destructive hierarchies.

The Conflict in the Democratic Republic of Congo (DRC): The DRC’s history of instability and conflict is deeply rooted in its colonial past under King Leopold II. Its immense mineral wealth, once exploited through forced labor, continues to attract foreign interference and internal strife. Historian Crawford Young³⁹ argues that Leopold’s extractive legacy created a state designed for plunder rather than governance—a structure that persists in new forms today.

Horn of Africa Instability: The Horn of Africa also bears visible scars of colonial legacy. Somalia’s fragmented state and Eritrea’s long struggle for independence from Ethiopia both reflect the disruptive boundaries imposed by European powers and later Cold War rivalries.

Governance and Identity

As scholars Achille Mbembe[41] and Frederick Cooper[42] have argued, the postcolonial state in Africa evolved through a complex dialogue between inherited colonial governance models and new aspirations for sovereignty, blending continuity with transformation.

Colonial administrative systems left deep imprints on post-independence governance. The centralized bureaucracies established by European powers encouraged authoritarianism and a winner-takes-all approach to politics. As Mahmood Mamdani[43] contends, colonial rule divided Africans into racialized citizens and ethnicized subjects, laying the foundations for modern governance crises. The legacy of indirect and direct rule continues to influence political structures and identity politics across the continent.

Yet, not all legacies of the colonial era are purely negative. The shared experience of colonialism and the collective struggle for independence fostered a sense of continental unity that gave rise to Pan-Africanism. Leaders like Kwame Nkrumah, Julius Nyerere, and Haile Selassie envisioned a united Africa capable of transcending colonial divisions. As P. Olisanwuche Esedebe[44] writes, Pan-Africanism became both a political ideology and a moral compass, urging Africans to reclaim agency over their destiny.

The Long Shadow of Berlin; Enduring Lessons and Reflections

The story of the Scramble for Africa is not confined to the past; it is a living history. Its legacies—visible in Africa’s borders, economies, and governance—remain cautionary lessons about power, greed, and resilience. The arbitrary lines drawn in 1885 continue to shape not only Africa’s challenges but also its aspirations for unity and progress. As historian Ali Mazrui[45] reflected, the task for modern Africa is not merely to erase the marks of colonialism, but to transform them into foundations for renewal and self-determination.

The Scramble for Africa was more than a geopolitical event—it was a human tragedy and a turning point in world history. The decisions made in the grand halls of Europe between 1884 and 1885 redrew not only the map of Africa but also the moral landscape of the modern world. The Berlin Conference and its aftermath institutionalized a global order built on domination and exploitation, where power was measured not by justice but by the ability to conquer and divide.

From the Congo Basin to the Horn of Africa, the marks of that partition are still visible today—in borders that ignore nations, in conflicts that echo colonial divides, and in the psychological scars of displacement and inequality. As historian Thomas Pakenham[46] wrote, "the partition of Africa was the most comprehensive and the most formalized division of territory in history, achieved with the least regard for the people whose lands were divided."

Yet Africa’s story does not end with victimhood. Out of the violence of conquest arose the courage of resistance. Out of the chains of subjugation came the will to reclaim freedom. From the partition came unity, from humiliation, pride. The voices of leaders, thinkers, and artists from across the continent have transformed the memory of conquest into a philosophy of renewal. As Chinua Achebe[47] reflected, the African narrative is one of endurance and creation, a refusal to be defined by pain alone.

End Notes:

[1] [Pakenham, Thomas, “The Scramble for Africa: 1876-1912”, 1991, Page xxi.]

[2] [Iliffe, John, “Africans: The History of a Continent”, 1995, Page 193.]

[3] [Hochschild, Adam, “King Leopold's Ghost: A Story of Greed, Terror, and Heroism in Colonial Africa”, 1998, Page 58.]

[4] [Robinson, Ronald and Gallagher, John, “Africa and the Victorians: The Official Mind of Imperialism”, 1961, Page 465.]

[5] H.L. Wesseling, Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880–1914 (Praeger, 1996)

[6] [Cain, P.J. and Hopkins, A.G., “British Imperialism: Innovation and Expansion, 1688-1914”, 1993, Page 365.]

[7] [Wesseling, H.L., “Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880-1914”, 1996, Page 110.]

[8] [Chinweizu, “The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers and the African Elite”, 1975, Page 45.]

[9] General Act of the Berlin Conference (1885), Article VI; in General Act of the Conference of Berlin, signed 26 February 1885.

[10] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: The White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (New York: Random House, 1991). (1885), Article VI; in General Act of the Conference of Berlin, signed 26 February 1885.

[11] Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880-1914

[12] A. Adu Boahen, African Perspectives on Colonialism (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 45–47.

[13] Matthew Ghobrial, The Colonial Map and the Invention of Boundaries in Africa (London: Routledge, 2004), 112–115.

[14] [Davidson, Basil, “The Black Man's Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State”, 1992, Page 86.]

[15] Jeffrey Herbst, States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 2000), 73–75.

[16] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 21–23

[17] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 37–40.

[18] Toyin Falola, Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria (Bloomington: Indiana University Press, 2009), 15–18.

[19] A.H.M. Kirk-Greene, Indirect Rule: The Nigerian Experience (London: Cass, 1965), 22–24.

[20] Raymond F. Betts, Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914 (New York: Columbia University Press, 1961), 89–91.

[21] Alice Conklin, A Mission to Civilize: The Republican Idea of Empire in France and West Africa, 1895–1930 (Stanford: Stanford University Press, 1997), 54–58.

[22] Jeremy Sarkin, Germany’s Genocide of the Herero: Kaiser Wilhelm II, His General, His Settlers, His Soldiers (Cape Town: UCT Press, 2011), 102–104.

[23] Jan-Bart Gewald, Herero Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia, 1890–1923 (Oxford: James Currey, 1999), 134–137.

[24] David Olusoga and Casper W. Erichsen, The Kaiser's Holocaust: Germany's Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism (London: Faber & Faber, 2010), 85–88.

[25] [Casement, Roger, “The Casement Report”, 1904, Page 15.]

[26] [Chinweizu, “The West and the Rest of Us”, 1975, Page 112.]

[27] [Belloc, Hilaire, “The Modern Traveller”, 1898.]

[28] Yves Person, Samori: Une révolution Dyula (Dakar: IFAN, 1968), 210–214.

[29] P.M. Holt, The Mahdist State in the Sudan, 1881–1898 (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1958), 133–136.

[30] T.C. McCaskie, State and Society in Pre-Colonial Asante (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995), 298–301.

[31] Raymond Jonas, The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2011), 242–245.

[32] John Iliffe, A Modern History of Tanganyika (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1979), 180–184.

[33] Charles-Robert Ageron, Modern Algeria: A History from 1830 to the Present (Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press, 1991), 56–59.

[34] Ali A. Mazrui, Cultural Forces in World Politics (Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann, 1990), 112–114.

[35] [Rodney, Walter, “How Europe Underdeveloped Africa”, 1972, Page 149.]

[36] Frantz Fanon, The Wretched of the Earth (New York: Grove Press, 1963), 42–44.

[37] Toyin Falola, Nationalism and African Intellectuals (Rochester, NY: University of Rochester Press, 2001), 89–92.

[38] Basil Davidson, The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State (New York: Times Books, 1992), 153–156.

[39] Elizabeth Isichei, A History of Nigeria (London: Longman, 1983), 322–325.

[40] Crawford Young, The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective (New Haven: Yale University Press, 1994), 77–80.

[41] Achille Mbembe, On the Postcolony (Berkeley: University of California Press, 2001), 72–75.

[42] Frederick Cooper, Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), 18–21.

[43] Mahmood Mamdani, Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism (Princeton: Princeton University Press, 1996), 289–292.

[44] P. Olisanwuche Esedebe, Pan-Africanism: The Idea and Movement, 1776–1991 (Washington, DC: Howard University Press, 1994), 165–168.

[45] Ali A. Mazrui, The Africans: A Triple Heritage (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1986), 401–404.

[46] Thomas Pakenham, The Scramble for Africa: The White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912 (New York: Random House, 1991), 673–676.

[47] Chinua Achebe, Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays (New York: Doubleday, 1988), 141–144.

REFERENCES

1. Thomas Pakenham (1991). The Scramble for Africa: The White Man’s Conquest of the Dark Continent from 1876 to 1912. New York: Random House.

2. H.L. Wesseling (1996). Divide and Rule: The Partition of Africa, 1880–1914. Westport, CT: Praeger.

3. Basil Davidson (1992). The Black Man’s Burden: Africa and the Curse of the Nation-State. New York: Times Books.

4. A. Adu Boahen (1987). African Perspectives on Colonialism. Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press.

5. Matthew Ghobrial (2004). The Colonial Map and the Invention of Boundaries in Africa. London: Routledge.

6. Jeffrey Herbst (2000). States and Power in Africa: Comparative Lessons in Authority and Control. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

7. Mahmood Mamdani (1996). Citizen and Subject: Contemporary Africa and the Legacy of Late Colonialism. Princeton: Princeton University Press.

8. Toyin Falola (2009). Colonialism and Violence in Nigeria. Bloomington: Indiana University Press.

9. Raymond F. Betts (1961). Assimilation and Association in French Colonial Theory, 1890–1914. New York: Columbia University Press.

10. Jan-Bart Gewald (1999). Herero Heroes: A Socio-Political History of the Herero of Namibia, 1890–1923. Oxford: James Currey.

11. David Olusoga & Casper W. Erichsen (2010). The Kaiser’s Holocaust: Germany’s Forgotten Genocide and the Colonial Roots of Nazism. London: Faber & Faber.

12. John Iliffe (1979). A Modern History of Tanganyika. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

13. Charles-Robert Ageron (1991). Modern Algeria: A History from 1830 to the Present. Trenton, NJ: Africa World Press.

14. Achille Mbembe (2001). On the Postcolony. Berkeley: University of California Press.

15. Frederick Cooper (2002). Africa Since 1940: The Past of the Present. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

16. Yves Person (1968). Samori: Une révolution Dyula. Dakar: IFAN.

17. P.M. Holt (1958). The Mahdist State in the Sudan, 1881–1898. Oxford: Clarendon Press.

18. T.C. McCaskie (1995). State and Society in Pre-Colonial Asante. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

19. Raymond Jonas (2011). The Battle of Adwa: African Victory in the Age of Empire. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

20. Ali A. Mazrui (1990). Cultural Forces in World Politics. Portsmouth, NH: Heinemann.

21. Walter Rodney (1972). How Europe Underdeveloped Africa. London: Bogle-L’Ouverture Publications.

22. Frantz Fanon (1963). The Wretched of the Earth. New York: Grove Press.

23. P. Olisanwuche Esedebe (1994). Pan-Africanism: The Idea and Movement, 1776–1991. Washington, DC: Howard University Press.

24. Elizabeth Isichei (1983). A History of Nigeria. London: Longman.

25. Gérard Prunier (1995). The Rwanda Crisis: History of a Genocide. London: Hurst & Co.

26. Crawford Young (1994). The African Colonial State in Comparative Perspective. New Haven: Yale University Press.

27. Roger Casement (1904). The Casement Report (British Parliamentary Papers). London: HMSO.

28. Jeremy Sarkin (2011). Germany’s Genocide of the Herero: Kaiser Wilhelm II, His General, His Settlers, His Soldiers. Cape Town: UCT Press.

29. Chinweizu (1975). The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers and the African Elite. New York: Vintage Books.

30. Ngũgĩ wa Thiong’o (1986). Decolonising the Mind: The Politics of Language in African Literature. Nairobi: East African Educational Publishers.

31. Ali A. Mazrui (1986). The Africans: A Triple Heritage. Boston: Little, Brown and Company.

32. Achille Mbembe (2021). Out of the Dark Night: Essays on Decolonization. New York: Columbia University Press.

33. Chinua Achebe (1988). Hopes and Impediments: Selected Essays. New York: Doubleday.

A Publication by EzroniX, Paper written by Emmer Atwiine edited by Ezron R. Kaijuka.