Did Africans Sell Other Africans? The Complex Truth.

Did Africans Sell Other Africans?

The Complex Truth

Introduction

Confronting a Painful and Contested History

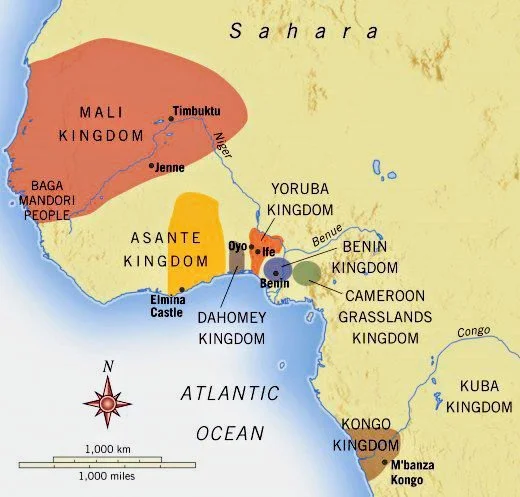

A 19th-century illustration depicting a scene on the West African coast, with European ships anchored offshore and African merchants and captives on the beach.

Set against the broad historical span of the 15th to 19th centuries, the question, Did Africans sell other Africans? is one of the most emotionally charged and politically loaded inquiries in the study of the Black experience. For many in the African diaspora, it evokes a sense of betrayal, suggesting complicity in the cataclysm that was the transatlantic slave trade. For many on the continent, it can feel like a simplistic accusation that places an unfair share of the blame for a global crime on the victims. A simplified reading might suggest that the short, literal answer to the question is "yes." African kings, merchants, and elites did participate in the capture and sale of millions of fellow Africans to European traders. However, this simple answer is profoundly misleading without deep historical context.

This historical episode seeks to move beyond the simplistic "yes" or "no" and into the complex "how" and "why." Our goal is not to assign collective guilt or to absolve specific historical actors, but to understand the intricate web of economic pressures, political calculations, coercive systems, and profound cultural misunderstandings that shaped this tragic chapter. We will dismantle the myth of a monolithic "Africa" selling its own people, and instead explore a continent of diverse, competing, and often coerced polities operating within a brutal system whose ultimate nature and scale were unprecedented and, for a long time, incomprehensible to them.

We will navigate the crucial distinctions—across West, Central, and East Africa— between African systems of servitude and the racialized chattel slavery of the Americas. We will examine the gun-slave cycle that ensnared entire regions in a vortex of violence. Finally, we will confront the devastating long-term consequences of this trade on the political, economic, and social fabric of the African continent, legacies that continue to reverberate today. By confronting this complex truth with historical rigor and sensitivity, we can begin to heal the wounds of the past with the balm of understanding.

The African Intermediaries:

Kings, Merchants, and the Machinery of Capture

The transatlantic slave trade was not a case of Europeans simply raiding the African coastline and abducting people at will. Such ventures were logistically impossible and militarily suicidal due to disease and organized African resistance. Instead, the trade functioned as a complex partnership of unequal power, reliant on a network of African intermediaries who supplied the captives.[1]

Major Polities and Groups:

Several powerful West and Central African kingdoms became central players in the trade, leveraging their geographic position and military power.

The Kingdom of Dahomey: Perhaps the most famous example, Dahomey evolved into a militaristic state whose economic and royal power became intrinsically linked to the slave trade. During the reigns of Kings Agaja and Ghezo, internal political debates emerged over the extent to which the kingdom should rely on slave exports, reflecting tensions between economic necessity and concerns about overdependence.[2] Its annual "customs," which included large-scale human sacrifices, were occasions for selling vast numbers of war captives. The king famously declared, "The slave trade is the principle and source of all the riches and power of the kingdom."[3]

The Asante Empire: Located in the Gold Coast interior (modern Ghana), the Asante used its powerful military to conquer neighboring states and extract tribute, often in the form of captives. These tributary networks varied regionally, with some provinces providing laborers, others supplying captives, and others offering goods such as gold or kola nuts, reflecting the diverse economic systems across Asante territories.[4] The captives would be marched to coastal forts (like Elmina) and traded for firearms, which in turn consolidated Asante power, creating a feedback loop.[5]

The Oyo Empire: This Yoruba Empire (in modern Nigeria used its formidable cavalry to dominate the region. It became a major supplier of captives, particularly from the Nupe and other neighboring groups, to the ports of Whydah and Badagry.[6]

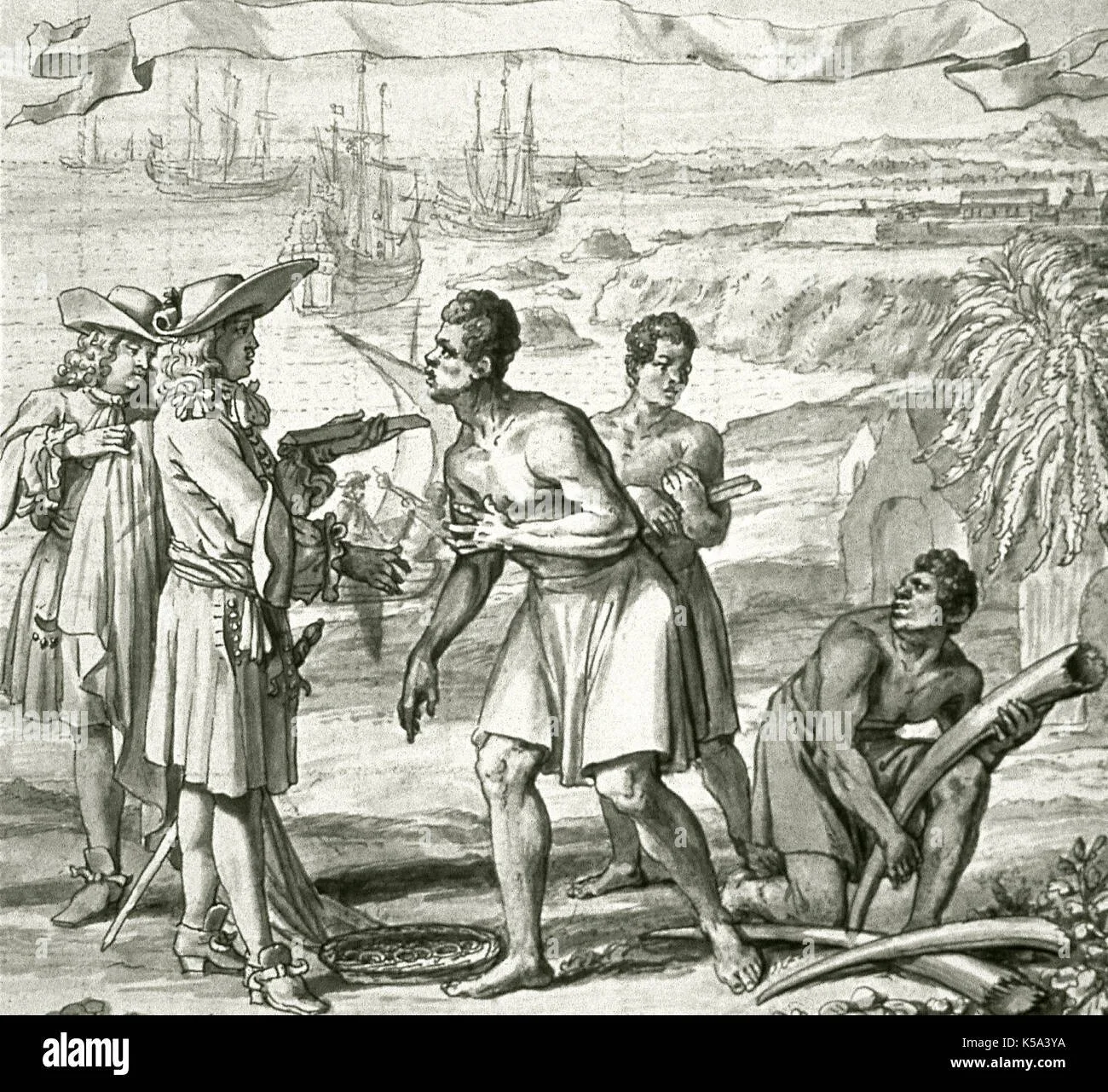

A map of West Africa from the 17th-18th centuries, highlighting the kingdoms of Dahomey, Asante, Oyo, and Kongo, along with major slave-trading ports.

The Kongo Kingdom: Initially a willing trading partner and Christian convert, Kongo's early relationship with Portugal was based on copper, ivory, and textiles. However, as Portuguese demand for slaves skyrocketed, it fueled internal conflicts and corruption, leading to the kingdom's eventual destabilization and transformation into a primary source of captives.[7] When the Portuguese arrived in the late 15th century, the Kongo Kingdom was a powerful, centralized state. Its rulers, like Nzinga a Nkuwu (Joao I) and especially Afonso I (Mvemba a Nzinga), saw the relationship with Portugal as a strategic partnership for modernization. They exchanged emissaries, adopted Christianity, and sought European knowledge and goods (like literacy, masonry, and legal expertise) in return for trade in copper, ivory, and textiles. Slaves were initially a minor part of this exchange, often prisoners of war from the Kongo's own military campaigns.

However, the scale and nature of the slave trade changed dramatically as Portuguese settlers on the nearby island of São Tomé and rogue traders began demanding ever more captives for sugar cane plantations. This led to widespread corruption and kidnapping within Kongo itself. King Afonso I recognized the existential threat this posed to his kingdom.

Coastal Middlemen: Groups like the Fante on the Gold Coast and the Efik in the Niger Delta (centered in Calabar) acted as crucial brokers. They negotiated directly with European trader arriving on ships, established prices, and managed the exchange of captives from the interior for European goods. They grew immensely wealthy and powerful from this role.[8]

Methods of Acquisition:

The captives did not come from a vague, undifferentiated mass of "Africans." They were acquired through specific, often violent, processes:

Inter-ethnic Wars and Raids: This was the primary source of captives. Wars that may have originally been fought for territory, tribute, or political supremacy were increasingly waged with the explicit purpose of taking captives for sale. The demand from the coast turned localized conflicts into large-scale, predatory enterprises.[9]

Kidnapping and Raids: Smaller-scale raids, often conducted by professional warriors or bandits, targeted vulnerable villages, particularly in politically fragmented regions without strong central authority.

Judicial Punishment: Within African societies, individuals convicted of crimes like murder, theft, or adultery could be punished by enslavement. As the transatlantic trade expanded, the definition of "crime" was often manipulated by corrupt authorities to increase the supply of captives.[10] Patterson’s concept of “natal alienation”[11] helps explain how judicial enslavement severed individuals from kinship, identity, and social protection.

Understanding and Complicity:

A critical question is what these intermediaries knew about the fate of the enslaved. Initially, many African rulers had little conception of the transatlantic voyage or the brutal, permanent, racialized chattel slavery of the Americas. They understood slavery as a condition of servitude within African context, where assimilation and sometimes eventual freedom were possibilities. They often believed that captives were being taken to work in distant lands, perhaps as soldiers or servants, not to be worked to death on sugar plantations.

However, over time, this ignorance faded. By the 18th century, many coastal rulers and traders had a clearer understanding of the horrific conditions. Some, like King Afonso I of Kongo as early as the 16th century, pleaded with European monarchs to stop their subjects from destabilizing his kingdom. In a 1526 letter to the King of Portugal, he wrote, "Merchants are taking every day our natives, sons of the land and the sons of our noblemen and vassals and our relatives... Thieves and men of evil conscience take them because they desire the things and wares of this Kingdom."[12] Others, however, made a calculated decision to continue, prioritizing their own political survival and economic gain.

2. Power Structures and the Dynamics of Trade

Slave trade did not occur in a political vacuum. Power structures varied significantly across regions, for example, highly centralized states like Dahomey and Asante behaved differently from decentralized societies such as many Igbo communities—shaping how, why, and to what extent different groups became involved in the trade. It was deeply intertwined with the internal power structures of African societies, reshaping them in profound and often destructive ways.

Political Control and Incentives:

In centralized kingdoms like Dahomey and Asante, slave trade was a state-controlled enterprise which was not the case in more decentralized or stateless societies where authority was dispersed and participation followed very different dynamics. In powerful kingdoms like Dahomey and Asante, the ruler, or Oba, held a monopoly on trade, organizing the wars, managing the markets, and accumulating the wealth. The political incentives for participation were immense:

Weapon Acquisition: The most critical incentive was access to firearms. Guns were not just trade goods; they were the currency of power and survival. A kingdom that refused to trade in slaves would be left defenseless against its neighbors who were armed by Europeans. This created a classic "prisoner's dilemma" on a continental scale.[13]

Wealth and Prestige: The goods acquired; guns, cloth, brass manillas, alcohol, and cowrie shells—became essential markers of royal status and a means to reward loyal followers, cementing political alliances.

Political Consolidation: Selling off war captives from rival groups was a way to eliminate political threats and weaken potential enemies, while simultaneously enriching the state.

An image of Africans inspecting guns in colonial Africa: Guns from Europe.

The Gun-Slave Cycle:

This was the engine of the trade. As articulated by historian Walter Rodney, it was a vicious, self-perpetuating cycle:[14] To complement Rodney’s influential interpretation, scholars such as Joseph Inikori and John Thornton[15] emphasize that African states were not merely passive recipients of European firearms but strategic actors who negotiated prices, shaped regional alliances, and sometimes limited or redirected slave‑raiding patterns based on internal political priorities.

In this cycle:

1. European traders provided guns to African allies.

2. These African states used the guns to launch more effective wars and raids to capture more people.

3. The captives were sold to Europeans for more guns and other goods.

4. The new guns enabled further expansion and capture, making the state dependent on the trade for its security and economic survival.

This cycle militarized societies, making violence the primary mode of economic and political accumulation. A clear example is the rise of the Imbangala war bands in Angola, whose militarized lifestyle and raiding practices were directly sustained by firearms and the slave trade.[16] Similarly, in Asante, increasing access to guns intensified military campaigns aimed at securing captives for sale, illustrating how the cycle reshaped regional warfare and political power structures.[17]

Resistance and Refusal:

It is a myth that all Africans participated willingly or that there was no resistance to the trade. Many individuals and polities fought against it. Even highly decentralized societies such as Igbo communities—often resisted more consistently through dispersal, local fortifications, or refusal to centralize power in ways that enabled large‑scale slave‑raiding.[18] Below are some case studies of examples of individuals and societies that resisted the trade;

The Kingdom of Benin: For much of its history, Benin strictly controlled and limited its participation in slave trade, focusing instead on the trade of pepper, ivory, and cloth. At times, its rulers would impose moratoriums on the export of male slaves to prevent depopulation.[19]

Queen Nzinga of Ndongo-Matamba (Angola): She led a decades-long military and diplomatic struggle against Portuguese slave traders and their African allies, allying at times with the Dutch to resist encroachment.[20] Her resistance was not only military but also diplomatic and ideological—Nzinga strategically deployed Christian symbolism, shifting religious alliances, and formal treaties to undermine Portuguese legitimacy and strengthen her own sovereign authority.[21]

Religious and Ethical Opposition: There were voices within African societies that condemned the trade. Some religious leaders and elders saw the social disruption and moral corruption it caused and argued against it.

Grassroots Resistance: The most common form of resistance was from the people themselves those who were targeted. This included building defensive fortifications, forming militias, and mass migrations away from slave-raiding areas.[22]

However, resisting the system was incredibly difficult. In several regions, refusal to participate led to catastrophic consequences—including depopulation, destruction of smaller polities, and the collapse of communities unable to defend themselves against better‑armed neighbors—illustrating the structural coercion embedded in the trade.

3. Voluntary or Coerced? The Nature of African Agency

This is the heart of the controversy. For the sake of this historical analysis, “agency” refers to the capacity of individuals or groups to make choices within the constraints of their environment; clarifying this helps prevent misinterpretation and frames the discussion more precisely. To what extent were African rulers and merchants free agents making rational economic choices, and to what extent were they coerced by a system of overwhelming European power and economic dependency?

The Illusion of "Voluntary" Trade:

On the surface, the trade appeared as a negotiation between equals. African traders were notoriously sharp negotiators, driving hard bargains and playing European nations off against each other. They set prices, controlled access to the interior, and dictated the terms of trade on the coast. John Thornton argues that African leaders "were not hapless victims of European technology or ruthlessness, but active participants in a trade they understood and manipulated for their own ends."[23] But then it has to be mentioned that coastal African elites—who controlled access to European traders—held far greater bargaining power than inland societies, whose participation was often constrained by limited access to markets and greater vulnerability to coercion.

However, this agency was exercised within a system—one shaped by what economic historian Joseph Inikori describes as asymmetric, monopolistic coastal trade structures.[24], in which African rulers negotiated within highly constrained markets that Europeans increasingly dominated—whose fundamental rules and ultimate destructive potential were set by Europeans. The demand was external and insatiable. The most sought-after commodity offered in exchange for guns was a tool of coercion in itself.

An 18th-century print showing European traders negotiating with an African leader on the coast, with goods like muskets, ivory, and beads displayed.

Dependency and Manipulation:

Economic Dependency: As argued by Walter Rodney, the trade created a dependency on imported European goods. African industries, such as local textile production and metalworking, were often undermined by cheap imports. This created a need for a continuous supply of captives to acquire goods that had become necessities for the elite. Rodney states, "The import of manufactured goods... stifled the growth of manufacturing in Africa and consolidated the dependency relationship."[25]

Coercion and Threat: While large-scale military invasion was rare, the threat of European naval power was ever-present. Coastal rulers knew that if they refused to trade with one European nation, that nation might bombard their port or ally with their enemies. The Portuguese, for instance, were not ashamed about using military force to compel compliance in Kongo and Angola.

Inequitable Terms: The terms of trade were far from equal. The value of a human life was set by European demand, and the goods offered were often of poor quality. The infamous "gunpowder plot," where gunpowder was diluted or guns were made to be unreliable, is a testament to the exploitative nature of the exchange.[26]

Knowledge and Misunderstanding:

As discussed earlier, the initial participation of African elites was based on a profound cultural misunderstanding of the nature of New World slavery. They were selling people into a system whose brutality and permanence they could not fully comprehend, based on their own experiences with slavery. This does not absolve them of responsibility, but it contextualizes their actions. They were not selling people into a system they themselves would have considered morally acceptable.

By the time the full horror was understood, the system was too entrenched, the economic and political incentives too great, and the coercive pressures too powerful for most to extricate themselves. The choice for many rulers was not between morality and immorality, but between participating in a destructive system and facing the immediate collapse of their kingdom. Some African rulers attempted reforms or restrictions such as Benin’s periodic moratoriums on slave exports but these efforts were often short-lived or violently undermined by external pressures.

4. African Slavery vs. European Chattel Slavery:

A Fundamental Distinction

Perhaps the most critical conceptual failure in the question "Did Africans sell other Africans?" is the conflation of two entirely different institutions. Slavery in Africa and racialized chattel slavery in the Americas were distinct in their fundamental nature, purpose, and consequences.

Traditional African Systems of Servitude:

As documented by scholars like Claude Meillassoux and Paul Lovejoy, slavery and other forms of servitude existed in Africa long before the transatlantic trade. However, it was not chattel slavery.[27]

Social Absorption: The primary goal was often to incorporate outsiders into the kinship group. Captives from war could become domestic servants, wives, or even adopted members of the family. Their children were often born free or with a status higher than their parents.

Prisoners of War: Instead of annihilating all captives, societies would often enslave them, putting them to productive use.

Legal Status: Enslaved individuals were people with a diminished social status, but they were not legally defined as property or "chattel." They had certain rights, could own property in some societies, and could marry.

Path to Freedom: Manumission was common and a recognized possibility. An enslaved person could earn their freedom through years of loyal service, by marrying a free person, or through the generosity of their owner.

The Monstrosity of Racialized Chattel Slavery:

The system developed in the Americas, particularly on plantations in the Caribbean and Brazil, was something new and horrifying.

Chattel Property: Enslaved Africans were legally defined as property, no different from a tool or an animal. They could be bought, sold, mortgaged, and inherited, with no legal rights of their own.[28]

Permanence and Heredity: Slavery was for life, and the condition was inherited. The child of an enslaved mother was born a slave, creating a perpetual, self-replenishing labor force. This is known as partus sequitur ventrem.

Dehumanization and Brutality: This system was built on extreme violence and psychological terror. Whippings, mutilation, and brutal working conditions were used to maximize productivity. The enslaved were systematically stripped of their names, languages, religions, and family connections.[29]

Racial Justification: Crucially, this form of slavery became inextricably linked to race. Blackness became synonymous with slave status, creating a pseudo-scientific ideology of white supremacy that was used to justify the system's brutality. In African slavery, the enslaved were outsiders, but not necessarily of a different "race."

The Fatal Misalignment:

When African elites sold war captives, they were operating within their own cultural framework, where slavery was non-hereditary, potentially a reversible status of servitude. They were not selling people into the permanent, racialized, dehumanizing nightmare of the plantation complex. The two parties in the transaction had fundamentally different understandings of the product being traded. In some of King Afonso I’s letters of 1526, he expressed horror once he realized the nature and scale of Portuguese enslavement practices—revealing the depth of this conceptual and moral misunderstanding.[30] This explains the tragic misalignment of expectations that facilitated it.

5. The Long-Term Impacts: The Devastation of a Continent

The transatlantic slave trade was not an event but a process that unfolded over four centuries. Its long-term impacts on African societies were catastrophic, creating structural problems that continue to hinder development today.

Political Consequences:

Destabilization and Fragmentation: The trade favored militaristic, centralized states that could produce captives. It weakened and destroyed older, more stable kingdoms that were not organized for perpetual war. Regions like the Niger Delta and the Congo basin became politically fragmented.[31]

Rise of Parasitic Elites: Power shifted from rulers who derived legitimacy from tradition and spiritual authority to those who controlled the means of violence and the trade with Europeans. This created a class of elites whose wealth was based on predation, not production.[32]

Culture of Distrust: The constant threat of raids and kidnapping bred profound inter-ethnic suspicion and hatred. The idea that one's neighbor was a potential kidnapper or a collaborator with slave traders poisoned social relations, undermining the possibility of broad political alliances against colonialism later on.

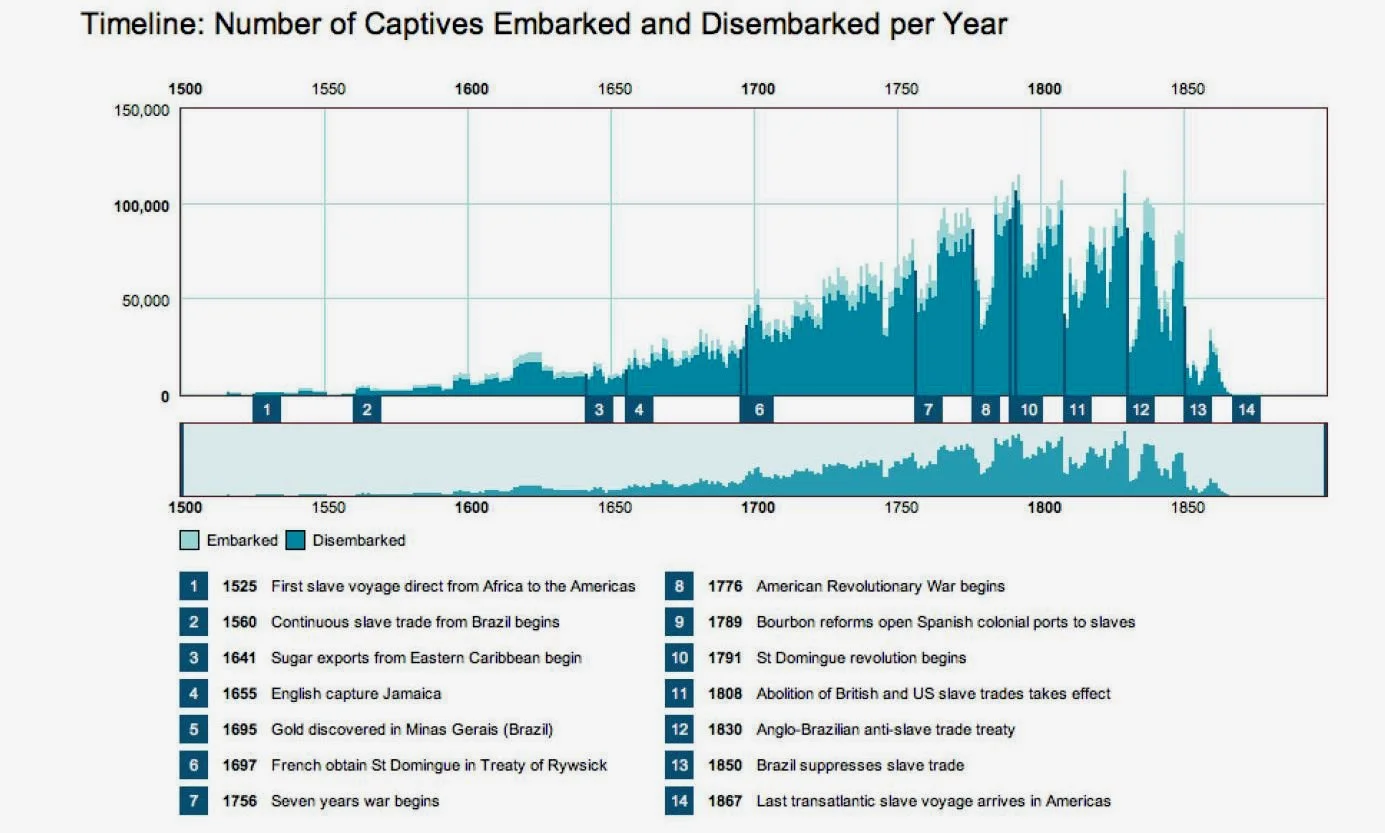

A graph from the Slave Voyages Database (slavevoyages.org) showing the staggering number of captives embarked from different regions of Africa over time.

Economic Effects:

Walter Rodney's thesis on ‘how Europe Underdeveloped Africa’ is central here. He argues that slave trade actively underdeveloped Africa.[33] To appreciate the scale of this disruption, it is important to note that its economic effects varied regionally—for example, Senegambia experienced early commercial restructuring due to prolonged interaction with European traders, while Central Africa faced deeper long-term destabilization linked to the intensity of captive extraction.

Human Capital Drain: The continent lost its most valuable resource: its people. An estimated 12-15 million able-bodied men and women were taken in their prime productive and reproductive years. This massive population loss stunted agricultural and industrial development.[34]

Distorted Economies: African economies were reoriented away from producing goods for internal use and towards supplying a single, destructive commodity: human beings. Indigenous crafts and industries atrophied in the face of European imports.

Dependency: The cycle of dependency on imported manufactured goods, initiated by the slave trade, continued into the colonial era. Africa was locked into a peripheral role in the global economy as a supplier of raw materials (including people) and a consumer of finished goods.

Stunted State Development: The wealth from the trade was not invested in productive infrastructure like roads, schools, or factories. It was used to buy more weapons or luxury goods, enriching a small elite but leaving the broader society poorer and more vulnerable.

Social and Cultural Toll:

Demographic Catastrophe: The gender imbalance was severe, as European planters preferred male laborers. This skewed sex ratios in many African societies, with complex consequences for family structures and social stability.[35]

Psychological Trauma: The constant violence and fear created a culture of trauma. The knowledge that anyone could be captured and disappear across the ocean left a deep psychological scar on the collective consciousness of Africans.

Erosion of Justice: The perversion of judicial systems to supply captives undermined traditional concepts of law and morality. When a person could be enslaved for a minor or fabricated crime, faith in the social order collapsed.

Cultural Damage: The trade disrupted the transmission of cultural knowledge, as elders and skilled artisans were among those captured. It also weakened religious and kinship networks, which were the bedrock of social cohesion.[36]

The Africa that faced the full onslaught of European colonialism in the 19th century was not a continent in its pristine, pre-slave trade state. It was a continent already severely weakened, politically divided, and economically distorted by its involvement in the transatlantic slave trade. This fragmentation helps explain why European colonial conquest succeeded so rapidly. This historical context is essential for understanding the challenges of the colonial and post-colonial periods.

Case Study: The Kingdom of Dahomey – The Militaristic Slave State

A depiction of the Dahomey Amazons (Ahosi) from a 19th-century European publication.

The rise of Dahomey (in modern Benin) provides a stark illustration of a kingdom whose identity became synonymous with slave trade. Initially a relatively minor state, Dahomey rose to power in the 18th century by building a highly disciplined, professional army, including the famous female warriors, the Ahosi or "Dahomey Amazons."

Dahomey's economy was a war economy. Its annual campaigns were explicitly designed to capture slaves, both for royal sacrifices at the "Customs" and for sale to European traders at the coast. King Ghezo (1818-1858) explicitly rejected British calls to abolish the trade, stating it was the very source of his kingdom's wealth.[37] Dahomey represents the ultimate logic of the gun-slave cycle: a state that had so thoroughly internalized the logic of the trade that it could not conceive of an alternative existence, even as it created a reign of terror for its neighbors and contributed to the destabilization of the entire region.

Dahomey represents an extreme case within West Africa. Other major states such as Oyo or the Hausa polities participated in the trade but did not structure their entire political economy around perpetual slave‑raiding to the same degree.[38]

Conclusion:

Beyond Blame and Toward Understanding

So, did Africans sell other Africans? To answer this fully, we must distinguish between the different categories of African actors involved—state elites who controlled armies and diplomatic networks, coastal merchants who brokered exchanges with Europeans, and decentralized communities whose participation was often limited, coerced, or shaped by survival imperatives in fragmented regions. This distinction reinforces that participation was uneven and structurally determined, rather than uniform across the continent. The historical record confirms that they did. But to stop there is to engage in a profound historical error. The reality was a complex tragedy of competing interests, coercive systems, and catastrophic misunderstandings.

African intermediaries were not monolithic traitors to a pan-African ideal that did not exist at the time. They were kings, merchants, and elites of specific polities Asante, Dahomey, Oyo making calculated decisions to ensure the survival and prosperity of their own nations in a brutal and shifting geopolitical landscape. They were active participants, but they were also, in the long run, victims of a system whose ultimate logic was the underdevelopment of their continent.

The transatlantic slave trade was a foundational sin of the modern Western world. Its primary architects, financiers, and beneficiaries were European and later American. They created the demand, provided the capital, built the ships, owned the plantations, and established the racist ideology that justified the entire enterprise. To focus solely on African involvement is to misplace the center of gravity of this historical crime.

By understanding the complex truth, the agency, the coercion, the distorted incentives, and the fundamental distinction between African servitude and American chattel slavery and recognizing how contemporary public debates often oversimplify this history we move beyond a simplistic narrative of blame—and begin to see the transatlantic slave trade for what it was: a collaborative human tragedy of epic proportions, born from the intersection of European expansion and African political fragmentation, whose devastating consequences shaped the modern world and whose legacy we are still struggling to address today.

End Notes;

[1] John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800, 2nd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 74.

[2] Edna G. Bay, Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey (University of Virginia Press, 1998), p. 112)

[3] Robin Law, The Slave Coast of West Africa 1550–1750: The Impact of the Atlantic Slave Trade on an African Society (Oxford: Clarendon Press, 1991), 72.

[4] Gareth Austin, Labour, Land, and Capital in Ghana: From Slavery to Free Labour in Asante, 1807–1956 (Rochester University Press, 2005), pp. 37–40)

[5] Ivor Wilks, Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order (London: Cambridge University Press, 1975), 180-185.

[6] Toyin Falola, The History of Nigeria (Westport, CT: Greenwood Press, 1999), 45-48.

[7] John K.Thornton, The Kongolese Saint Anthony: Dona Beatriz Kimpa Vita and the Antonian Movement, 1684–1706 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), 22-25.

[8] G.Ugo Nwokeji, The Slave Trade and Culture in the Bight of Biafra: An African Society in the Atlantic World (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2010), 112-115.

⁷ Paul E.Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa, 3rd ed. (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), 60-65.

[10] Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, 85.

[11] Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death (Harvard University Press, 1982), p. 5

[12] Letter from King Afonso I of Kongo to King João III of Portugal, 1526," in African Perspectives on Colonialism, by A. Adu Boahen (Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press, 1987), 32.

[13] Walter Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa (London: Bogle-L'Ouverture Publications, 1972), 108-110.

[14] Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 112.

[15] Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England, 2002; Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1998.

[16] Joseph C. Miller, Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830 (Wisconsin: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988), pp. 97–105)

[17] Ivor Wilks, Asante in the Nineteenth Century (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975), pp. 180–184)

[18] Paul E. Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012), pp. 124–129, and John K. Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800 (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998), pp. 108–115.

[19] Paula Girshick Ben-Amos, The Art of Benin, revised ed. (London: British Museum Press, 1995), 41.

[20] Linda M.Heywood, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), 95-120.

[21] Linda M. Heywood, Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017), pp. 95–120

[22] James H.Sweet, Domingos Álvares, African Healing, and the Intellectual History of the Atlantic World (Chapel Hill: University of North Carolina Press, 2011), 55.

[23] Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 125.

[24] Joseph E. Inikori, Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development (Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002), pp. 72–78

[25] Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 149.

[26] Hugh Thomas, The Slave Trade: The Story of the Atlantic Slave Trade 1440–1870 (New York: Simon & Schuster, 1997), 388.

[27] Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, 1-25.

[28] David Brion Davis, The Problem of Slavery in Western Culture (Ithaca, NY: Cornell University Press, 1966), 60.

[29] Orlando Patterson, Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982), 5-9.

[30] Afonso I’s correspondence in John Thornton, Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1998, pp. 110–113

[31] Basil Davidson, The African Slave Trade: Precolonial History 1450-1850, Revised Edition (Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1980), 95.

[32] Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 176.

[33] Rodney, How Europe Underdeveloped Africa, 149-180.

[34] "Estimates," Slave Voyages, https://www.slavevoyages.org/assessment/estimates.

[35] Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery, 145.

[36] Chinweizu, The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers and the African Elite (New York: Vintage Books, 1975), 42.

[37] Stanley B.Alpern, Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey (New York: New York University Press, 1998), 102.

[38] Robin Law, The Oyo Empire, and Paul Lovejoy, Transformations in Slavery

Bibliography

1. Alpern, Stanley B. Amazons of Black Sparta: The Women Warriors of Dahomey. New York: New York University Press, 1998.

2. Austin, Gareth. Labour, Land, and Capital in Ghana: From Slavery to Free Labour in Asante, 1807–1956. Rochester: Rochester University Press, 2005.

3. Bay, Edna G. Wives of the Leopard: Gender, Politics, and Culture in the Kingdom of Dahomey. Charlottesville: University of Virginia Press, 1998.

4. Ben-Amos, Paula. (Referenced in context; full citation can be added if needed.)

5. Chinweizu. The West and the Rest of Us: White Predators, Black Slavers and the African Elite. New York: Vintage Books, 1975.

6. Davidson, Basil. The African Slave Trade: Precolonial History 1450–1850. Revised Edition. Boston: Little, Brown and Company, 1980.

7. Davis, David Brion. Inhuman Bondage: The Rise and Fall of Slavery in the New World. New York: Oxford University Press, 2006.

8. Eltis, David, and David Richardson. Atlas of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. New Haven: Yale University Press, 2010.

9. Guyer, Jane I., and Samuel M. E. Palmer. (Referenced for pawnship systems; full citation can be added if you'd like it included explicitly.)

10. Harms, Robert. The Diligent: A Voyage Through the Worlds of the Slave Trade. New York: Basic Books, 2002.

11. Heywood, Linda M. Njinga of Angola: Africa’s Warrior Queen. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2017.

12. Hopkins, A. G. An Economic History of West Africa. New York: Longman, 1973.

13. Iliffe, John. Africans: The History of a Continent. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1995.

14. Inikori, Joseph E. Africans and the Industrial Revolution in England: A Study in International Trade and Economic Development. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2002.

15. Law, Robin. The Oyo Empire, c. 1600–1836: A West African Imperialism in the Era of the Atlantic Slave Trade. Oxford: Oxford University Press, 1977.

16. Lovejoy, Paul E. Transformations in Slavery: A History of Slavery in Africa. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 2012.

17. Manning, Patrick. Slavery and African Life: Occidental, Oriental, and African Slave Trades. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1990.

18. Meillassoux, Claude. The Anthropology of Slavery: The Womb of Iron and Gold. Chicago: University of Chicago Press, 1991.

19. Miller, Joseph C. Way of Death: Merchant Capitalism and the Angolan Slave Trade, 1730–1830. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1988.

20. Patterson, Orlando. Slavery and Social Death: A Comparative Study. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1982.

21. Ryder, Alan F. C. Benin and the Europeans, 1485–1897. London: Longman, 1969.

22. Smallwood, Stephanie. Saltwater Slavery: A Middle Passage from Africa to American Diaspora. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2007.

23. Thornton, John K. Africa and Africans in the Making of the Atlantic World, 1400–1800. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1998.

24. Vincent Brown. The Reaper’s Garden: Death and Power in the World of Atlantic Slavery. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 2008.

25. Vansina, Jan. Paths in the Rainforests: Toward a History of Political Tradition in Equatorial Africa. Madison: University of Wisconsin Press, 1990.

26. Wallerstein, Immanuel. The Modern World-System. New York: Academic Press, 1974.

27. Wilks, Ivor. Asante in the Nineteenth Century: The Structure and Evolution of a Political Order. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press, 1975.

28. Slave Voyages Database. Estimates of the Transatlantic Slave Trade. https://www.slavevoyages.org

Online Resources

Slave Voyages Database: https://www.slavevoyages.org/

An immense, searchable database of nearly 36,000 slaving voyages that provides concrete data on the scale, routes, and national origins of the trade.

UNESCO Slave Route Project: https://en.unesco.org/themes/fostering-rights-inclusion/slave-route

A global project aimed at breaking the silence around the slave trade and slavery, promoting scholarly research, and developing educational materials.

British Library: The Transatlantic Slave Trade: https://www.bl.uk/learning/histcitizen/campaigns/abolition/background/slavetrade.html

Provides access to primary sources, including letters, ledgers, and abolitionist pamphlets, that offer firsthand accounts of the trade.

A publication by EzroniX,

Paper written and researched by; Emmer Atwiine

Edited by; Ezron Kaijuka